Born in 1895, Noe Ito was raised in a small fishing village, not too far from Fukuoka. As a teenager, she convinced a wealthy uncle to fund her education in Tokyo, where she attended Ueno Girls High School. It was during this period of her life that Ito was first exposed to the literature and progressive ideals espoused in the modern writing of both Western and Japanese authors. This would then precipitate a close relationship with her high-school English teacher, a man named Jun Tsuji. Her parents, however, had different ideas for her future. As a condition of her continuing her education, a marriage was arranged between Ito and an older man named Fukutaro Suematsu during her second year of high school.

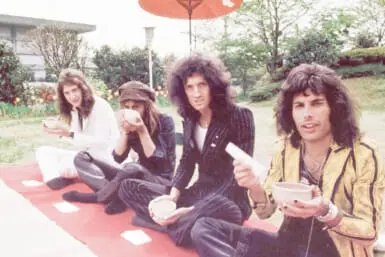

In a desperate bid to avoid this fate, Ito fled the clutches of both Suematsu and her parents and returned to Tokyo, where she hurriedly shacked up with her English teacher. The two began an illicit affair that eventually led to Tsuji forgoing his position as a teacher. Although the relationship eventually disintegrated (Ito discovered Tsuji had been sexually involved with her cousin), the two were officially married in 1915 and had two sons. It was in this same year that Ito, aged just 17, first became involved with Seito, a feminist art-and-culture women’s magazine.

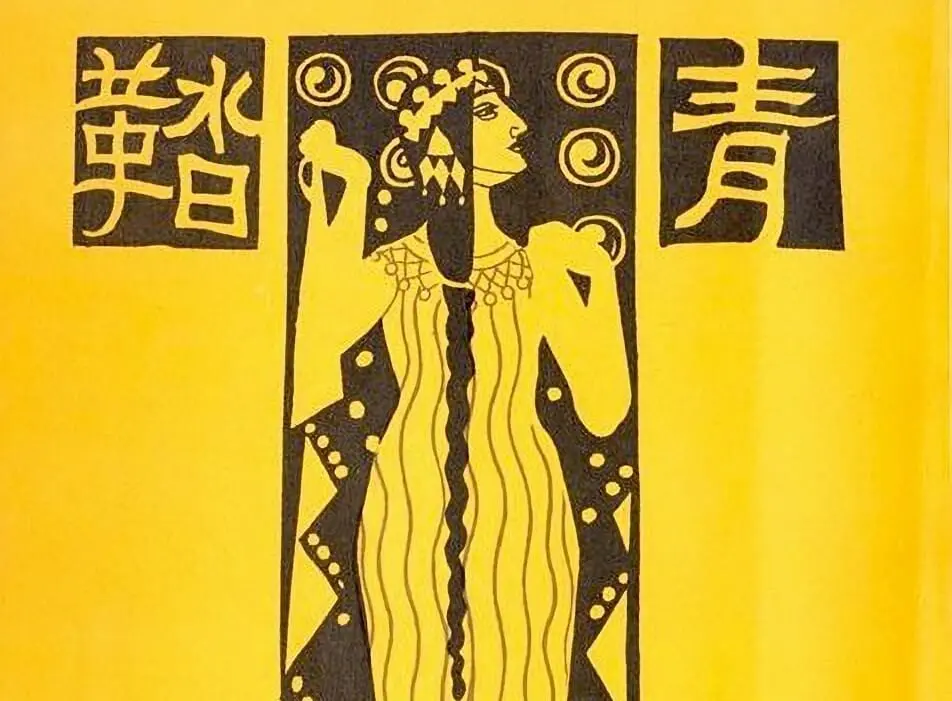

Ito’s Involvement With Seito

Founded in 1911 by five women, including pioneering feminist Raicho Hiratsuka, Seito means “Bluestockings.” The journal’s name was a nod to the “Blue Stocking Society,” an informal women’s social and educational movement in England in the mid-18th century, which had been formed as a space for learned women to gather and discuss literature. Seito became its Japanese sister publication and was similarly devoted to showcasing and nurturing female literary talent.

