British fashion has been hugely popular and held a certain degree of importance in Japan for decades now. Paul Smith, Alexander McQueen, Burberry (remember when nearly every high school girl in Japan wore a Burberry scarf?), Margaret Howell and, of course, the grand dame herself, Vivienne Westwood.

Hailing from the Derbyshire town of Tintwistle, Westwood, who sadly passed away on December 29 last year, became a fashion icon and was renowned for being the instigator of punk fashion alongside Malcolm McLaren and their store Sex, which was situated on London’s King’s Road. It became the physical and spiritual home of punk. The King’s Road location later transformed into Seditionaries and World’s End and a general epicenter of disillusioned youth and anarchy.

Recently immortalized on screen by British actor Talulah Riley in Danny Boyle’s superb miniseries Pistol, Westwood is most known for her link with the Sex Pistols and her indelible influence on fashion including Japanese street fashion in the 1980s and 1990s.

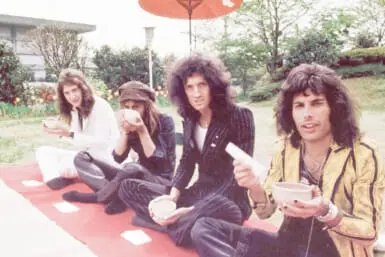

Photo by Andersphoto via Shutterstock

If you picked up a copy of Shoichi Aoki’s seminal Fruits magazine in the late ’90s and early noughties, it was regularly littered with images of Tokyo’s coolest youth proudly wearing Vivienne Westwood. From the punks and Lolita to the more orthodox street fashion boys and girls, Westwood’s influence was everywhere. Fashion writer and author W. David Marx is quoted in Complex magazine regarding Westwood’s social and cultural clout.

“Subcultural fashion in Japan really starts from the looks that sprung out of music scenes, namely punk and hip-hop.” he writes. “The influence is so deeply baked in at this point that it’s easy to overlook, but thanks to Westwood and Rei Kawakubo, punk deconstruction has been a core principle of Japanese fashion for the last 40-plus years. While Westwood’s work was much more cerebral and design focused than athletic casual clothing, her irreverence, defiance, and DIY ethos are all foundational to the spirit of streetwear.”

Westwood and Comme des Garçons designer Rei Kawakubo are generally seen as leading figures in Japanese fashion during the ’90s and 2000s, with both women channeling their penchant for punk, anarchy and social disobedience with Kawakubo, in her Fall/Winter 2003 collection for Comme des Garçons, riffing on some political slogans which were reminiscent of 1960s protest shibboleths such as “Sous les Paves, La Plage!” (Under the paving stone, the beach). Kawakubo appropriated Soren Kierkegaard’s “The majority is always wrong,” mixed in with other slogans including “Conformity is the language of corruption,” which are themselves reminiscent of Westwood’s seminal and controversial T-shirts from the 1970s.

Liam Hess writes in Dazed Digital, “Westwood recognized the potential of the T-shirt as a blank canvas for more overt political messages. A number of her designs caused controversy, but a 1975 graphic of two cowboys touching penises actually led to the arrest of one of their shop attendants, who was stopped and later fined for “indecent exhibition” while walking through Chelsea — a dispiriting sign of how little British attitudes had changed towards homosexuality following the 1967 Sexual Offences Act.”

Photo by Robert Way via Shutterstock

Kawakubo and Westwood also shared a love of padding in order to change and subvert conventional silhouettes. In a show from 1994, Westwood used derriere padding, a 17th century garment that accentuated the “derriere” while minimizing the hips. Kawakubo, in her Spring/Summer 1997 collection, which critics crudely nicknamed “the Quasimodo collection,” implemented a series of padding or bumps which could be taken out or put in, depending on the mood of the wearer, with the shape and silhouette changing each time the garment is worn. In some way it resembles the Japanese metabolist architecture movement from the ’70s. Architecture and design which can be transformed and plugged, played and renewed and refreshed from time to time. When asked about the “lumps and bumps” or “Quasimodo” collection, Kawakubo explained that she wanted to do something different, that she wanted to design bodies rather than clothes. An act I think Westwood would testify to doing also.

Claudio Divizia via Shutterstock

Westwood, whose brand is thankfully continuing under the stewardship of her husband Andreas Kronthaler, had an ongoing love affair with Japan, was a fan of Noh theater and said in an interview with Matthew Hernon for Tokyo Weekender, “The more I travel to Japan the more I like it. In Tokyo, I love to walk through Ueno Park and to visit the museums. People here are very well groomed and smart; they are slim and have good posture. I think they like clothes in the English tradition. Young people especially like to put together an individual look.”

Westwood may sadly be gone, but her revolutionary spirit continues and her stores in locations including Aoyama (which just celebrated its 20th anniversary) are still packed with acolytes and customers who want something more from fashion, a cheekiness, a subversion and a defiant show of two-fingers to the establishment.

More Articles about Fashion and Japan

Read on about Japan’s relationship with fashion and Japanese fashion history: