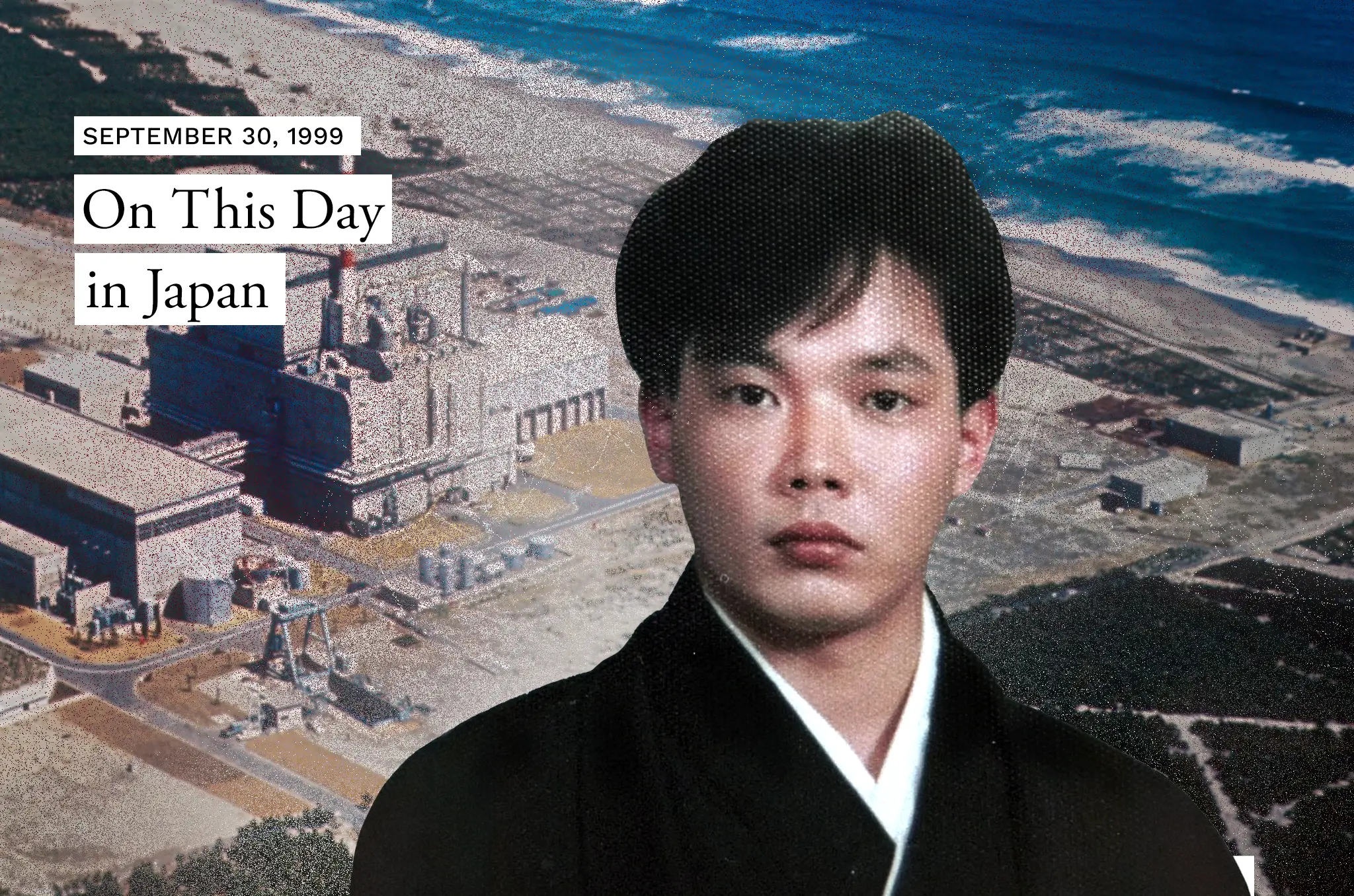

On this day 25 years ago, a criticality accident occurred at a nuclear fuel processing facility in Tokai village, Ibaraki Prefecture. It was, at the time, the worst civilian nuclear radiation accident in Japan’s history. Two workers died as a result of the incident. Hisashi Ouchi passed away on December 21, 1999, following three months of excruciating pain. Masato Shinohara died of multiple organ failure in April 2000. According to doctors, he was exposed to 10 sieverts of radiation. Ouchi was reportedly exposed to a mind-boggling 17. That’s more than three times the dose that’s considered lethal for humans.

