Firearms have been part of samurai culture from the moment they first arrived in Japan to when there were no more samurai around. Even so, the most common place where you would see a gun during Japan’s feudal period was during large-scale battles, typically in the hands of foot soldiers. Many samurai, like the Demon King himself, Oda Nobunaga, respected the power of arquebuses, muskets and pistols, but personally preferred to fight and die by the blade. There are a few recorded exceptions to that, though, and each one went down in history with a bang.

The Teradaya Incident (1866)

The Gun: Smith & Wesson No. 2 Army Revolver

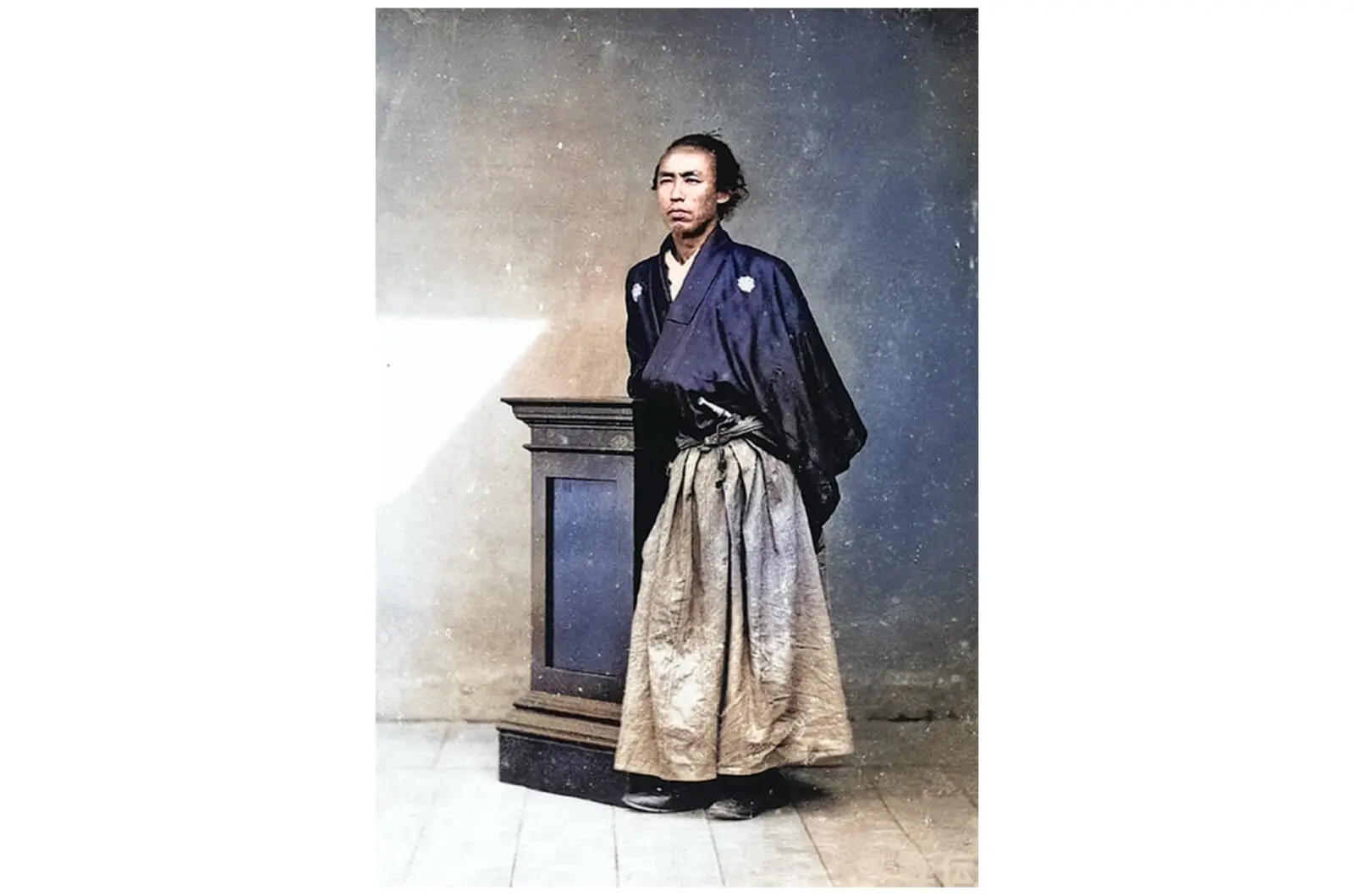

Samurai Sakamoto Ryoma is one of the main reasons why there aren’t samurai anymore. In 1866, he successfully negotiated an alliance between the Satsuma and Choshu domains (present-day Kagoshima and Yamaguchi prefectures), which eventually helped overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate that had been ruling over Japan since 1603. This allowed the emperor to regain political power (which the institution lost in the mid-14th century) and usher in Japan’s modernization period that abolished the feudal system and the samurai class.

The shogunate, however, didn’t just gently disappear. In the last years of its existence, the feudal military dictatorship tried to arrest and assassinate Sakamoto. One such instance was an incident at the Teradaya Inn located just outside of Kyoto.

On March 9, 1866, local shogunate officials stormed the inn after catching word that Sakamoto was staying there, but the adoptive daughter of the inn-keeper, according to legend, leapt out of a bath to warn the samurai about the raid.

Prioritizing the precious seconds he’d been given, Sakamoto didn’t even put on his pants as he readied his swords and a Smith & Wesson revolver. Standing back-to-back with his companion and bodyguard Miyoshi Shinzo, the two samurai then faced 10 opponents.

These were experienced fighters, and Sakamoto quickly received cuts down to the bone on both of his hands. To drive his attackers back, he started shooting blindly until he was down to just one bullet. Using Miyoshi’s shoulder to steady his hand, he successfully killed one opponent using his last round.

In the end, the two managed to escape. Sakamoto and Ryo (commonly called Oryo), the inn-keeper’s daughter, eventually married and went on the first known honeymoon in Japanese history by taking a hot-spring trip to Kirishima.

The Sakuradamon Incident (1860)

The Gun: Japanese-Made Colt 1851 Navy Revolver

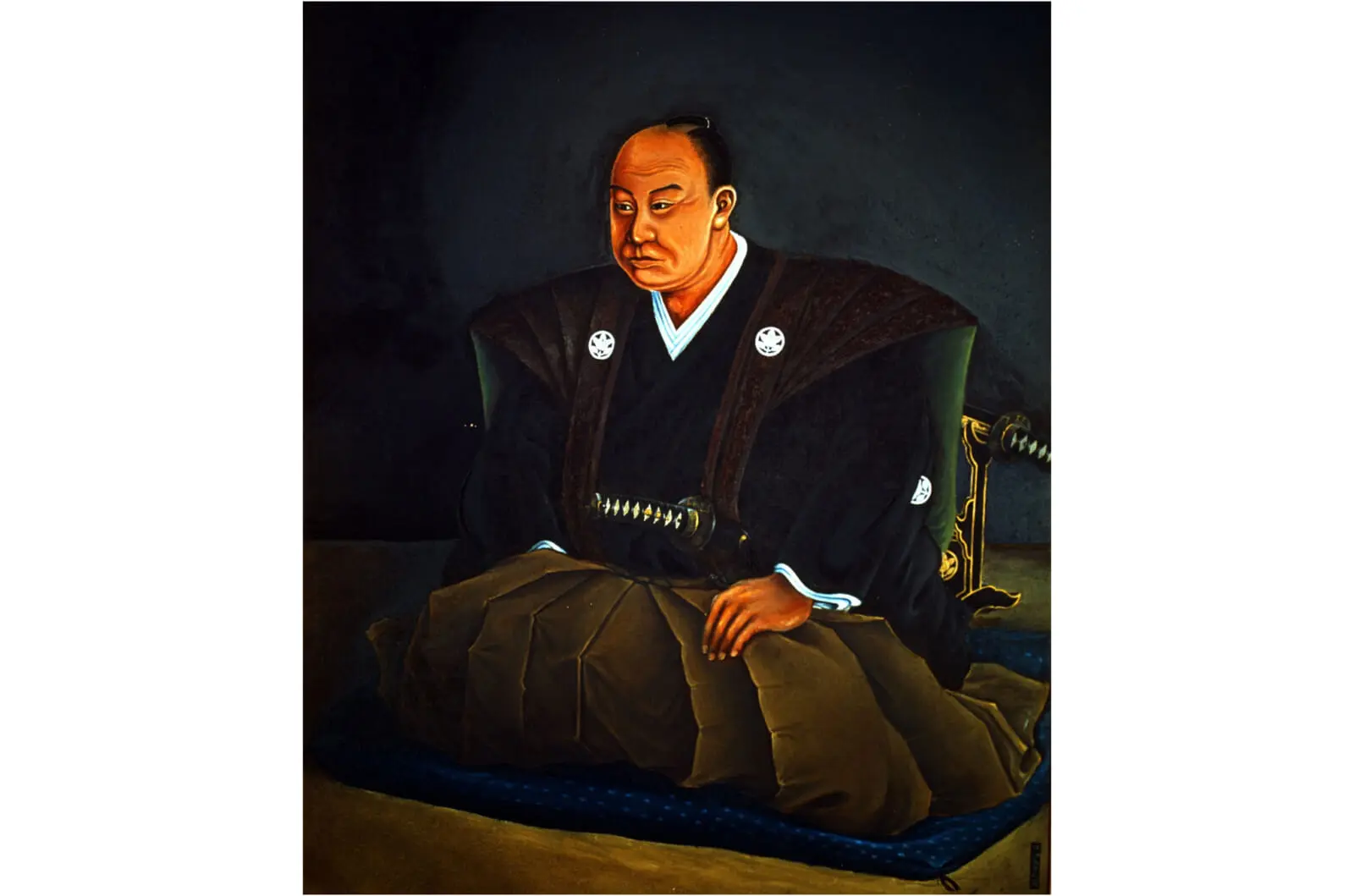

During the Ansei Purge, which took place between 1858 and 1860, the Tokugawa shogunate imprisoned, executed or exiled anyone who didn’t support its authority. It was led by Ii Naosuke who sought out “traitors” all over Japan, often with extreme prejudice.

Naosuke made a lot of enemies through his deeply unpopular political decisions, such as signing the Harris Treaty that opened up the country’s ports to the world on very unequal terms to Japan. He also signed the treaty without the emperor’s permission, which angered royalists, nationalists and even some people in his own camp.

