It’s simply a “thing to wear.” When translated literally, the word “kimono” suggests something plain, something basic: a bare bones way to cover up the body. And in its most basic sense, it is, referring as it could to virtually any piece of clothing. But “kimono” refers most commonly to the wrapped-front garment that evolved from the kosode robe of the 17th century, and it’s anything but a mere raiment to keep out the elements. From the flowing sleeves of furisode to the multi-layered junihitoe of the Heian period, there are many different types and styles of kimono that each convey various seasons, occasions, formality levels and aesthetics. On top of that, there are different types of obi, undergarments and accessories that make each ensemble an intricate work of art. Indeed, Japan’s “thing to wear,” imbued with history as well as artistry, has become one of the most recognizable symbols of Japan and its traditional culture.

Since the Meiji era brought Western-style fashions to Japan, wearing kimono has become an increasingly rare activity, one that’s usually reserved for special occasions like Coming-of-Age Day, tea ceremonies, graduations and weddings. In fact, most Japanese people don’t know how to put on a kimono by themselves and instead defer to professionals. As a result, the wearing of kimono is like a dying art in some ways. Enthusiasts, however, are fighting to preserve the practice with modern trends — helped out by renewed interest from younger generations.

If you count yourself among the enthusiasts but are still a little unsure about the details, we’ve got you covered. What follows is our ultimate guide for the beginner kimono shopper.

