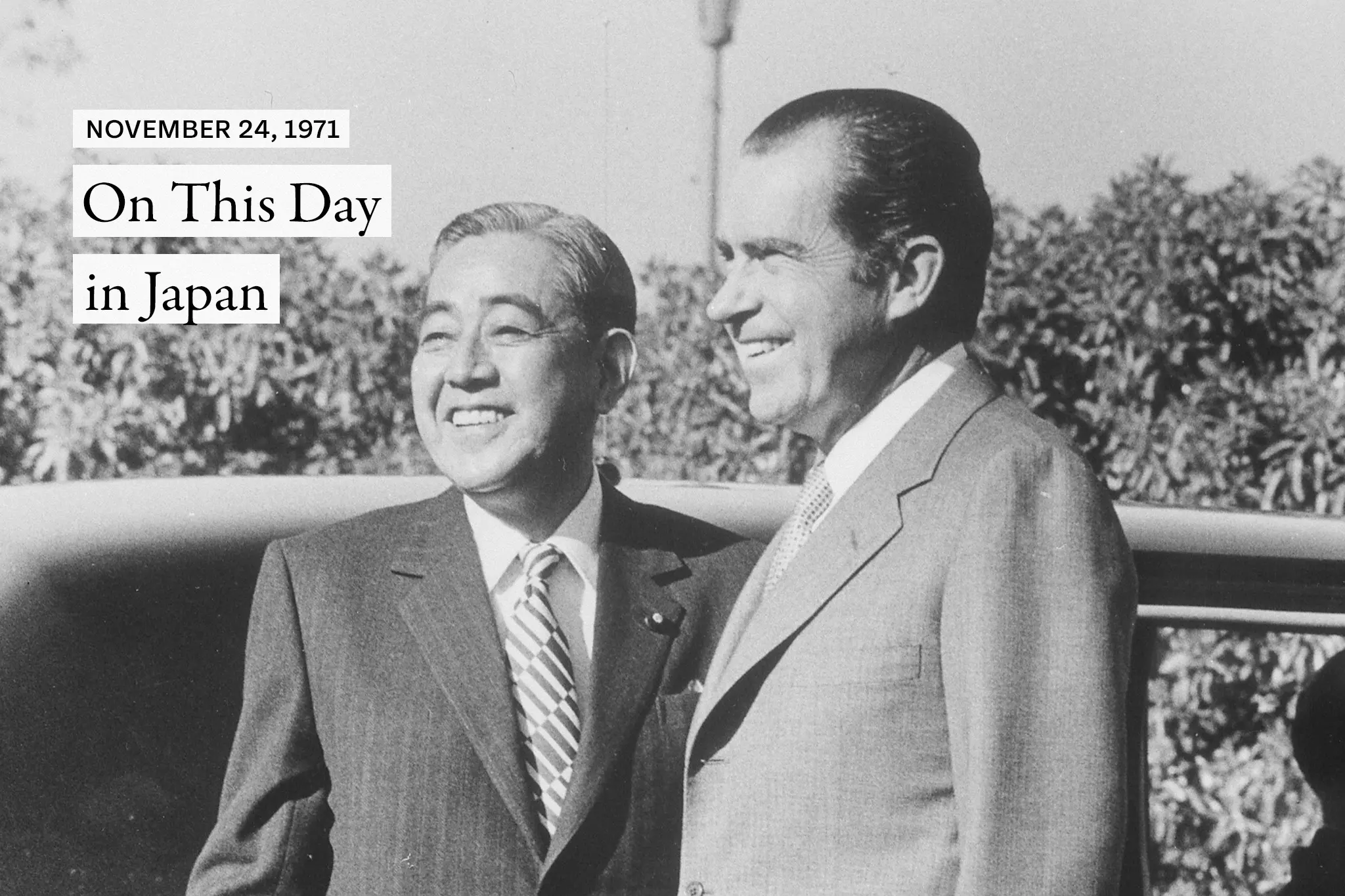

On this day 52 years ago in Japan, the Okinawa Reversion Agreement was ratified by the National Diet. It went into effect six months later, which meant that after 27 years of U.S. rule, Okinawa finally returned to Japan.

Seen as a new chapter in relations between the two nations, the news was celebrated in Tokyo and Japan’s southernmost prefecture, with various ceremonies taking place. However, not everyone was pleased with the agreement, particularly as it meant that American military personnel would remain in the region. More than a half a century on, and their presence continues to stir resentment among many locals.