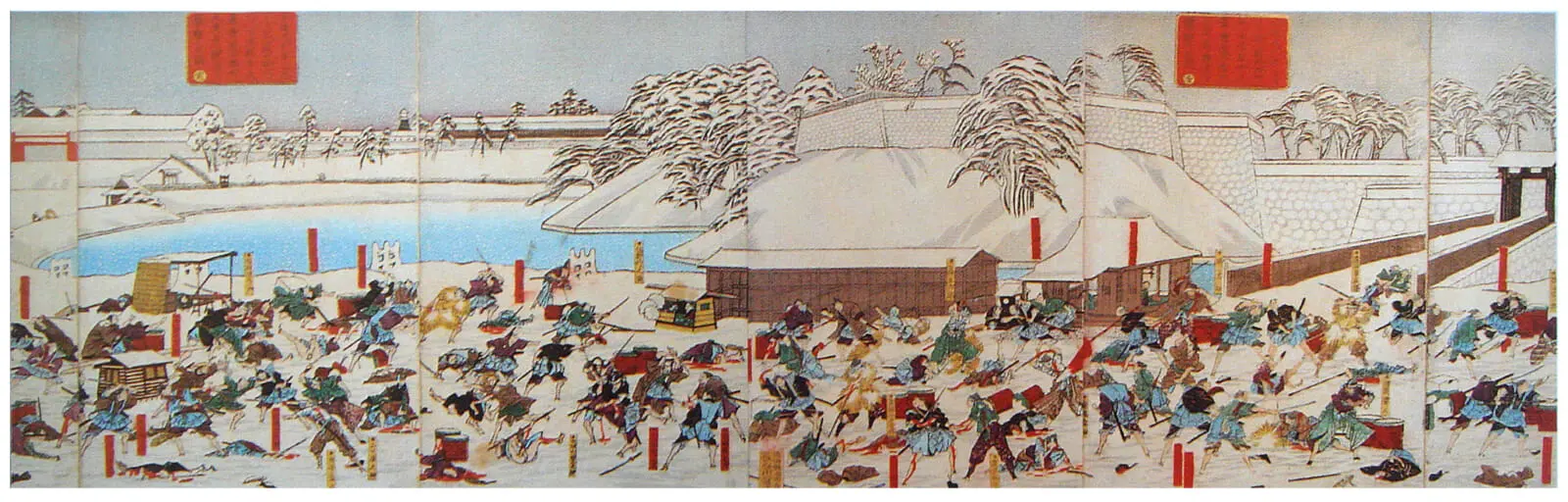

It was just a matter of time before someone took a shot at him. Few people expected that it would be literal, though. On March 24, 1860, near Edo Castle’s Sakurada Gate (Sakuradamon), Naosuke’s palanquin was surrounded by 17 warriors from the Mito domain (modern-day Ibaraki, which was hit especially hard by the Ansei Purge) and one Arimura Jizaemon of Satsuma.

After disposing of Naosuke’s guards, Jizaemon shot into the palanquin with a Colt revolver, reportedly a copy of a gift to the shogunate from the United States and, consequently, a very symbolic weapon against a man being accused of bowing too low to foreign forces. Covered in blood and fatally wounded, Naosuke crawled out of his box and was beheaded by Jizaemon, who then committed seppuku.

Naosuke’s contemporaries did not shed a lot of tears for him, and the assassination quickly became a topic for a series of ukiyoe paintings titled “Righteous Men of Early Modern Times” (“Kinsei Meigiden”).

The Assassination of Mimura Iechika (1566)

The Gun: Sawed-Off Arquebus

Feudal lord Ukita Naoie went down in history as one of the Three Great Villains of the Sengoku period, mainly because later chroniclers were trying to make history fit into some kind of easy-to-follow narrative structure.

This is strange because if you’re going to accuse someone of being a great villain, it should be for something big like inventing a new type of murder, which Naoie possibly did. It’s said that he may have orchestrated the first assassination via a firearm in Japanese history when he ordered the death of rival feudal lord Mimura Iechika.

History isn’t clear on why Naoie chose the Endo brothers, Toshimichi and Hidekiyo, to carry out the task. The two were formidable fighters but, over the years, they started favoring the arquebus over swords, becoming experts in the primitive firearm, which was still an often unreliable tool as they’d soon discover firsthand.

On February 5, 1566, they snuck into Kozenji Temple where Mimura was garrisoning with his commanders. Poking a hole in the paper of a screen door, Toshimichi aimed his “shortened” arquebus (sometimes mistakenly referred to as a handgun) at the target, when suddenly his matchlock went out.

Thinking on his feet, Hidekiyo pretended to be a guard and went to get a flame from a bonfire in the courtyard. Returning to the sniper’s nest, he lit the matchlock and Toshimichi successfully shot Mimura dead.

In the ensuing chaos, the brothers miraculously escaped the temple and were made fief-holding generals in Naoie’s army for their efforts. In the end, their story teaches us that killing does pay as long as you kill the right person. That’s not a great lesson but that’s history for you.