Ito’s writing for the publication had a strong autobiographical lean. Arranged marriages, the denial of free love and female sexuality were dominant themes in her articles. In the short story “Mayoi,” for instance, published in 1914, the female protagonist discovered that her husband, a former teacher, was still involved with one of her former classmates. While sometimes criticized for dealing too heavily in its emotional underpinning, Ito’s writing was bold, especially in comparison to her compatriots. In fact, scholar Stephen Filler noted her lack of hesitation toward attacking public figures, and her ability to deftly weave together the personal and the political.

At only 18 years old, and the youngest member of the group, Ito became the editor-in-chief of the journal in November 1914. It was to be, by her own reckoning, “a magazine without isms, without policies, without regulations.” Indeed, Seito became increasingly politicized under her helm. Greatly influenced by Lithuanian-born anarchist Emma Goldman, the magazine became a radical force for tackling broader social issues faced by women from all walks of life.

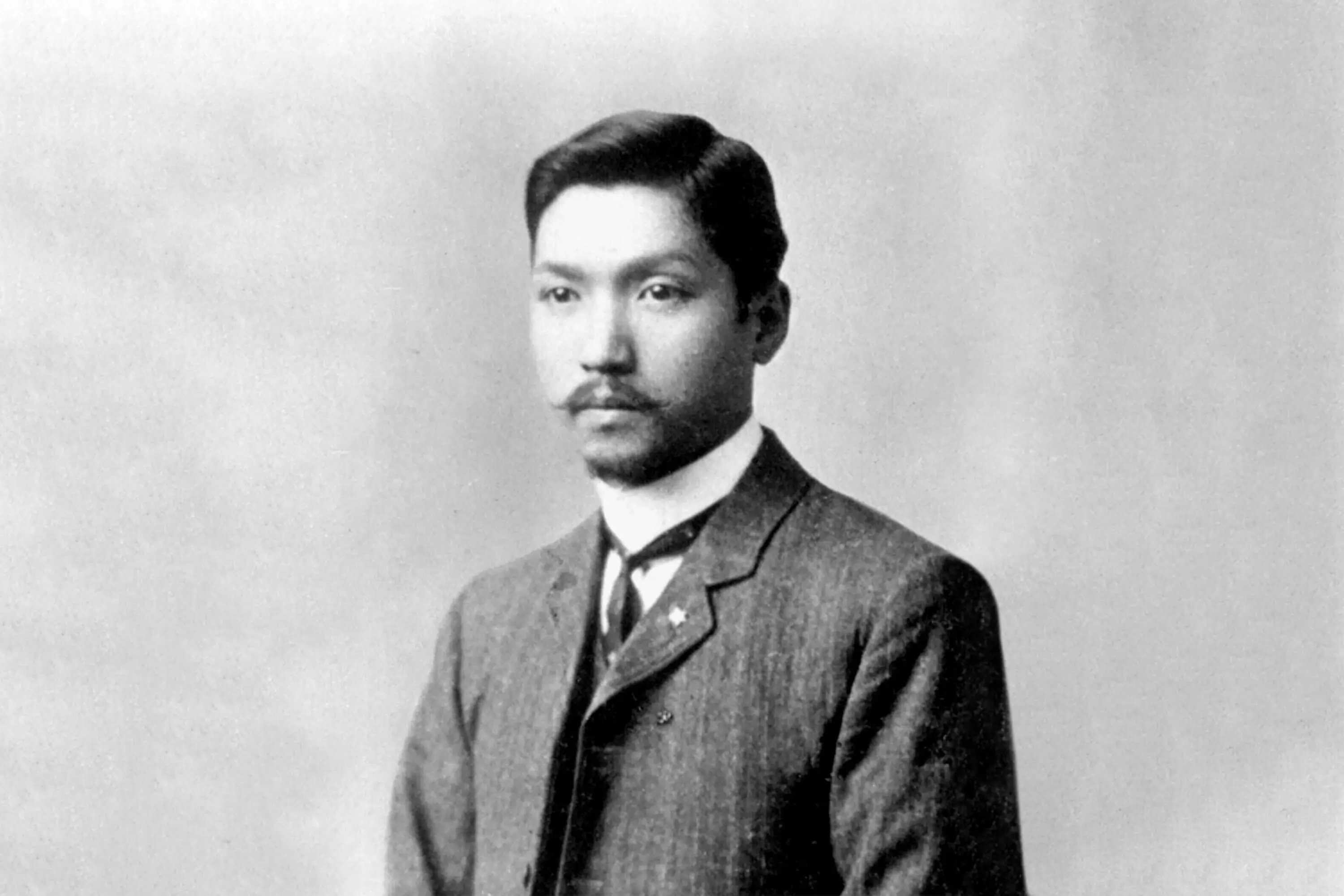

The Sakae Osugi Relationship

Ito’s involvement with Seito, and especially her translation of Goldman’s writing, initiated what came to be a public correspondence with a man named Sakae Osugi, an anarchist political and cultural commentator. As this relationship developed, it quickly became not only professional, but also romantic, thereby cementing the disintegration of Ito’s already-fragmented relationship with her former English teacher.

Following his release from prison — he had been arrested for his involvement in a political rally known as the Red Flag Incident — Osugi adopted a leading role in the post-1911 anarchist movement in Japan. He is credited with catalyzing a shift in the intellectual environment in the country during the late Meiji period (1868-1912).

The End of Seito

Ito and Osugi worked together on both political writings and activism. They also had four children together. The relationship, however, was not particularly well-received by those around them. Osugi followed a doctrine of “free love.” In addition to his relationship with Ito, he was already married, and was also romantically involved with Ichiko Kamichika, another feminist activist and politician. In fact, greatly outraged by Osugi’s polyamorous lifestyle, and fueled by jealousy, Kamichika attempted to stab her lover. Osugi survived and Kamichika was imprisoned for two years.

Ito and Sakae were also alienated by many of their friends and colleagues in the underground socialist movement. As a consequence of Ito’s movement into more radical spheres, tensions began to build with older members of Seito. The magazine also became increasingly censored by Japanese authorities. The 1915 edition was even banned due to its inclusion of an article calling for the legalization of abortion. As funds eventually ran dry, Ito decided to conclude the venture the following year.