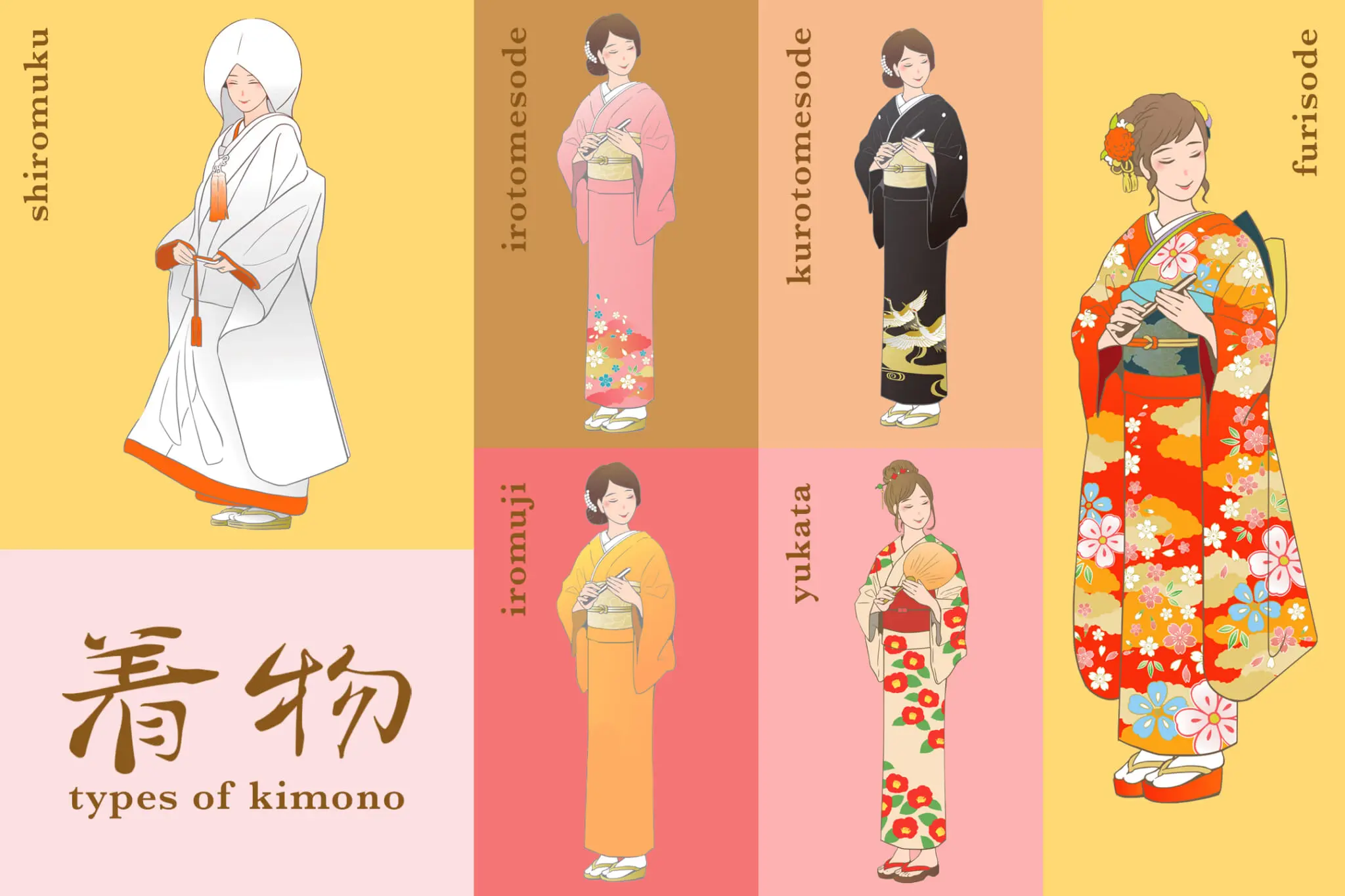

Types of Kimono

Formality

As previously mentioned, there are many types of kimono, some of which have a specific purpose. Within “purpose” is the idea of formality, an important consideration when choosing what to wear. Usually, the appropriate level can be determined by remembering that the primary figures of an event wear first-class formal attire (for example, the bride, groom and their parents), while guests wear second-class formal wear (semiformal attire). Let’s break down some of the most common types.

Komon

Casual, everyday wear. Komon are designed with a simple repeating pattern all over the fabric.

Iromuji

Informal to second-class formal wear. Iromuji translates to “plain color” (but does not include black kimono). These solid color kimono are very versatile. When iromuji are adorned with kamon or mon (family crests), their formality goes up.

Homongi

Second-class formal wear. Homongi translates to “visiting wear.” These semiformal kimono have overarching designs on the wearer’s left shoulder, hem and sleeves.

Irotomesode

Second-class to first-class formal wear. These kimono have designs only below the knees and are typically worn by married women. Irotomesode with five mon are considered first-class formal wear, whereas irotomesode with fewer mon are less formal.

Kurotomesode

First-class formal wear. The very formal kurotomesode are the black variants of the irotomesode and are worn by married women. These kimono have mon on both sides of the chest, the backs of the sleeves and the center of the back. You’ll commonly see the mother of the bride or groom wearing kurotomesode at weddings.

Furisode is commonly worn by girls during Coming of Age Day.

Furisode

