Delve into the world of Japanese piracy, where a disgruntled government official commanded thousands of marauders, a maritime clan controlled the Seto Inland Sea and a band of multiethnic sea rovers battled the Spanish far from Japan’s borders

One of the many reasons behind the popularity of One Piece is its pirate theme, a thing rarely seen in Japanese pop culture for many different reasons that mostly boil down to people misrepresenting history for their own gain. And that’s a shame because the actual history of Japanese piracy is long, complex and full of fascinating characters like the country’s real-life pirate kings. Let’s talk about a few of these wannabe Luffys:

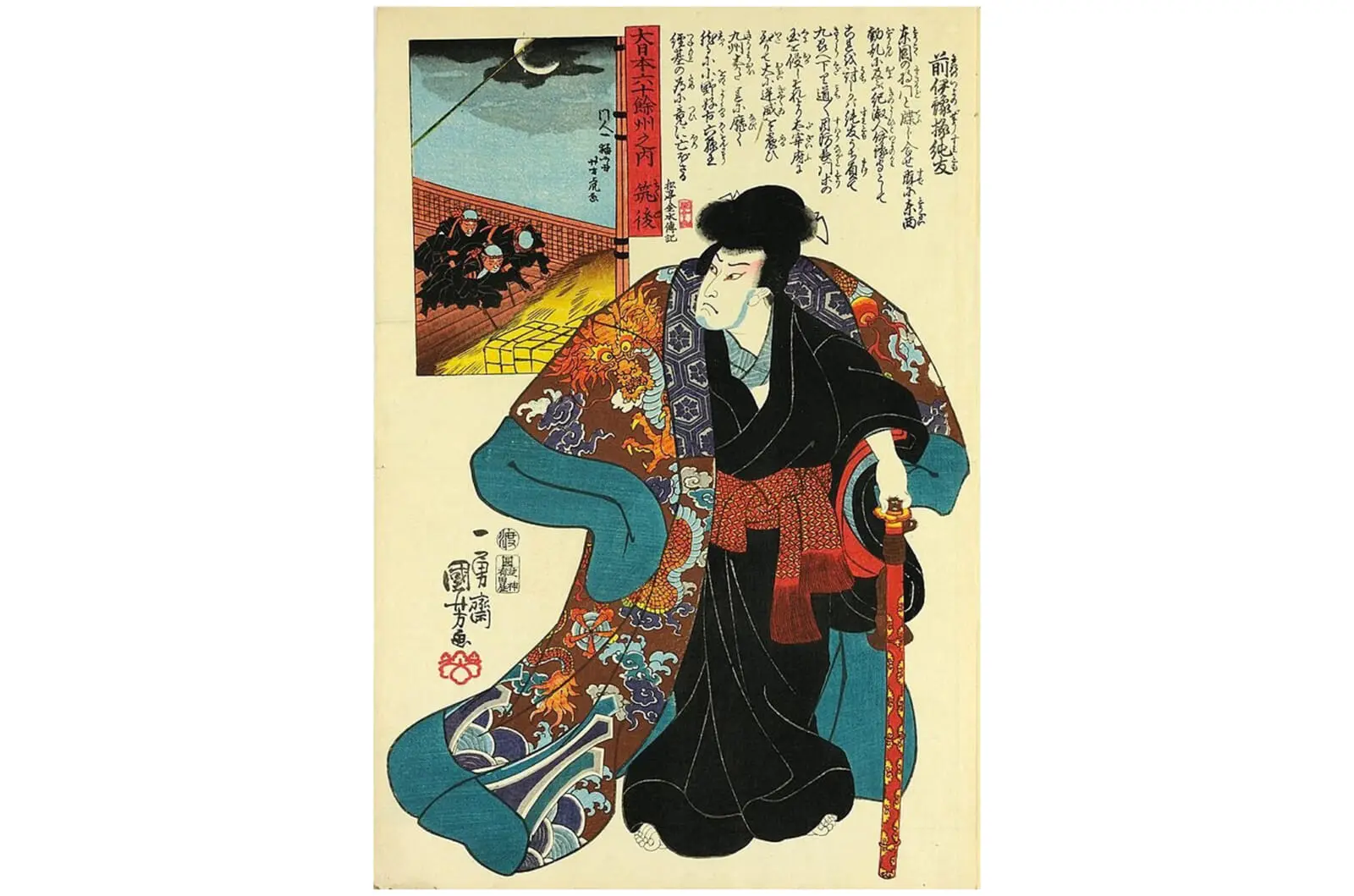

Fujiwara no Sumitomo Found Piracy Easier Than a Career in Government

Around the 930s, Fujiwara no Sumitomo was appointed as military commander of Iyo Province (modern-day Ehime Prefecture on Shikoku), a minor post for a then-unremarkable noble of the seventh rank, one of the lowest in the imperial court system. The ambitious Sumitomo saw a chance to prove himself when Iyo was ordered to subdue local pirate activity. However, after accomplishing the arduous task, he was overlooked for the position of Iyo governor and decided to “do treason” about it.

