Many people don’t enjoy receiving sermons about sin, morality and religion, but it’s been going on for centuries, so we’re probably stuck with it. At least Japan had enough sense to make some of their religious lessons visual and badass as hell, with an emphasis on the hell part.

In the Edo and Meiji periods, a figure emerged in Japanese art that represented everything from a condemnation of prostitution to a reminder that all we see is but a dream within a dream. She was called Jigoku Dayu, or the Hell Courtesan. This is her story.

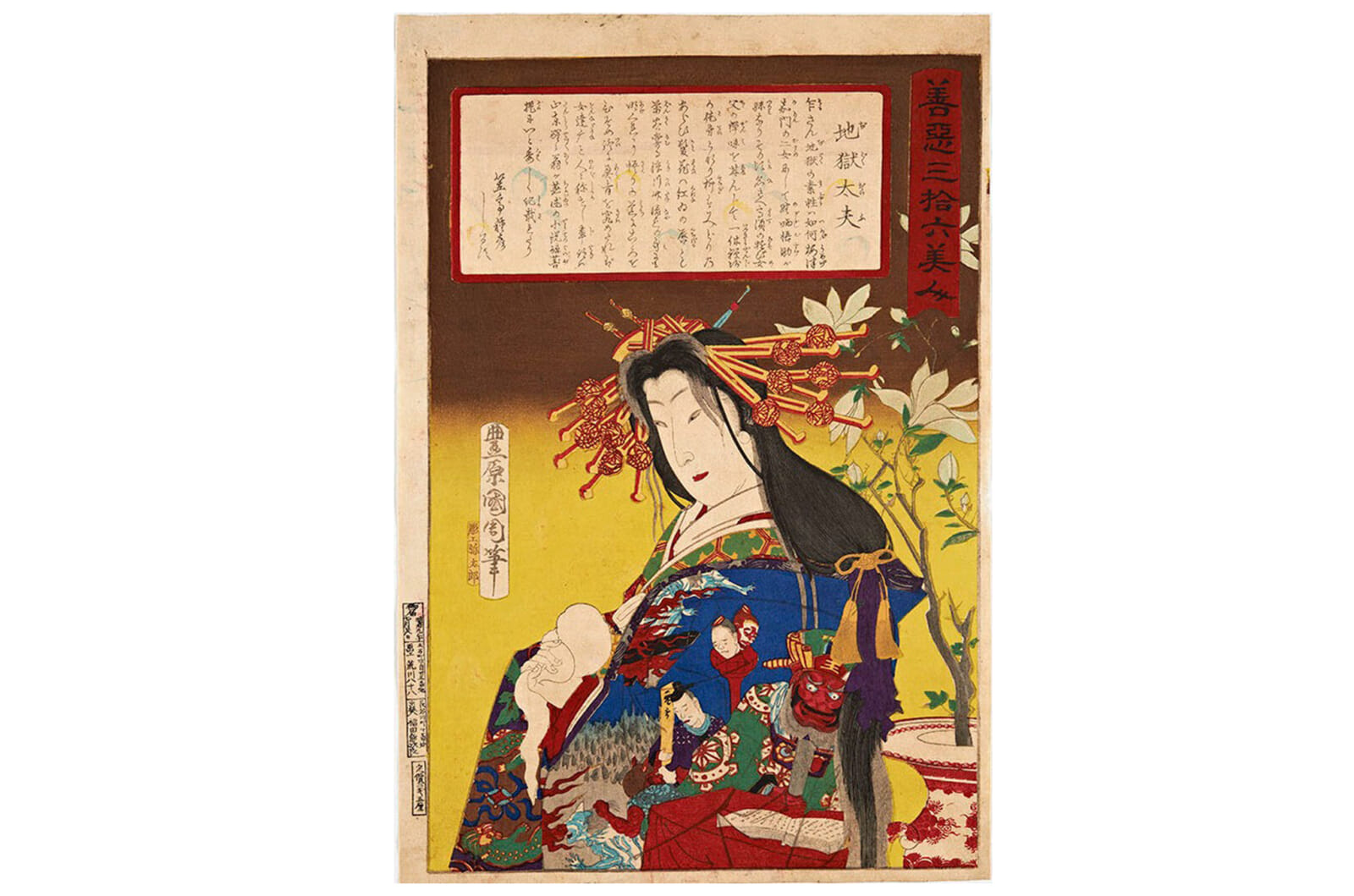

“Jigoku Dayu” by Toyohara Kunichika (1876)

