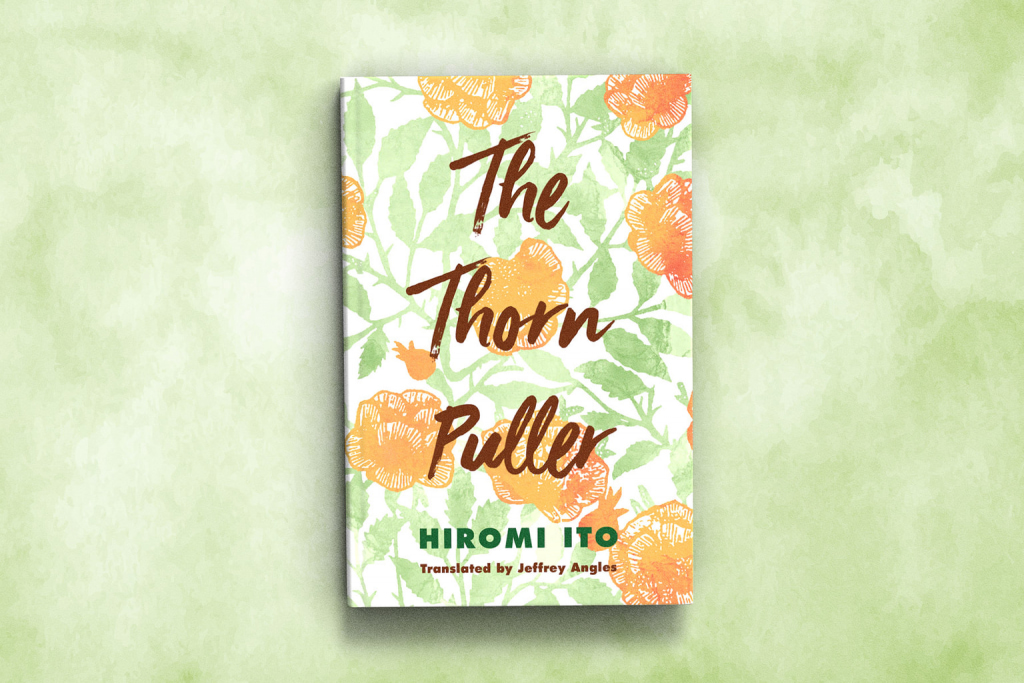

A prominent poet, novelist and essayist, Hiromi Ito first made waves in the literary scene when she won Gendai Shitecho magazine’s award for emerging writers in 1978. Since then, her books and collections have explored a wide range of topics including sexuality, motherhood, the female body and mythology. A few of her many well-known books in Japan include The Thorn Puller, her extraordinary 2007 novel that was translated into English this year, and Heikeiki, a 2013 essay collection on menopause.

The Thorn Puller follows Ito as she spreads herself thin taking care of her sick and aging parents in Kumamoto and a preadolescent child in California, all the while dealing with the conflicts of a cross-cultural marriage. Ito pulls a reader in two directions: into the painful banality of ordinary human struggle, and then into the realm of myths, legends and spirits. She uses shapeshifting literary devices, vividly brought to life by translator Jeffrey Angles in English, to explore universal suffering with one-of-a-kind style. We talked to Ito about this impressive literary accomplishment, her approach to writing and inspiration and what she’s working on next.

What authors are the biggest influence on you stylistically, and who were you reading the most when writing the Thorn Puller?

I was reading a whole bunch of different things. There was Record of Miraculous Stories from Japan (Nihon ryoiki), a series of strange and often sexual stories compiled by the Buddhist monk Kyokai in the eighth century. I read the Hosshinshu, a series of stories about people secluded from the world, written by Kamo no Chomei in the late 12th century.

