Celebrated in the U.S., Canada, Grenada, Saint Lucia and Liberia, Thanksgiving dates back to a time when the English landed in the Americas. Similar holidays are also observed sporadically across the globe. Incidentally, Japan has its own version of Thanksgiving, Kinro Kansha no Hi, or Labor Thanksgiving Day.

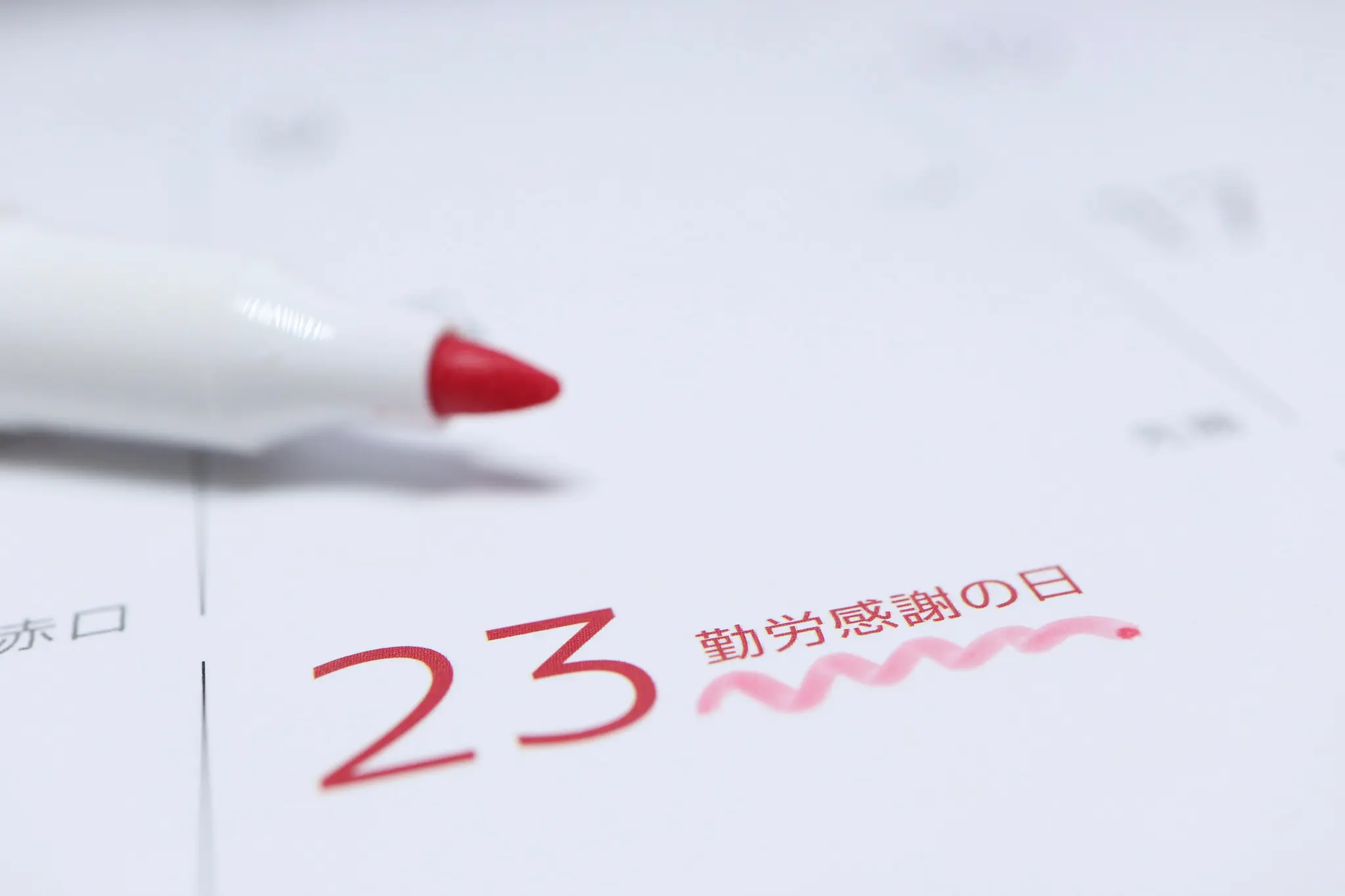

Kinro Kansha no Hi is celebrated on November 23, the same day as this year’s Thanksgiving in America, which is observed on the fourth Thursday of the month. Although celebrated around the same time with similar intentions of gratitude as its U.S. equivalent, Japan’s Labor Thanksgiving Day has its own distinctive history and culture.

Japan’s Labor Thanksgiving Day is celebrated every November 23rd.

The Origins of Labor Thanksgiving Day

The history of Japanese Thanksgiving goes back over 2,000 years, when it was a harvest ritual called Niiname-sai. Mentions of Niiname-sai are chronicled in the Nihon Shoki (the second oldest book of classical Japanese history). The story goes that the holiday originated during the reign of the legendary Emperor Jimmu, back in 660 BCE. Conducted even now in the private quarters of the imperial family and at shrines, the emperor and shrine officials give thanks to the kami (Shinto deities) for a fruitful year. They also offer up harvests for another prosperous 12 months ahead.

The modern Japanese Labor Thanksgiving Day became an official holiday in 1948, the year after the installment of the post-war Constitution of Japan. During the time of the American Occupation, the nation reflected on the brutality of the war and a new role for the imperial family was established. General Douglas MacArthur, meanwhile, abolished all Shinto holidays. The U.S. conducted a sort of issekinicho (killing two birds with one stone) by repurposing Niiname-sai into Kinro Kansha no Hi, away from imperialism and into labor-driven populism. The holiday became a day to express gratitude towards laborers, perhaps taking inspiration from the U.S. equivalent.

How is it Celebrated?

Kinro Kansha no Hi is not celebrated in any elaborate way. No lavish parades grace the streets, and no turkeys are presidentially pardoned. Most people will probably luxuriate on their day off by spending time with friends and family or catching up on rest. There aren’t any particular dishes to be eaten on the holiday either, although seasonal ingredients and rice will probably be present at dinner tables, harkening back to the holiday’s Shinto roots.

Leading up to Labor Thanksgiving Day, however, kids in schools make thank-you notes that are distributed to staff in the labor sector. Companies may celebrate the holiday by thanking their employees, and individuals are encouraged to practice gratitude and care for their well-being. The Nagano Ebisu-Ko Fireworks Festival happens on November 23 each year, though that’s not particularly related to Labor Thanksgiving Day.

Gratitude for Labor

In a country where overworking is a major problem to the extent that the word karoshi was coined — quite literally meaning death by overwork — this relatively unknown holiday carries considerable weight. Labor is the backbone of any nation, and the well-being of the working class dictates healthy governance. Japan sets aside this day to thank our nurses and firefighters, as well as our parents and loved ones who provide for us.

While we have this day off to rest and reflect on all we do, perhaps people in positions of power can find more space to express gratitude and compassion for workers. As this holiday proves, labor is not something that should be taken for granted. In the meantime, celebrate the day by taking a little extra time to check in with yourself, warm up with some cozy, seasonal dishes, and pat yourself on the back. You do much more work than you give yourself credit for.