The Devil Wears Prada but Hell Wears a Cool Kimono

For centuries, Japanese artists used paintings, drawings and woodblock prints to explore Hell. Not the place you go to if you wear strong perfume or cologne on a crowded train, but rather a prostitute who changed her name to that of the afterlife’s basement.

A purely artistic invention, the legend of Hell (Jigoku) said that she was kidnapped by bandits and sold to a brothel in Sakai — modern-day Osaka Prefecture — where she concluded that her misfortune was the result of bad karma, in accordance with Buddhist teachings.

To remind herself of her damnation or to try to achieve salvation (depending on the version), she wore a kimono with images of condemned souls, Enma Daio the King of Hell, demons and other hellish scenes.

Every artist tended to put their own spin on Hell’s Boschian wardrobe. Some added Japanese gods to her wearable tapestry. Utagawa Kuniyoshi, for instance, featured the Amida Buddha welcoming the deceased to paradise on Hell’s obi sash. Kuniyoshi loved returning to the theme of the Hell Courtesan so much that he once painted himself wearing a replica of her kimono.

It was fine. This sort of thing wasn’t frowned upon in his days. Prostitution, though? Opinions on that tended to fluctuate in Japanese society, as did the purpose of the Hell Courtesan.

“The Hell Courtesan” by Utagawa Kunisada II (c. 1850s)

Preaching to the Everchanging Choir

In the earliest versions of the Jigoku Dayu motif, Hell wore a kimono featuring the souls of the men she damned by engaging in prostitution. At the time, Japanese society was temporarily of the opinion that prostitution was wrong, influenced by a resurgence of Confucian teachings.

A few years later, they went back to romanticizing it. The prostitutes’ stock then plummeted again and round and round it would go. You can actually track these changes via the depictions of Hell.

She started out as a symbol of societal ills, but then her legend got built up until she became a disciple of the Zen monk Ikkyu. A fascinating real-life figure, Ikkyu’s version of Buddhism included railing against the monastic establishment by eating meat, drinking alcohol and having sex.

In 19th-century art, there were depictions of him meeting Hell while engaging in all three and telling her that prostitution was nothing shameful and that she too could achieve enlightenment. Devoting herself to religious studies, only then did she fashion her famous hard-rock kimono, which would take a backseat in later takes on the Hell Courtesan.