I’m also a big fan of sekkyo-bushi, a type of narrative that developed among commoners several centuries ago during Japan’s medieval period. Sekkyo-bushi combines elements of prose, poetry and song in fairy tale-like stories about the suffering of ordinary people and the miraculous help that comes from deep prayer and fervent belief. When I started working on The Thorn Puller, I wanted to write something that would be like a contemporary sekkyo-bushi. I chose to focus on the Thorn-Pulling Jizo, a Buddhist figure still worshipped at a famous temple in Sugamo, located near the part of Tokyo where I grew up.

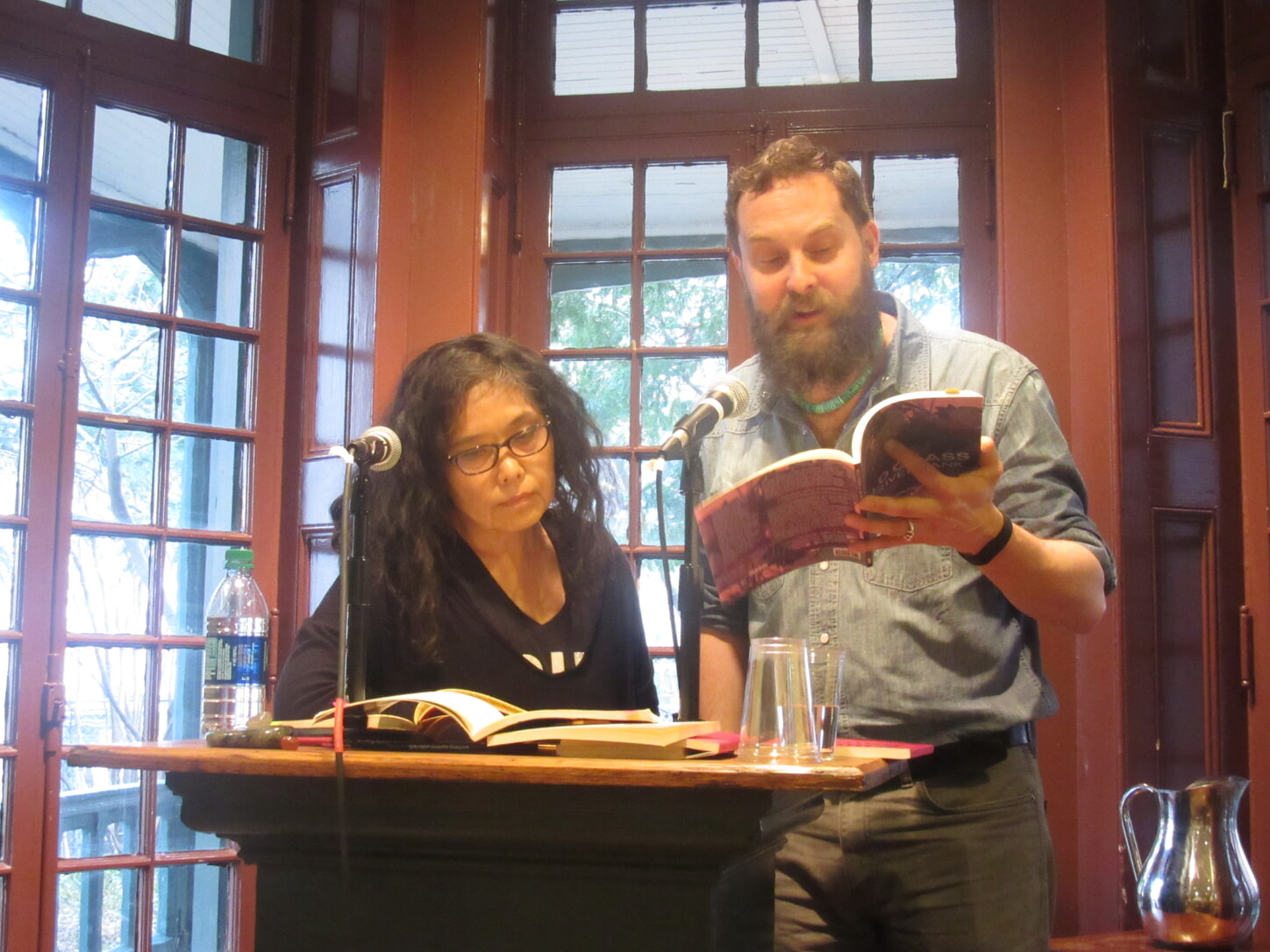

Hiromi Ito, photo by Jeffrey Angles during her visit to Kalamazoo, MI in Oct 2008. Via Wikimedia Commons.

What was the most difficult part to write, and why? Which was the most fun?

The most difficult scenes to write were the ones involving the fights with my partner. It was difficult for me to respect him while still making him the antagonist of the plot.

Because I described our fights in such intimate detail, I made a request to Jeffrey, my translator, that he wait until my partner died before translating the book.

Despite our many years together in California, my partner never learned more than a few words of Japanese, and most of those were related to food. I didn’t want my partner to know how I’d used exaggerated descriptions of our most difficult moments in my work. That would just lead to more fights.

I had the most fun writing the descriptions of plants that appear in each chapter. I’m obsessed with plants, especially those that grow spontaneously, thriving outside of the places where they were necessarily meant to be. Plants teach us how to think differently about our own existences, our own belonging and our own mortality.

How much back-and-forth happened with the translator? Was there anything you were worried would be especially difficult to translate?

There were times when we would discuss things back and forth, but Jeffrey and I have had a long relationship, so he knows my voice, my aesthetic tendencies, and really understands my world. I told him early on that it wasn’t necessary to follow the Japanese text slavishly. In fact, I encouraged him to find creative solutions to any issues that might arise, such as how to bring out the humor in the book (after all, humor is totally different in each language) and how to fill in cultural information that might be unfamiliar to English readers. I have 100 percent faith in his work.