Two Major Nuclear Waste Accidents

It was the second nuclear accident to occur in Tokai in two and a half years. On March 11, 1997, an experimental batch of solidified nuclear waste caught fire at the Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation (PNC) radioactive waste bituminization facility in the village. As a result of the explosion, 37 workers were exposed to radiation. PNC waited five hours before reporting the fire to the Science and Technology Agency (STA) and mandated its workers to falsely report the chronological events leading up to the accident.

The incident on September 30, 1999, at the JCO fuel preparation plant — just over 6 kilometers away from the PNC facility — was far more serious. At around 10 a.m., Ouchi and Shinohara entered the processing area of the plant. With their supervisor, Yutaka Yokokawa, looking on from an adjacent room, the pair were tasked with preparing a small batch of fuel for an experimental fast-breeder reactor called Joyo with uranium enriched to 18.8% U-235. Ouchi and Shinohara were accustomed to working with less than 5%. They had no formal training to prepare for the task and were unaware that the operating manual guidelines weren’t approved by the STA.

With JCO under pressure to meet shipping demands, the workers decided to speed things up. Instead of following the standard procedure of feeding the uranium solution through a device that measures the proper amount to be distributed into the precipitation tank, they decided to pour it in directly using stainless steel buckets. The vessel was designed to hold no more than 2.4 kilograms. By 10:35 a.m., they had inserted more than 16 kilograms. They then saw a flash of blue light. This was a result of Cerenkov radiation, which is the electromagnetic equivalent of the sonic boom.

Hisashi Ouchi’s 83 Days of Hell

With gamma alarms sounding, the three workers escaped to the plant’s decontamination room before being taken to the National Institute of Radiological Sciences in Chiba. Medical and fire teams rushed to the site without special protection. They hadn’t been warned about the danger of radiation. Authorities were only informed of the accident an hour after it had occurred. It took another 60 minutes before news of the incident reached then-Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi. Remarkably, almost 12 hours had passed before a decision was made to tell residents within a 10-kilometer radius of the plant to stay inside.

According to a book by a team of NHK journalists titled A Slow Death: 83 Days of Radiation Sickness, Ouchi, the man closest to the tank, was transferred from Chiba to the University of Tokyo Hospital a few days after the accident. When he arrived there, he was still able to talk. His eyes were bloodshot and his face slightly swollen, but he didn’t have any blisters. Soon, though, his condition began to deteriorate and doctors were at a loss as to how to help him. He suffered severe damage to his internal organs and had near-zero white blood cells.

A peripheral stem cell transplantation — a new form of treatment — was carried out in an attempt to restore his destroyed immune system. Cells from his sister’s bone marrow were administered. While there was some promise early on, the radiation in his body ultimately destroyed the introduced stem cells. Attempting to keep him alive, doctors pumped large amounts of blood and fluids into him every day. His condition, though, continued to get worse. His skin melted and blood leaked from his eyes. On November 27, his heart failed for more than an hour. He eventually died at 11:21 p.m. on December 21, 1999.

Masato Shinohara’s Death and the Aftermath of the Tokaimura Accident

Just over a week after Ouchi’s death, Shinohara was able to breathe in some fresh air for the first time in months as he ventured into the garden at Tokyo University Hospital in his wheelchair. For a brief period, his condition was showing signs of recovery. In late February, however, he was placed on a respirator, as he was suffering from severe breathing difficulties. According to doctors, his body was “ravaged” by radiation sickness. Remarkably, he managed to survive for seven months before dying of multiple organ failure on April 27, 2000.

Yokokawa, who was irradiated by 3 sieverts, was released from the Chiba facility after three months. In October 2000, he was arrested for failing to supervise proper procedures. Half a year later, he and five other JCO employees pleaded guilty to charges of negligence resulting in death. The JCO president also pleaded guilty on behalf of the company, which agreed to pay $121 million in compensation to settle 6,875 claims from people exposed to radiation in addition to affected agricultural and service businesses.

More than 10,000 people were tested for radiation exposure in the weeks after the accident. According to the STA, at least 667 workers, first responders and nearby residents were exposed. Classified as an “irradiation” not “contamination” accident under Level 4 on the Nuclear Event Scale, it was considered low risk outside of the facility. In 2000, the STA revoked JCO’s credentials for operation. That same year, Japan’s atomic and nuclear commissions began regular investigations of facilities. They also launched an expansive education program regarding proper procedures and safety culture.