Okinoshima is an island 60 kilometers off the coast of Kyushu in the Genkai Sea. With its remote location, steep cliffs, primeval forests and almost no infrastructure save for a simple port, it doesn’t look like the most welcoming place at first glance. But the island actually has a lot going for it, the least of which being the fact that it will never have to amend the “population” portion of its Wikipedia page, which is permanently set at one.

The only official inhabitant of Okinoshima is a single Shinto priest tending to the island’s Okitsu-miya shrine (alternatively known as Okitsu-gu, part of the Munakata Taisha Grand Shrine complex spread across a total of two islands and the Kyushu mainland). Well, actually, it’s a series of priests who spend 10-day intervals on the almost-deserted island, but always one at a time.

They have two jobs. One is to chant prayers to Tagorihime, daughter of the sun goddess Amaterasu, one of the most important deities in the entire Shinto pantheon. The second — kind of ironically in light of the previous sentence — is to make sure that no woman ever sets foot on the island.

Munakata Taisha Shrine in Munakata, Fukuoka, Japan. It is part of UNESCO World Heritage Site – Sacred Island of Okinoshima and Associated Sites in the Munakata Region. (Photo by beibaoke via Shutterstock)

Women are strictly prohibited from landing on Okinoshima, the actual cause of which isn’t fully understood. Some say it’s because of women’s links to menstrual blood, which is considered impure by some Shinto schools of thought. Other theories say that women aren’t allowed on Okinoshima to protect them as some Japanese goddesses have been known to be distrustful of potential “rivals.”

In the past, artists specializing in images of Benzaiten, the syncretic Japanese goddess of beauty, music and love, were actually advised to not marry so as to not make the deity jealous about them having another woman in their lives. But there are no such stories about Tagorihime and, besides, she isn’t even the most important deity in the neighborhood. The whole of Okinoshima is.

That in itself isn’t actually that strange. In the Shinto religion, it’s not uncommon for landmasses to be worshipped as gods, which is actually the case with the island of Miyajima, home to the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Itsukushima Shrine. That’s why the complex’s main shrine and torii gate were constructed on the shore and on the water instead of deeper on the island.

When it comes to women, however, they are absolutely allowed on Miyajima. Some Shinto sites still, in fact, exclude female visitors, such as Mount Omine (officially known as Mount Sanjo) in Nara Prefecture. Yet, at least they have historic records proving that the practice goes back centuries. With Okinoshima, no one really knows how the “No Women Allowed” rule started.

Okitsu-gu Yohaisho at Munakata Taisha Shrine in Oshima Island, Munakata, Fukuoka, Japan. It is part of UNESCO World Heritage Site – Sacred Island of Okinoshima and Associated Sites in the Munakata Region. (Photo by beibaoke via Shutterstock)

The Okitsu-miya shrine dates back to around the 17th century, but religious rites were performed on Okinoshima as far back as the 4th century. In all that time, no written account about women being banned from the island has surfaced. In fact, the whole idea sounds contrary to the origins of Okinoshima as a deity.

The best available evidence says that the island was a seafaring guidepost on a trading route to Korea, as well as a harbor for fisherfolk venturing far out into the sea. To ensure safe sea passages through dangerous waters, these mariners would stop at Okinoshima and make offerings of mirrors, bronze dragon ornaments, food and much more. Here’s the thing, though. According to interviews conducted by Dr. Lindsey E. DeWitt from the University of California, it was common for centuries for male-female fishing couples to travel to the island together to make said offerings.

It’s not clear when that changed, but it did, and starting from around the Edo Period (1603–1868), Okinoshima became off-limits to women. That being said, even men had trouble setting foot on the island. There used to be a tradition of allowing 200 men onto the island on May 27 every year, but only after they stripped naked and underwent a sacred rite of ablution.

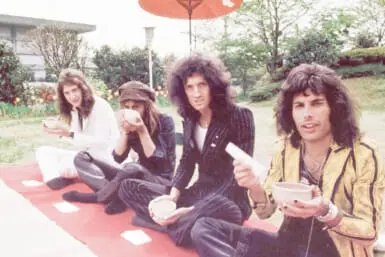

A photo of the purification ritual at Okinoshima.

However, after Okinoshima became Japan’s 21st UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2017, the ceremony was canceled indefinitely. What’s interesting, though, is that while it lasted, every man admitted to Okinoshima was forbidden from removing anything from the island (even a pebble) or talking about what they saw or experienced there. Over the years, this has fueled people’s imagination, earning Okinoshima such nicknames as “The Island of Mystery” and “The Unspoken One.”

That’s all very well and cool, but these supposedly sacred rules weren’t always strictly adhered to. As a matter of fact, huge archeological expeditions had removed much more than pebbles from the island. Currently, the Munakata Taisha shrine’s Shimpokan Museum in Kyushu houses 80,000 precious artifacts, including “bronze mirrors, comma-shaped beads and shards of glass presumably brought to Japan by way of the distant Silk Road,” all taken from Okinoshima. And yet, the island is still standing. So maybe the gods would also be fine with female visitors? Definitely something to think about.