The Thorn Puller uses the innovative literary technique of “borrowing voices” from other poets and authors and weaves them seamlessly into the text. How did you come up with this approach?

When I’m speaking in English, I think (for about a tenth of a second), ‘That word, that expression – I remember when so-and-so said that, in such-and-such tone of voice,’ and then I remember the situation. Ever since I started speaking English regularly, I’ve been increasingly attuned to the different sorts of words and expressions that people use, even in Japanese. In doing so, I’ve realized that I repeat those expressions, using them in my own speech.

A poetry reading by Hiromi Ito with translator Jeffrey Angles at Kelly Writers House (2018).

The Thorn Puller is a book about suffering. What is your message to readers who are suffering in all sorts of ways in their lives?

Since writing The Thorn Puller, I’ve continued to think even more deeply about the role of suffering in our lives. As Buddhism teaches us, suffering is a fundamental part of being alive. Through translating numerous classic Buddhist texts into contemporary Japanese, in other words, through thinking about the nature of life and death, I’ve realized that everyone — every single person — will die. But until the point that we do, we live.

What writing are you working on nowadays?

Since publishing The Thorn Puller some years ago in Japanese, I’ve translated some of the Buddhist classics. For those, see my books The Heart Sutra Explained and We Die One Day but Live Until Then.

I’ve also spent a lot of time observing the cycles of nature. As a way of thinking through life and death, I’ve written a couple of books about plants and about my dogs. I’ve cared for many plants and animals over the years and have watched them go through their own processes of aging and dying. I also used the works of the Meiji-period author Mori Ogai while thinking about the death of my partner and the huge earthquake that struck Kumamoto in 2016, the town in Japan where I currently live.

Right now, I’m thinking about Ruth Stiles Gannett’s children’s book My Father’s Dragon and that has led me to writing about the experiences of my parents living through World War II and its aftermath (at least from my perspective). I was among the first generation of children to read My Father’s Dragon in Japan, which was published in 1948. It’s nice that it was recently turned into a film for Netflix.