First-class formal wear. Furisode, which translates to “swinging sleeves,” are easily identified by their extra-long sleeves. Within the furisode category , there are subcategories with varying sleeve lengths: ofurisode (about 104–120 cm), chufurisode (about 95–100 cm) and kofurisode (about 60–85 cm). They are typically worn by young, unmarried women, most often during their Coming-of-Age ceremony when they turn 20 years old (or 18, depending on the municipality).

Mofuku

First-class formal wear. Mofuku translates to “mourning clothes.” This solid-black kimono ensemble is only worn at funerals.

Shiromuku

First-class formal wear. This pure white kimono is worn by brides in traditional Japanese weddings, accompanied by a white hood called wataboshi or a tsunokakushi headdress. This style evolved from samurai weddings in the Edo era.

Yukata

Casual summer wear. Yukata — unlined cotton garments most commonly worn at summer festivals — find themselves at the bottom of the list for a likely unexpected reason: Despite looking, at a very basic level, quite similar to the kimono described above, yukata don’t share roots with them and are thus in a category of their own. Rather than the kosode of the 1600s, it was bathing that birthed yukata: Originally, they were worn as robes while hopping between hot springs. Some hotels and bathhouses still offer yukata for an authentic experience.

Yukata can be worn by both men and women, and is commonly seen at summer festivals.

Seasonal Construction

Formality isn’t the only way to categorize kimono; when it comes to construction, there are certain differences tied to season or, more recently, temperature that result in distinct types of kimono. These differences relate to fabric and lining.