While the magazine’s run came to an end prematurely, it is important not to understate the influence that Seito had on the Japanese feminist movement. Many members continued to work as activists for women’s rights. And the existence of the journal inspired writing of a similar nature to be published in more mainstream publications, such as literary magazines Chuo Koron and Taiyo.

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF THE MAIN LIBRARY, KYOTO UNIVERSITY – GREAT KANTŌ EARTHQUAKE: THE WRECKAGE OF ASAKUSA PARK SIXTH WARD

Noe’s Untimely Death

On September 1, 1923, a 7.9 magnitude earthquake violently shook the Kanto region.

There were 187 fires in Tokyo alone. Martial law was announced by the Japanese government the following day in an alleged attempt to contain the chaos that ensued throughout the capital and beyond. However, in the wake of such tumult, rumors began to circulate. Some propagated the belief that it was the Korean immigrant population that had been responsible for the fires that had amassed following the quake. Armed vigilantes, who reportedly included the police, began a series of attacks on Korean citizens in the Kanto region. While any news related to the Korean victims was banned until October 21, it is estimated that at least 6,000 Koreans were killed in Tokyo and Kanagawa alone.

Taking advantage of this considerable turmoil, the Japanese military and police also directed some of this violence towards the leftists and anarchists operating in the area. Ito, Osugi and Osugi’s nephew were all strangled to death on September 16. Their bodies were coarsely disposed of in a nearby well. Ito was only 28 years old.

With Ito and Osugi’s high-profile status, as well as the extreme violence that all three suffered, particularly Osugi’s 6-year-old nephew, the murder sparked outrage and anger throughout the country. Today, it is known as the Amakasu Incident after the military police officer who led the killing.

Ito’s Legacy

Despite dying far too young, Ito established herself as a critical figure in both the feminist and anarchist movements in Japan. Writing and operating decades before women here were even allowed to vote, it’s important to consider just how radical some of her beliefs were. In fact, many of the issues for which she fought remain relevant today. While abortion has been legalized, Japan is one of just 11 countries that mandate that women get their spouse’s consent first. Another point of debate in contemporary society is the call for the legalization of prostitution, which she similarly advocated.

This year marks the 100-year anniversary of Ito’s death, and the pertinence of her beliefs even today is illustrative of quite how much of a visionary she was. There is also, however, a sense of heaviness to this commemoration. Ito’s relevance today underscores just how long female liberation has been an issue in Japan, and the extent to which the battle still remains to be won.