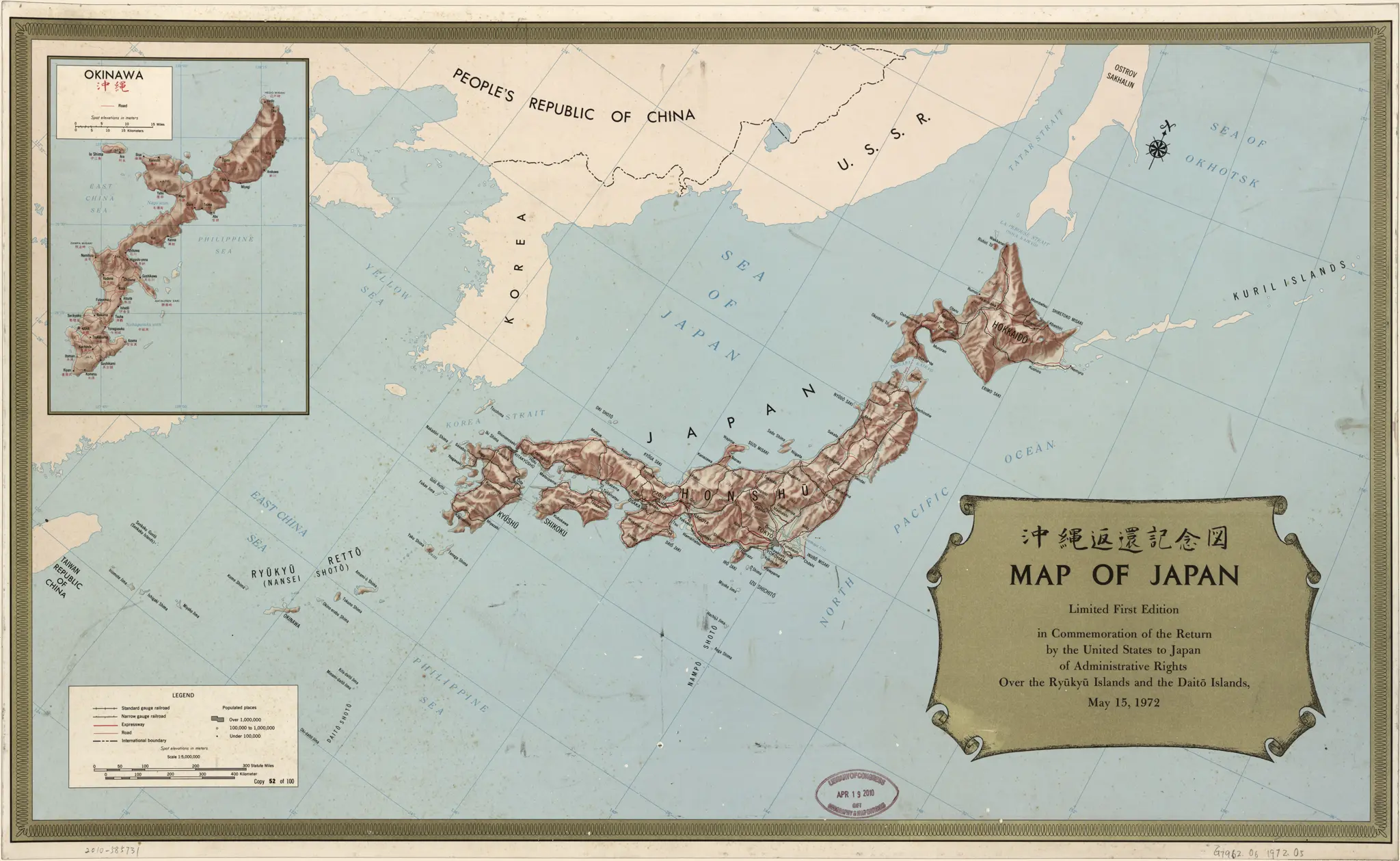

A commemorative map of Japan and the Ryukyu Islands | Wikimedia Commons

Background

At dawn on April 1, 1945 — Easter Sunday — a fleet of around 1,300 U.S. ships and 50 British vessels arrived in Okinawa. It was the beginning of the last major battle of World War II and turned out to be the bloodiest conflict in the Pacific, resulting in a huge number of deaths on both sides, including, according to some estimates, more than 100,000 civilians. After nearly three months of fighting, the American flag was raised over the island on June 22, marking the end of organized Japanese resistance.

The United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands was subsequently established. That lasted until 1950, before being replaced by the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (USCAR). That same year, the governments of the Okinawa, Miyako, Yaeyama and Amami islands were established. These subordinate governments were directed and supervised by the USCAR, who had the authority to unconditionally veto any decisions. This continued even after the end of the Occupation in 1952, though, on December 25, 1953, the Amami Islands were returned to Japan. The U.S. government called it a “Christmas present.”

While Japanese was the main language in schools, the country’s flag was prohibited from being displayed in Okinawa and vehicles had to drive on the right side of the road. Also, the dollar was used as the currency and Okinawans going to mainland Japan needed a travel permit. America’s military presence on the islands, meanwhile, continued to increase. It was viewed as a critical strategic location for the U.S., serving as a staging post for several wars, including those in Korea and Vietnam.

