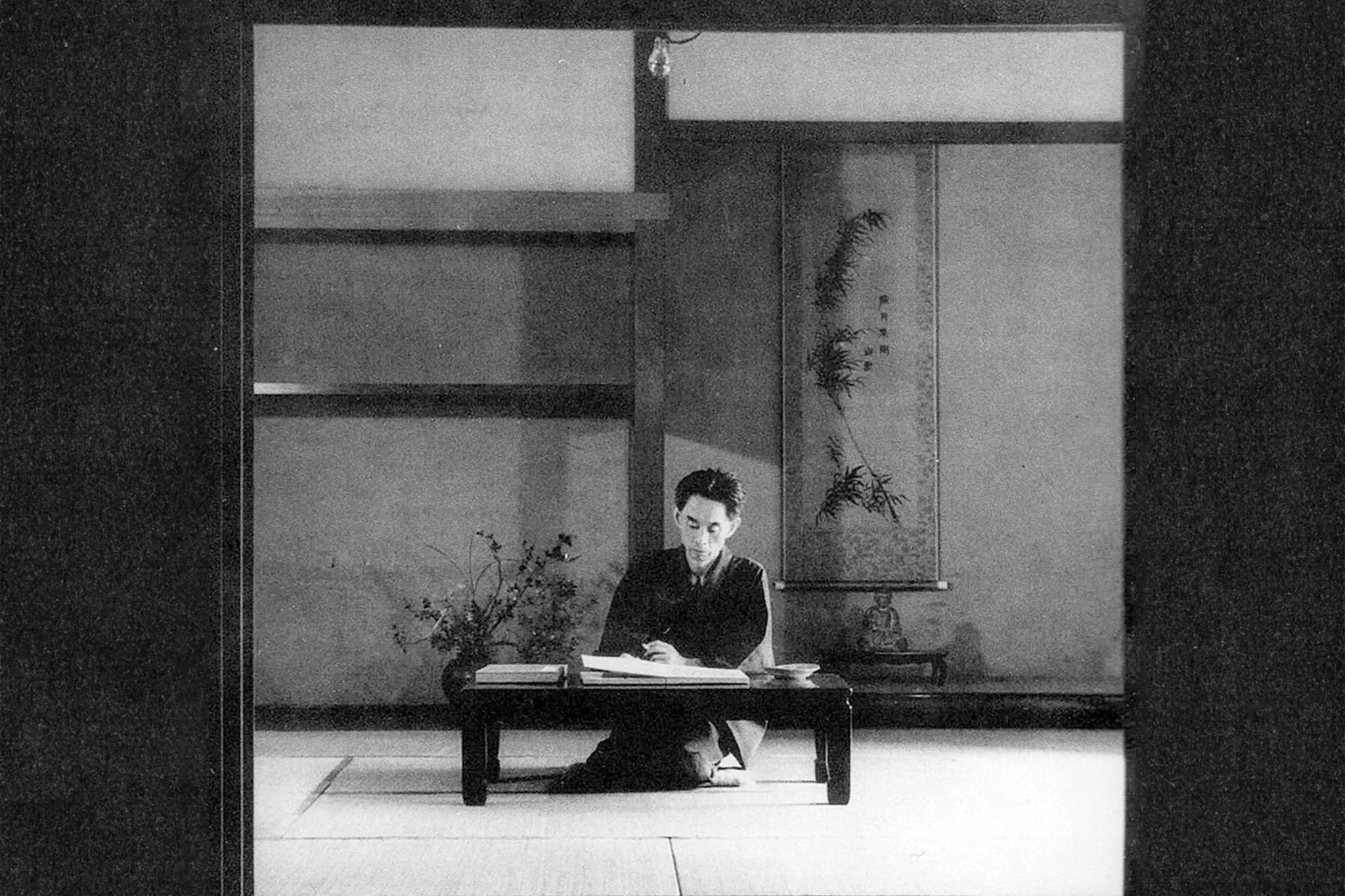

On this day in 1968 came the news that a Japanese author would, for the first time ever, be receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature. That author was, of course, Yasunari Kawabata, a national treasure in this country who was known for masterpieces such as Snow Country and Thousand Cranes. One of the most revered writers of the 20th century, we’re looking back at his life and career for the latest in our Spotlight series.

A Tragic Background

Kawabata’s early years were plagued by tragedy. Two years after he was born, on June 11, 1899, he lost his father to tuberculosis. His mother then died of the same disease a year later. He was subsequently brought up by his grandparents, but his grandmother passed away when he was just 6 and a few years after that, Kawabata became the carer for his bedridden, blind grandfather. This period of his life was the main subject of his autobiographical short story, “Diary of My Sixteenth Year.”

It was clearly a tough time for the teenager as he had nobody else to turn to. Going to school, which he described as “paradise,” was his escape. He would then come home and do what he could for his grandfather, such as cooking for him, turning him over in bed and helping him urinate into a bottle. He would often be called upon in the middle of the night. “It’s not right,” he wrote, “to live so long in this world only moving backward.” When Kawabata was 15, his grandfather died. Despite the difficulties he had caring for him, the death hit him hard.

The sense of despair for Kawabata, who also lost his sister when he was 10, continued during his university days as his first love, Hatsuyo Ito, broke off their engagement. An unsent letter to her was found at his Kamakura apartment. “I cannot sleep at night out of fear you may be sick,” he wrote. “I am so worried that I am starting to cry.” Ito didn’t tell him why she ended their relationship, only saying that she would “rather die” than reveal the truth. It’s believed that she was raped and couldn’t get over the shame.

Snow Country

A Tale of Love, Despair and Fame

“I was a 20-year-old man, and I promised marriage to a 14-year-old,” wrote Kawabata. “Everything was broken senselessly, and I was left deeply wounded. After the Kanto earthquake, I wandered the burned fields of Tokyo because I wanted to make sure she was safe… But that girl no longer exists in this world.” The doomed relationship with Ito had a big influence on his works, particularly his early short stories about Michiko, the fictitious name given to his ex in titles such as “South of the Fire” and “Bonfire.”

Many of Kawabata’s early stories appeared in Bungei Jidai (The Artistic Age), a literary journal he began with Riichi Yokomitsu in 1924. This included “The Dancing Girl of Izu,” the novella that launched his career. He wrote the original draft, then titled “Memories from Yugashima,” in 1922 after escaping from his depressing dormitory life in Tokyo. Published in 1926, it was the first of Kawabata’s works to be translated into English. It’s also been adapted for film and television several times and the Odoriko (meaning “dancing girl”) express train from Tokyo to Izu is named in its honor.

Into his 30s, Kawabata continued to enhance his reputation with novels such as The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa, which portrays the harsh and energetic atmosphere of what was, at the time, one of Tokyo’s shadier regions, and Snow Country, which is widely considered his magnum opus. “The train came out of the long tunnel into the snow country. The earth lay white under the night sky.” These are arguably the most famous opening lines in Japanese literature history. Described as haiku in prose, it’s a work of subtle beauty about an ill-fated affair between a Tokyo dilettante and a local geisha.

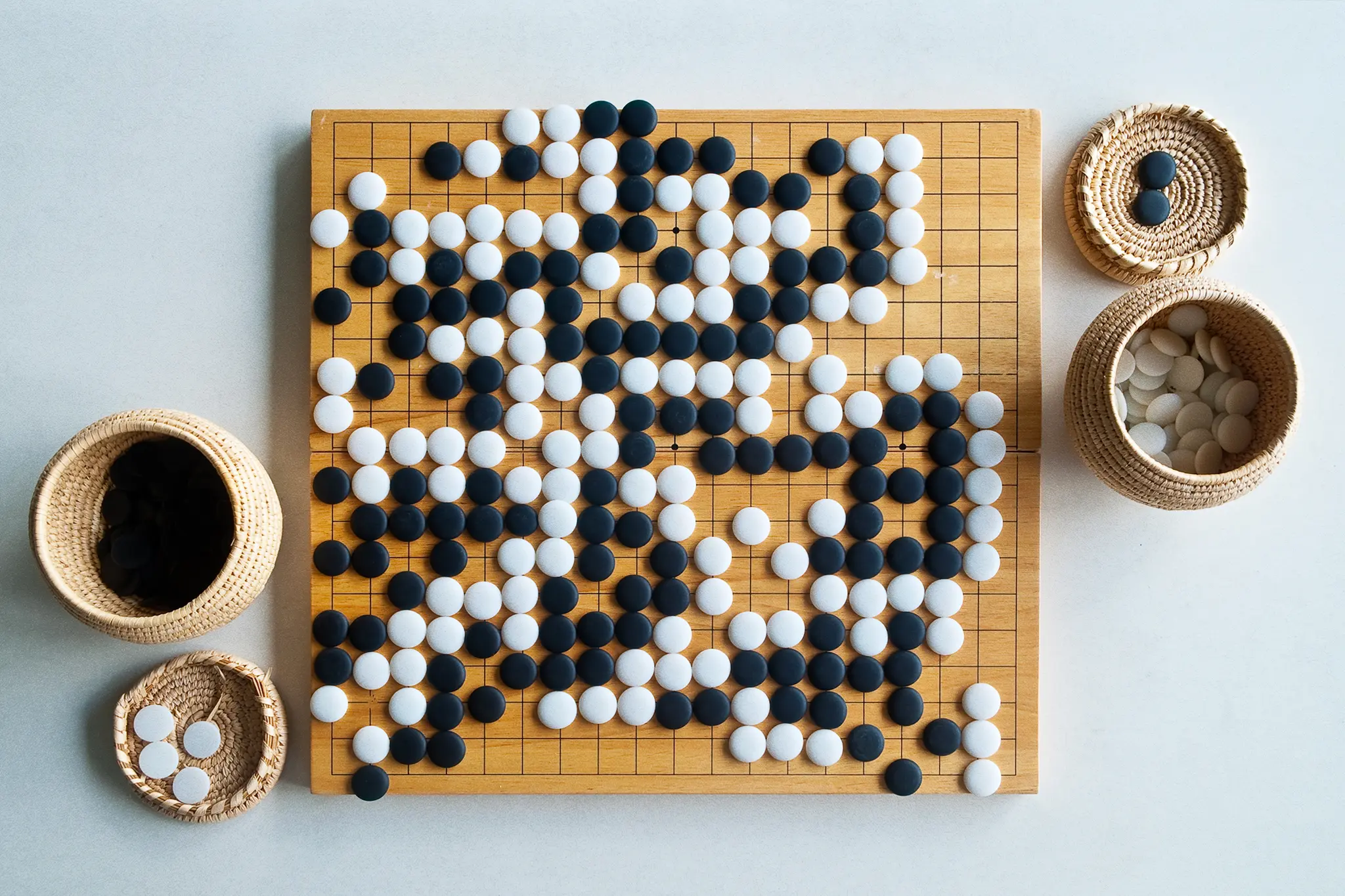

A game of Go | Image by Saran_Poroong via Shutterstock

The Post War Years

While many consider Snow Country Kawabata’s crowning achievement, the man himself regarded The Master of Go as his finest work. Printed in book form in 1954, it’s also the only one of his novels he felt he had completed. The semi-fictional story focuses on the final Go game of the respected master, Honinbo Shusai, as he takes on “the Prodigy,” Minoru Kitani. It lasted almost six months with the young pretender eventually triumphing. According to Kawabata, “the beauty of Japan and the Orient had fled. Everything had become science and regulation.”

Two other standout Kawabata books published in the 1950s (though both initially appeared in serialized form in 1949) were The Sound of the Mountain and Thousand Cranes. The former is a leisurely paced and sensitively written tale about a man coming to terms with aging and his own mortality. The latter, set against the backdrop of a tea ceremony, follows an orphaned businessman and his relationship with his father’s mistress and her daughter. According to Kawabata, it was a “negative work, and an expression of doubt about and warning against the vulgarity into which the tea ceremony has fallen.”

Thousand Cranes and Snow Country were both cited by the Nobel Committee when Kawabata received his literature prize in 1968. The other book mentioned was The Old Capital. First published in 1962, a year after he was awarded the Imperial Order of Culture, it’s a poetic tale set in Kyoto that delicately explores themes such as repressed emotions and changes to traditional Japanese life through the eyes of Chieko, who attempts to discover the truth about her past. There have been three movies based on the novel, the most famous of which was Noboru Nakamura’s Twin Sisters of Kyoto, which was nominated for an Academy Award.

Yukio Mishima

The Final Years

A year before the release of The Old Capital, Kawabata was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature for the first time. Following his eighth successive nomination, he finally got his hands on the award in 1968. There were 76 nominees that year, including Kawabata’s compatriots, Yukio Mishima and Junzaburo Nishiwaki. Among the leading contenders were French novelist André Malraux, British poet W. H. Auden and Irish playwright Samuel Beckett, who won the following year. According to the Nobel Committee, Kawabata received the award “for his narrative mastery, which with great sensibility expresses the essence of the Japanese mind.”

Kawabata picked up the prize alongside his translator Edward Seidensticker. He said he could never have won without the American’s excellent translations. In his Nobel lecture titled “Japan, the Beautiful and Myself,” Kawabata touched on several topics such as tea ceremonies and Zen Buddhism, but it was the part about suicide that stood out the most. Quoting his own essay, he said, “However alienated one may be from the world, suicide is not a form of enlightenment. However admirable he may be, the man who commits suicide is far from the realm of the saint.”

Two years later, his protégé, Yukio Mishima, famously took his own life. Kawabata struggled to come to terms with this news and allegedly had recurring nightmares that featured his fellow author. Not long after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Kawabata, too, according to reports, committed suicide on April 16, 1972. He was said to have gassed himself, though those closest to him, including his widow, Hideko, believed his death was an accident. He was 72. His books live on, though, and have been translated into several languages. A hugely influential figure, he will forever be remembered as Japan’s first Nobel laureate in Literature.