Awase

Fall to spring (roughly October to May). Awase kimono are what you picture when you hear the word “kimono.” They’re worn for more of the year than the other kinds of seasonally constructed kimono, as, with their lining, they keep the wearer warm during the cooler months. Awase kimono have a more solid structure and, as a result, give the wearer a slightly different silhouette. When it comes to formal events, regardless of the time of year, awase kimono are the standard.

Hitoe

Cusp of summer and cusp of fall (roughly June and September). Hitoe are unlined kimono commonly worn during the transition from spring to summer and summer to fall. Traditionally, these periods correspond to June and September, months when it’s too hot for an awase kimono but not yet sweltering. With the onset of higher global temperatures, however, a bit of wiggle room has been introduced, and of course, there are regional differences relating to climate.

Usumono

Summer (roughly July and August). Like hitoe, usumono kimono are unlined. What sets them apart from hitoe is the fabric used to make them, which is thin, often of a loose, gauzy weave and semi-transparent. Fibers include silk, linen, hemp, cotton and polyester. The lightness of these kimono allows wearers to stay cool through the dog days of summer. Depending on the weave and fiber, there are even usumono considered appropriate for formal occasions. And, as usumono are see-through, they can be worn with a patterned nagajuban undergarment to fashionably show the layer underneath.

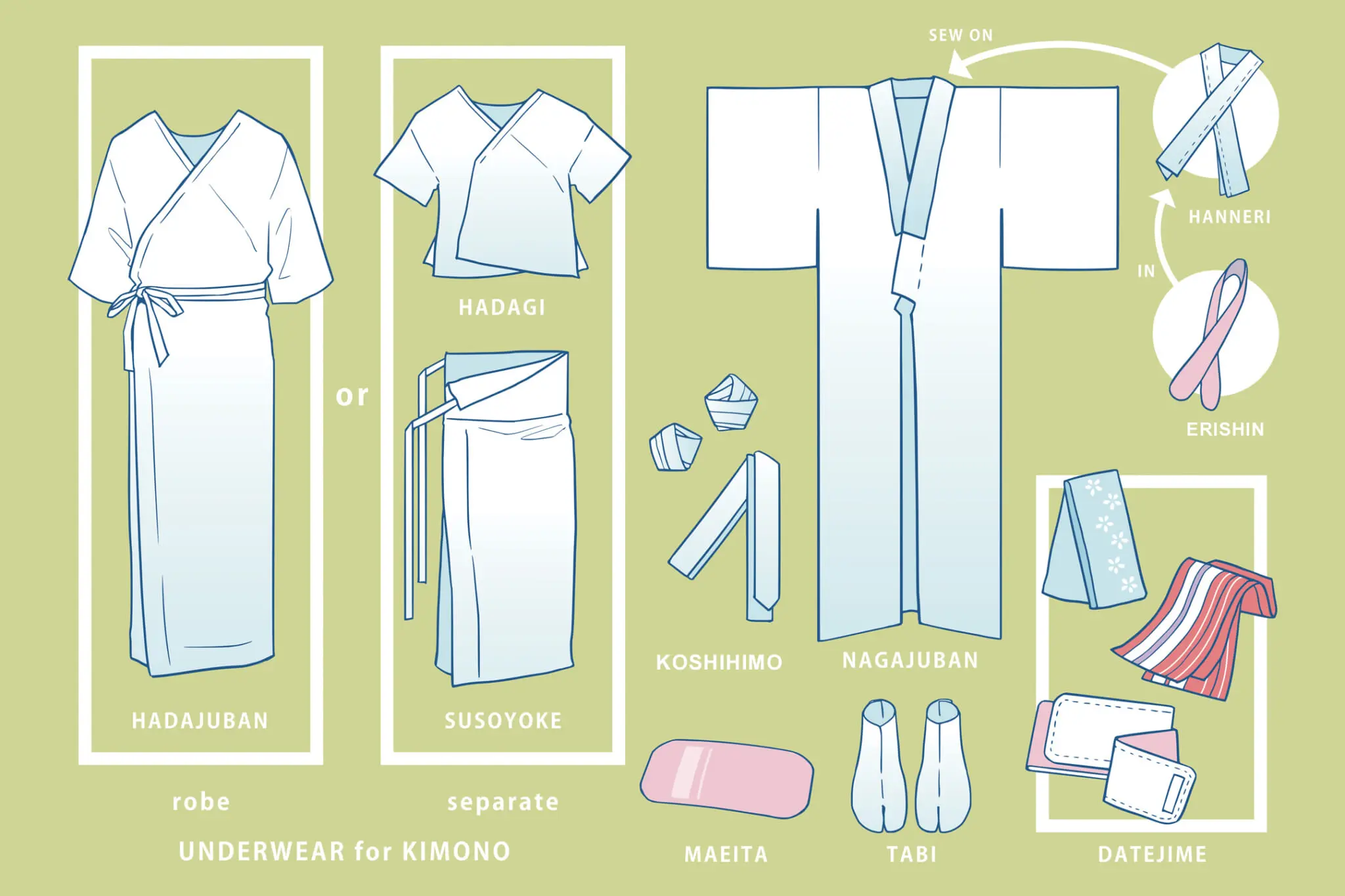

The Anatomy of a Kimono

While kimono may seem relatively straightforward upon initial glance, first-time wearers are quick to notice the many layers and ties that pull the look together. Kitsuke — the process of dressing in a kimono — takes dedication and practice. After all, there are no zippers or buttons to hold up the garment.

The first layer is the hadagi undergarment or a slip dress. The hadagi is a lightweight undergarment made from breathable materials like cotton. It absorbs sweat to prevent staining on the actual kimono and can be washed after every use. Tabi split-toe socks are worn with zori sandals.

Another undergarment, the nagajuban, is layered on top. Like the hadagi, the nagajuban’s purpose is to add a protective layer between the body and kimono to prevent any staining from sweat, oil or makeup. The nagajuban is made of silk or synthetic material and has sleeves like a kimono. A long plastic strip called erishin is inserted into the nagajuban collar to keep it stiffened in the correct shape. A decorative haneri can be sewn on the outside of the collar as the only part of the nagajuban that is visible.

Finally, it’s time to put on the actual kimono. Remember: left over right to finish. Start by wrapping the right side of the kimono over the left side of your body, then wrap the left side of the kimono over the right. Only the dead have their kimono styled right over left. To prevent any side-eye or judgment from bystanding busybodies, take note of this easy trick: Always have the collar make a “y” shape.