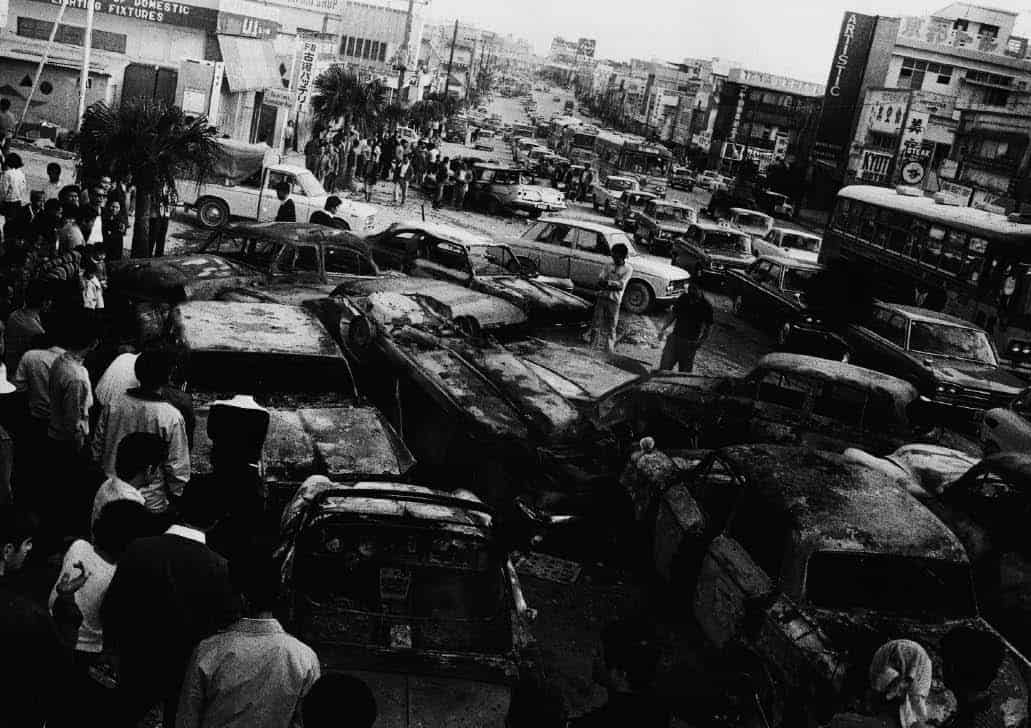

Koza Uprising credit https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com

Anger and Unrest

By the late 1960s, calls for the return of Okinawa to Japan grew louder. Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sato raised the issue with American President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967. However, an agreement wasn’t reached until two years later, by which point Richard Nixon had replaced Johnson as head of state. While the U.S. agreed to remove the nuclear arsenal from military bases on the islands, a secret clause permitted the reintroduction of them in case of an emergency.

Locals were more concerned about the remaining U.S. military presence in Okinawa. Statements from Tokyo and Washington didn’t mention whether the controversial bases, some of which were built after bulldozing people’s homes, would remain. It seemed likely that they would. This annoyed many Okinawans who’d had enough of their land being used as an instrument for war. They were also angry at how the American soldiers behaved, conveying their feelings through protest rallies.

The first demonstrations occurred in 1955 following the rape and murder of 5-year-old Yumiko Nagayama. Sergeant Isaac J. Hurt, the prime suspect, was tried in a U.S. military court rather than an Okinawan civilian one and ended up having his sentence reduced. Local anger intensified in 1967 when a 4-year-old girl was run over and killed by a military crane. It then boiled over three years later after an Okinawan died in a hit-and-run incident. The servicemen involved were acquitted at their court-martial. It led to the Koza riot, with approximately 5,000 Okinawans clashing with roughly 700 American Military Police officers.

Growing Threat from China

This unrest was never going to stop the Okinawa Reversion Agreement, which was signed simultaneously in Tokyo and Washington D.C. on June 17, 1971. The document was ratified five months later with the U.S. reluctantly relinquishing control of what was seen as valuable territory. Its military bases, however, would remain. Japan officially resumed its sovereignty over Okinawa on a rainy May day in 1972. A ceremony to mark the occasion was held at a hall in Naha. At the same time, a protest rally was staged in an adjacent park.

While some land has since been returned, protests have continued. The largest occurred in 1995 after three U.S. servicemen kidnapped and raped a 12-year-old girl. Around 85,000 residents (police estimated 60,000) participated in the rally. A nonbinding referendum was then held in 1996 regarding the presence of the U.S. military on the islands. Of the 59.52% turnout, 89% stated they would like the number of bases reduced. Shortly after the referendum, an agreement was made to relocate the U.S. Marine Corps Futenma air base from the more densely populated Ginowan region to the coastal area of Henoko city in Nago.

That decision led to more protest rallies. Legal challenges have since delayed the project, which won’t be completed until at least the 2030s. At another referendum in 2019, 72% of voters opposed the plan. The central government, however, remains determined to move forward with the plan. As China ramps up its military exercises around Taiwan — a country closer to Okinawa than mainland Japan — America’s presence in the prefecture is considered more important than ever. Locals, though, believe it’s unfair that their region, which accounts for 0.6% of Japan’s national land area, hosts 70.3% of the U.S. military bases and facilities.

More From This Series

Check out other articles from our On This Day in Japan series: