Sitting across from multiple child sex offender Takashi Kato, filmmaker Sybilla Patrizia admits she felt somewhat uncomfortable. This was, after all, a man who abused at least 11 minors over a 24-year period. “On the one hand, I couldn’t believe I was in the same room as someone like that,” recalls Patrizia. “On the other, I had a job to do and that’s something I take very seriously. I want to tackle controversial topics and that, at times, means meeting people I completely disagree with or am even appalled by.”

The Tokyo-based Austrian director was filming a short documentary for Vice News Tonight titled The Dark Side of Manga (originally called Inside the Pedophilic Manga Industry in Japan). Presented by American journalist Hanako Montgomery, the 16-minute video explores the effects that sexual images of minors in cartoons can have on society and questions where we should draw the line when it comes to freedom of expression. The film won a News & Documentary Emmy award last year for Outstanding Arts, Culture or Entertainment Coverage.

Exploring Gray Areas

“I’m drawn to stories that are challenging, and this one certainly was,” Patrizia tells TW. “While it’s obviously a dark topic that was difficult to do, I think it’s so important to explore gray areas as a documentary filmmaker, even if it leads to criticism. There was a big backlash from manga and anime fans online who felt we were trying to bash these industries. That wasn’t our intention at all. Manga and anime can be incredibly beautiful, but we wanted to show a part of this media that is controversial and we feel we should be talking about. I believe we did it in a transparent way and listened to both sides of the argument.”

The first person Montgomery introduces viewers to in the documentary is an anime super fan and manga artist known simply as Shinji. He shows a story he’s written for a BDSM comic about a young girl who is raped. He admits to being attracted to minors and, later in the film, says he feels guilty about his drawings but also believes this kind of work “prevents pedophiles from abusing kids by allowing them to live out their dark fantasies alone.” In his opinion, you “can’t force someone to stop just because you are disgusted. And you can’t create laws just because of personal objections.”

Politician and manga artist Minoru Ogino agrees. Asked about the potential link between child sexual abuse images in manga and sexual abuse, he responded by stating, “There is no evidence that this material leads criminals to their acts. When the state thinks about laws or regulation, there has to be a scientific basis.” Kazuna Kanajiri, however, sees things differently. Chief director of PAPS, the Organization for Pornography and Sexual Exploitation Survivors, she believes these kinds of illustrations condone “child grooming and child abuse” while also normalizing the idea of children having sex with adults.

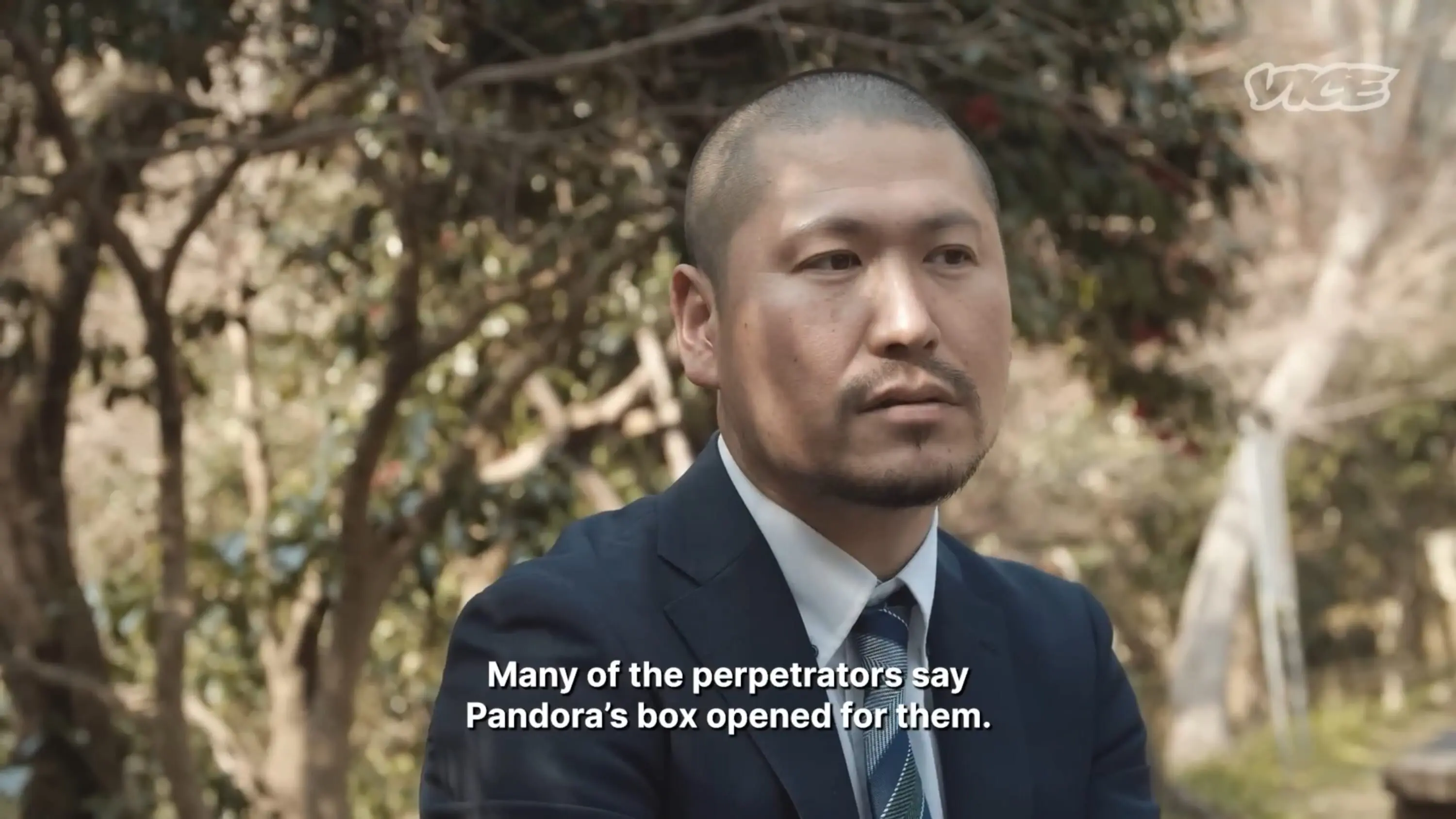

Tokyo-based mental health care worker Akiyoshi Saito, who’s treated over 150 sex offenders, claims that 90% of his patients have viewed child sexual abuse images in manga, with many of them telling him the images “opened a Pandora’s box.” One man who went for sessions with Saito was Kato. He agreed to appear in the documentary because he doesn’t want young people repeating his horrific mistakes. “There was a manga that depicted sexual abuse of young children. That very quickly became my whole sexual world,” Kato tells Montgomery. “I started reading these manga often, and more and more my desire to sexually assault children increased.” His first victim was aged between 3 and 4. Many more would follow before he eventually turned himself in to the police.

A Mental Transformation

“At first glance, he seemed very fragile and vulnerable — not at all like what I imagined a sexual predator to be,” says Patrizia. “What he did in the past was truly awful, but we must do more than just point the finger and say he’s bad. We need to ask why people like this commit these kinds of crimes. A lot of abusers, for instance, were abused themselves. Society isn’t there to help them, so then it becomes a vicious cycle. Victims of sexual abuse sometimes feel they can’t come forward to get help and are subsequently unable to move on with their lives. It’s our responsibility to provide a better support system.

“I went through a mental transformation making this documentary,” continues Patrizia. “Seeing those images of kids getting abused, it was the first time I’d ever felt sick reading a book. Yet, at the same time, they’re just illustrations and not real children. Also, we don’t have any clear studies that show whether this kind of material increases or lowers crime. Just because I find it disgusting and disagree with it personally, does that give me the right to stop people drawing it or reading it? No matter where you align yourself, it’s important to really look at the situation, listen to everybody, then form your opinion, rather than judging too quickly.”

The film, which hasn’t been shown in this country, caused quite a stir online, with a real mix of positive and negative feedback. Patrizia is grateful to Vice for tackling such a controversial topic, as she feels there wouldn’t be many companies in Japan prepared to take on such a story. In her opinion, young documentary filmmakers don’t have much of a voice in the Japanese media industry. She believes the system is controlled by a few gatekeepers with connections to specific broadcasters.

Endless Stories

“I remember holding the Emmy award thinking how surreal it was what our small team had achieved, yet it wouldn’t have been possible without the backing of a major publication like Vice,” opines Patrizia. “Most documentary filmmakers don’t have that kind of opportunity. I’d love to help create a support system here, so more voices are heard. People want more than your typical broadcasting coverage. They’re craving content that matters to them. Japan has endless stories we can tap into. The difficulty is getting them out there.”

Patrizia experienced this firsthand with her documentary short A Bloody Taboo about the stigma against menstruation in Japan. Despite winning the Excellent Film Award at Tokyo Docs, every distributor turned the film down because it was deemed too controversial. Eventually, she found one that was prepared to distribute it — until that company decided it didn’t want to show blood on screen. Fortunately, it took on a life of its own through social media and was shown at the University of Tokyo and by some non-governmental organizations.

A more recent project for Patrizia is Plastic Love! Her first feature-length film, it deals with Japan’s over-consumption of plastic. People, she feels, are preoccupied with false solutions like recycling and bioplastics rather than focusing on real ones such as zero waste practices, producer responsibility and tackling mass consumption. Currently in post-production, she’s trying to find funding to finish the project.

She’s also been working on her second feature-length documentary, The Shape of Blue, which picked up the Best Pitch Award at Tokyo Docs 2023. Exploring what color means for humans, it focuses on indigo dyeing in Tokushima Prefecture. After a 10-minute screening next year, it will eventually be turned into something much longer.

More Info

Get the latest on Patrizia’s projects via her website at sybillapatrizia.com and on Instagram at @sybillapatrizia.