In 936, Fujiwara no Sumitomo abandoned his post, brought together the surviving pirate factions — even forging new ones from disgruntled farmers and samurai — and created his own pirate kingdom based on Hiburi Island. Some sources say he commanded a total of 1,000 ships crewed by people who followed him because, besides being a skilled fighter, Sumitomo was also an aristocrat, and no matter the rank, that gave him prestige in the eyes of his fellow outlaws.

Soon, Sumitomo controlled the waters around Shikoku, eastern Kyushu and the southern shores of modern-day Okayama, Hiroshima, Yamaguchi and Hyogo prefectures. For a while, the imperial court tried to appease him, as they were more worried about a separate rebellion in the east of the country led by the future “angriest spirit in all of Japan.”

Left to his own devices, Sumitomo disrupted trade and plundered his way through the Seto Inland Sea, once even dispatching his lieutenant to cut off the ears and noses of two provincial governors who were complaining about him to the emperor. However, once the eastern rebellion was quenched, the Kyoto court amassed a large fleet against Sumitomo, thoroughly defeating him during a naval battle in Hakata Bay, where over 800 pirate ships were captured. Sumitomo survived and fled to Iyo, where he was quickly captured and eventually executed. Hopefully, One Piece won’t end the same way.

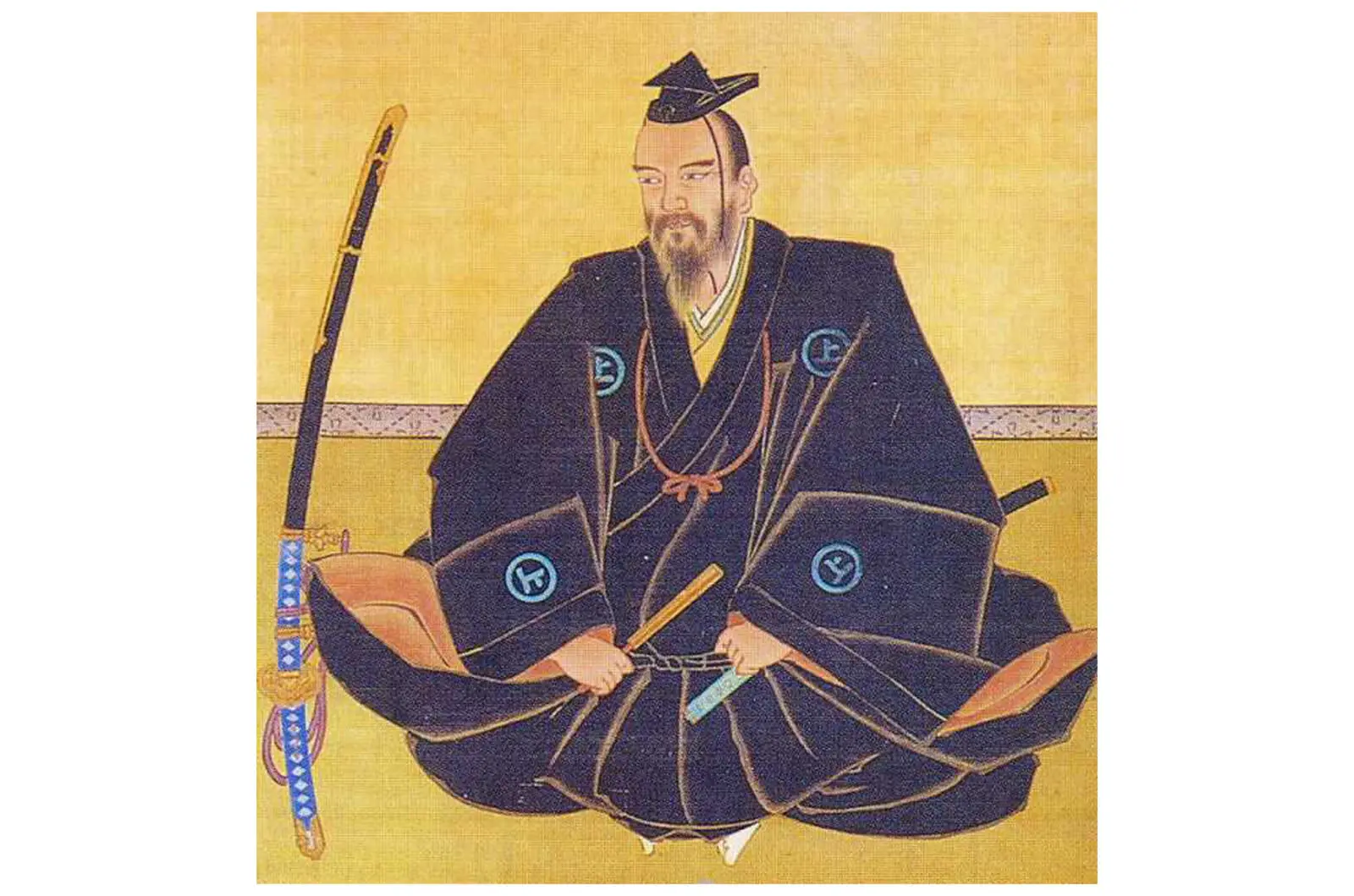

Murakami Takeyoshi Was More of a Water General

In the mid-14th century, the Japanese emperor lost all political power, and a little over 100 years later, the shogun was right there with him. This collapse of a central government eventually led to the Sengoku (Warring States) period, when feudal lords basically acted as kings of their mostly independent realms. Not all of them were located on the Japanese mainland. The Seto Inland Sea is over 400 kilometers long and home to approximately 3,000 islands, a few of which were claimed by the Murakami clan. During the country’s civil war period, the Murakami protected their domains as well as the waters around them, imposing their own laws on strategic trade passages and not answering to any higher authority. Thus, the Murakami Kaizoku (“pirates”) were born.

One of the most powerful Murakami sea lords was the head of the Noshima branch, Murakami Takeyoshi, who all but bled seawater. As king of the narrowest strait in the Seto Inland Sea, he wore a helmet with a golden shell on it, ate octopus before battle (as its eight arms supposedly symbolized protection from all directions) and commanded floating fortress ships that were so massive, they could only move under the power of 80 oarsmen rather than sails.