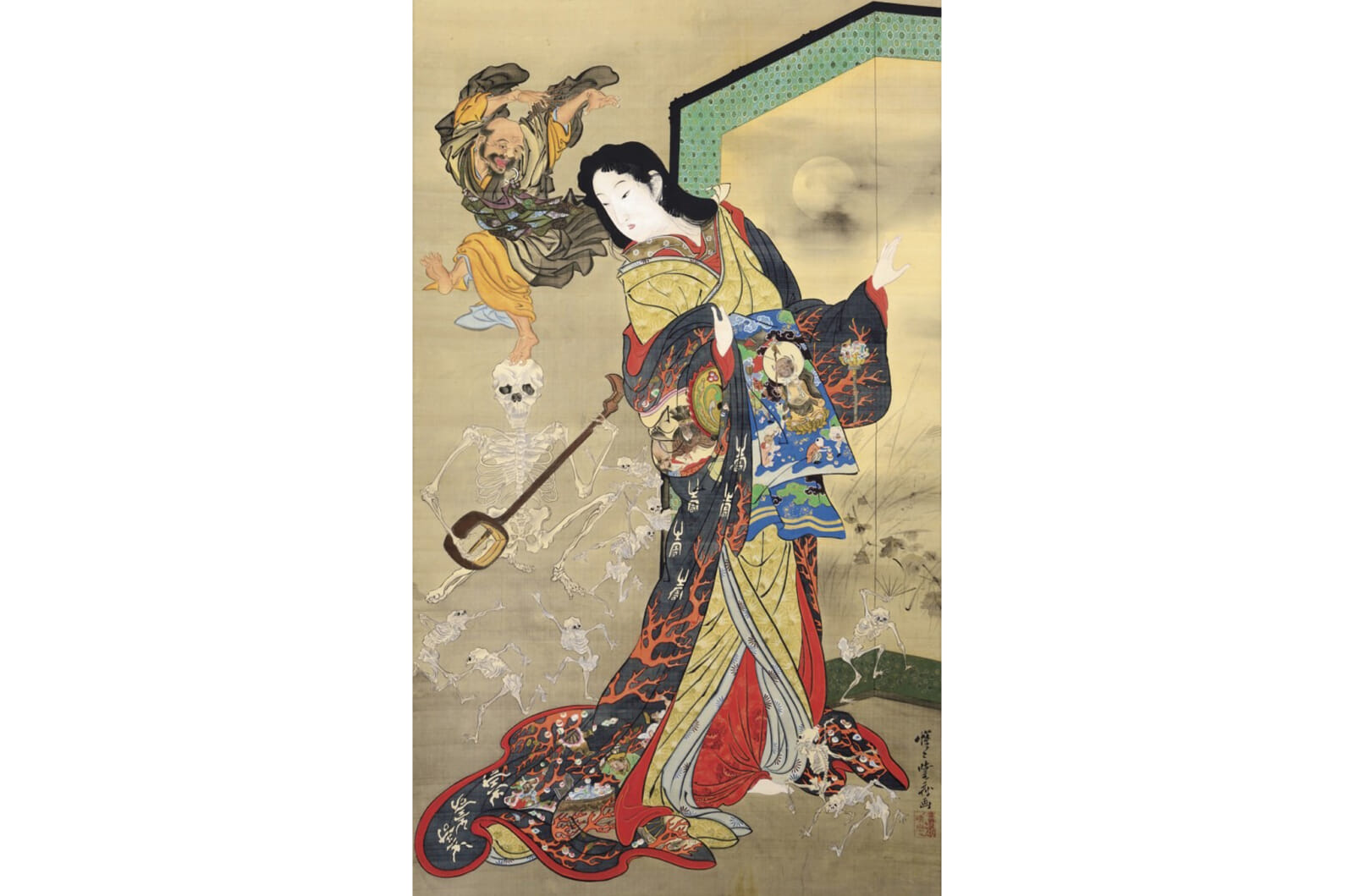

“Hell Courtesan and Ikkyu” by Kawanabe Kyosai (1871-89)

The Japanese Danse Macabre

Hell became convinced that her earthly life was nothing to stress about after she peeked in on Ikkyu supposedly partying with other prostitutes, only to see him dancing and singing with skeletons. After entering the room, though, everything looked fine. Ikkyu then explained that, really, we are all skeletons. It’s just that some of us still have some meat around the bones.

It was his way of saying that every human is destined to die and that our lives are like dreams: fleeting, ephemeral, not actually real or that important. His messaging may have been unorthodox, but that is a pretty good summary of some schools of Buddhism.

As time went on, this Japanese version of memento mori became more prevalent in Jigoku Dayu art. Many portraits of Hell, by the likes of Kawanabe Kyosai and Ogata Gekko, toned down her dress.

Sometimes it would be in the form of frolicking skeletons or Ikkyu walking around with a skull on a walking stick, to remind everyone that was their fate. Nobody ever specified where he got the skull from, but given his wild and unpredictable nature, maybe that question is best left unanswered.

A Kind of Happy Ending

Another common element in the later depictions of Hell was a ceremonial whisk, a shorthand for Zen Buddhism and a sign that, through her studies and devotion, Hell ultimately achieved enlightenment and did not go to her namesake after death.

The Jigoku Dayu trend is thus a fascinating study of duality in Japanese art. Hell was both lowly yet worthy of salvation. Her dress was simultaneously beautiful and terrifying. After her encounter with Ikkyu, she existed between two worlds, embodying sin and enlightenment. It was a complex portrayal that could only have come near or at the end of the Edo period, when the world changed completely for everyday Japanese people.