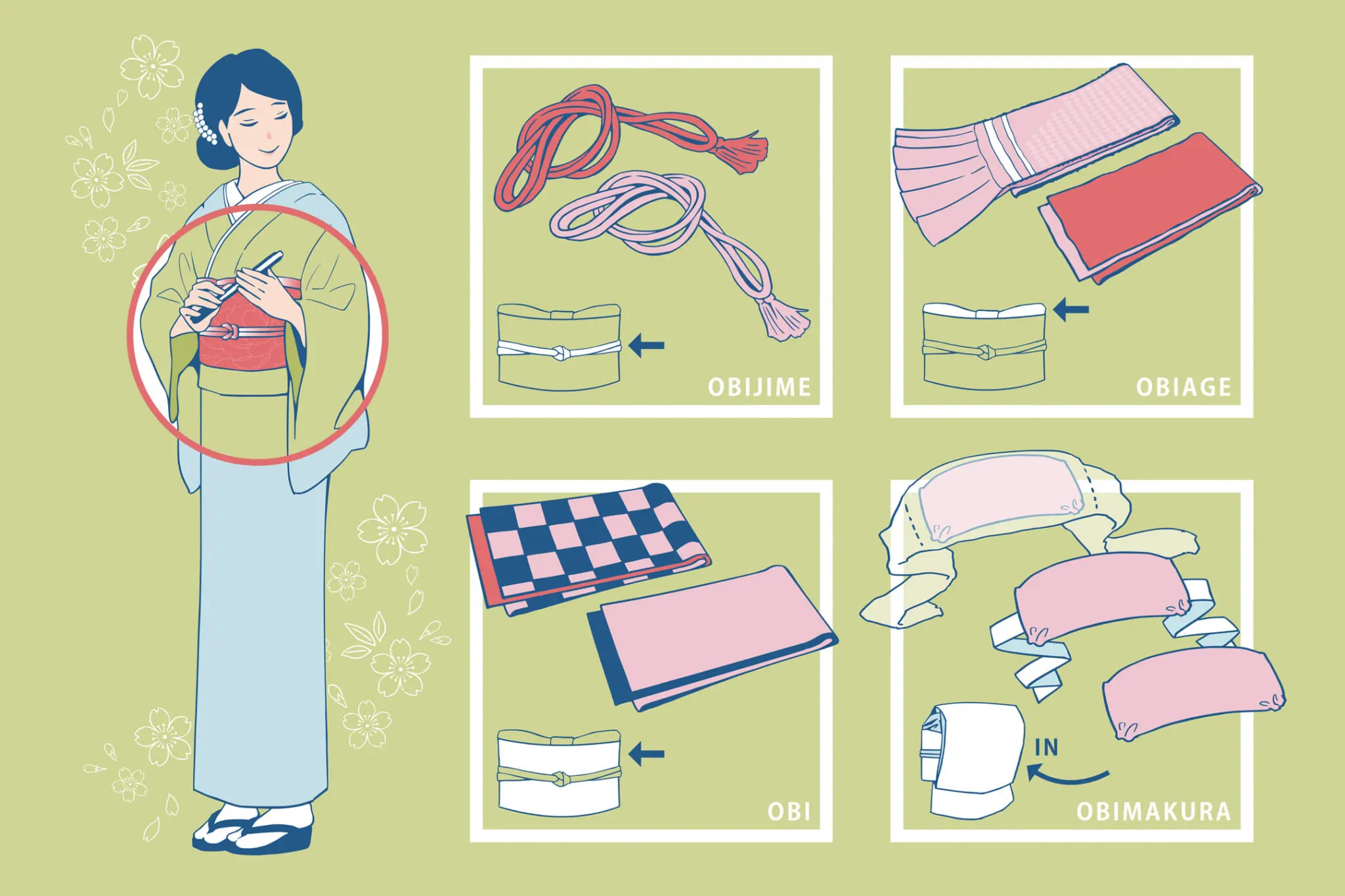

Himo ties and datejime flat belts are used to hold everything together snugly. An obi is tied tightly around the torso with a maeita board belt to keep the obi smooth and taut. Depending on the style of knot, an obimakura (obi pillow) is fastened on the back to cushion a layer of the obi. The obimakura helps shape certain knots, especially those used with formal kimono. It’s positioned and hidden with an obiage scarf, which provides structural support as well as flair and is tied at the front and fully or partially tucked into the upper edge of the obi. An obijime cord — also both functional and ornamental — is fastened around the obi. An obidome charm or brooch can be attached to the obijime cord as a fashionable accessory to complete the ensemble.

During the tying process, extra cloth ties and even clips can be used to aid with placement and to temporarily hold folds in place. Keep in mind, too, that there are several types of obi and even more variations on how to tie them, opening up a huge variety of options when it comes to style, simplicity and kitsuke level.

Kimono Hazuki specializes in bold and colorful antique kimono.

Where To Buy Kimono

Kimono have a wide price point. While you can easily find secondhand pieces from around ¥1,000, at luxurious kimono ateliers, garments go for around ¥200,000. Finding treasures at thrift stores and flea markets is also a thrilling adventure. Here are some recommended shops to check out.

Miyoshiya

Miyoshiya, on the basement floor of Nakano Broadway, has a huge selection of secondhand kimono, yukata, haori, hakama, obi, juban, zori and accessories. Indeed, practically anything you’re looking for, Miyoshiya is sure to have something that fits the bill. The basement extends with rack upon rack of garments, with colorful hangers indicating the price level. Prices start at ¥1,200 (white hangers) to ¥11,000 (pink hangers).

Kirakuya Asakusa

Kirakuya, sitting on Asakusa’s Shin-Nakamise shopping street, carries an extensive assortment of used kimono, obi and accessories. Its collection includes unique designs and modern patterns. Be sure to go upstairs — everything on the top floor is ¥1,100.

Kimono Hazuki

Kimono Hazuki, located about eight minutes from Daitabashi Station, is a boutique that specializes in antique kimono. With vintage trunks, furniture, rugs and artwork giving it a retro-chic atmosphere, stepping inside is sure to have you feeling like you’ve slipped back in time. The staff all wear kimono — find their daily ensembles on Instagram — and can be consulted for their expert opinion. While Kimono Hazuki has a higher price point than most secondhand shops, its curated collection makes it a highly recommended stop.