Hundreds of seafarers and lesser daimyo paid tributes to Murakami Takeyoshi and recognized him as the lord of the Seto Inland Sea. Jesuit missionary Luis Frois described him like this: “He lives in a grand fortress and possesses many retainers … He is so powerful that on these coasts, as well as the coastal regions of other lords’ kingdoms, all make him annual payments out of fear that he will destroy them.”

Takeyoshi was ultimately defeated by the naval forces of Oda Nobunaga during the second battle of Kizugawaguchi, but the legacy of his maritime might is one of the reasons why today, the Murakami Kaizoku are also known as the Murakami Suigun (“water army”).

Tay Fusa Clashed with the Spanish Empire

The wako were East Asian pirates who plundered from Korea all the way down to Okinawa and beyond, and were made up of many different ethnicities, including Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese Hakka, Ainu and, at one point, even Filipino raiders. In the 1580s, a group of wako pirates subjugated the Cagayan Valley in Spain-controlled Philippines, enslaving the local population and taking control of a precious metal exchange center. Setting themselves up in a fort, the pirates briefly turned the area into their own kingdom of terror under the leadership of one “Tay Fusa.”

The name, which supposedly comes from Spanish reports, is most likely a misheard version of taifu-san or taifu-sama, an old Japanese term for a person in charge, like a chieftain or high steward. This is what leads historians to believe that this particular group of wako were led by a Japanese man, though the exact makeup of his crew is unknown. Still, this is far from Japan, and it’s hard to imagine Japanese people making up more than a small portion of the band. The Spanish didn’t really care who was doing the pirating on their turf, though. They just wanted them to stop, so they sent one Captain Juan Pablo de Carrión to deal with the problem.

In 1582, the forces of the Spanish Empire clashed with the multiethnic pirates in what came to be known as the Cagayan Battles. Some websites report this as the only time in history when samurai fought a European army, but there’s no evidence that any samurai were part of this wako group. Some assume that they might have included ronin, but that’s just a guess. Besides, the pirates weren’t using katana but rather spears and firearms, and were clad in breastplate armor.

Another misconception is that there were about 40 to 60 Spanish soldiers (supplemented by Filipino recruits) fighting 1,000 pirates. Researchers who did some basic math based on information about everyone’s ships concluded that, in all likelihood, it was the wako who were severely outnumbered. The entire episode is clad in too much legend based on unreliable sources, but since the pirate activity in the area seems to have decreased after 1582, we can assume that the Spanish put an end to the reign of Tay Fusa. Good. He deserved it for not having any katana-wielding warriors on his crew, robbing us of a real-life clash between samurai and European knights.