Antique John

The Kunitachi antique shop Antique John boasts a bonanza of well-preserved pieces. The top floor houses a variety of goods and trinkets like old cameras, fine china, Burberry scarves and Americana. Going down to the basement, you’re greeted by shelves stacked full of kimono, haori and obi. Antique John specializes in antique kimono of the Meiji, Taisho and early Showa eras.

Kimono Yamato

If you’re looking to invest in a new garment to enjoy and pass down as an heirloom, Kimono Yamato, a stylish brand with both timeless and modern designs, has plenty of options to browse at its more than 70 store locations across the country. The kimono purveyor, established in 1917, provides a luxury shopping experience, with expertly tailored and coordinated looks for men, women and children.

Modern Kimono Innovation

Looking to incorporate a more subtle kimono look into your everyday wardrobe? Several brands and high-end designers are bringing new life to Japan’s traditional fashion in ways that allow you to do just that.

Around 500 tons of kimono are thrown away every year — and with them, centuries of culture and history are also discarded. Kien, a fashion brand based in Kyoto, upcycles vintage kimono with contemporary patterning to create stylish and luxurious dresses. Mainly working with formal kurotomesode produced between 1970 and 1990, Kien highlights each kimono’s beautiful pattern and delicate embroidery in modern kimono couture. Not only does Kien create classy designs with secondhand kimono, it also contributes to SDGs and cultural preservation.

Another luxury brand using the opulent silks and embroidery of vintage kimono to create artisanal fashion is Amaud. It offers a fully made-to-measure service and designs that include vibrant jumpsuits, jackets, bags and capes. It also crafts accessories such as bracelets and keyrings by repurposing obijime cords.

Made by Yuki came about after Yuki, the brand’s Japanese American designer, inherited her grandmother’s kimono and obi. For Yuki, upcycling kimono is a way to reconnect with her heritage and celebrate Japanese textiles and craftsmanship.

Tokyo Kimono Shoes combines traditional fashion with modern street style. Kimono are remodeled into unique handmade sneakers. The manufacturer, AxT Inc., has been making shoes in Asakusa for over 70 years. Their sister brand, Kimono Reborn Universe, collaborates with designers in Thailand to revive kimono on a global scale to make tote bags, purses and other creative products. Pre-order reservations can be made online, and ready-made models are available at the Tokyo store.

How To Wear Kimono

While few people nowadays possess the know-how to dress themselves in kimono, there are many resources available to help anyone looking to learn how. Beyond those resources — books, videos, classes, etc. — all it takes is passion and persistence. The book Tanoshiku Naru Kitsuke 100 no Kotsu (100 Tips for Making Kimono Dressing Fun) is one of the highest-rated kimono how-tos on Amazon Japan, filled with helpful kitsuke instructions and visuals to put together the best looking ensemble.

Online, talented kimono instructors and influencers give step-by-step tutorials and kitsuke advice — often in English. The majority of the time, they share their knowledge for free.

Kimono Yamato has a comprehensive Japanese-language kitsuke playlist on its YouTube channel. In addition to videos illustrating how to put on kimono and yukata, the channel features videos showing the proper way to tie a variety of obi knots. Each video carefully goes through each step, with views from multiple angles and guides to easily follow along.

For English-language kimono help, check out Billy Matsunaga, a certified kimono instructor and stylist who creates entertaining and informative kimono content online. Her YouTube channel, featuring everything from vocabulary to pop culture analysis, DIY projects, lifestyle vlogs and detailed kitsuke tutorials, is an excellent resource to expand your kimono knowledge on all fronts. Matsunaga also offers online classes and private lessons.

More structured curricula, as well as certification options, are available at the many kimono schools found nationwide. One of those schools, Ichiru, has classrooms in 16 prefectures spanning Hokkaido, Honshu and Kyushu. Ichiru courses range from beginner to advanced, with lessons for the beginner class breaking down to around ¥500 each. The school — certified by the Nihon Waso Kyokai, an association dedicated to making Japan’s traditional clothing more accessible — even offers a free trial lesson. Please note that Ichiru only offers classes in Japanese, and students need to be fluent enough to read the textbook and complete the certification exam.