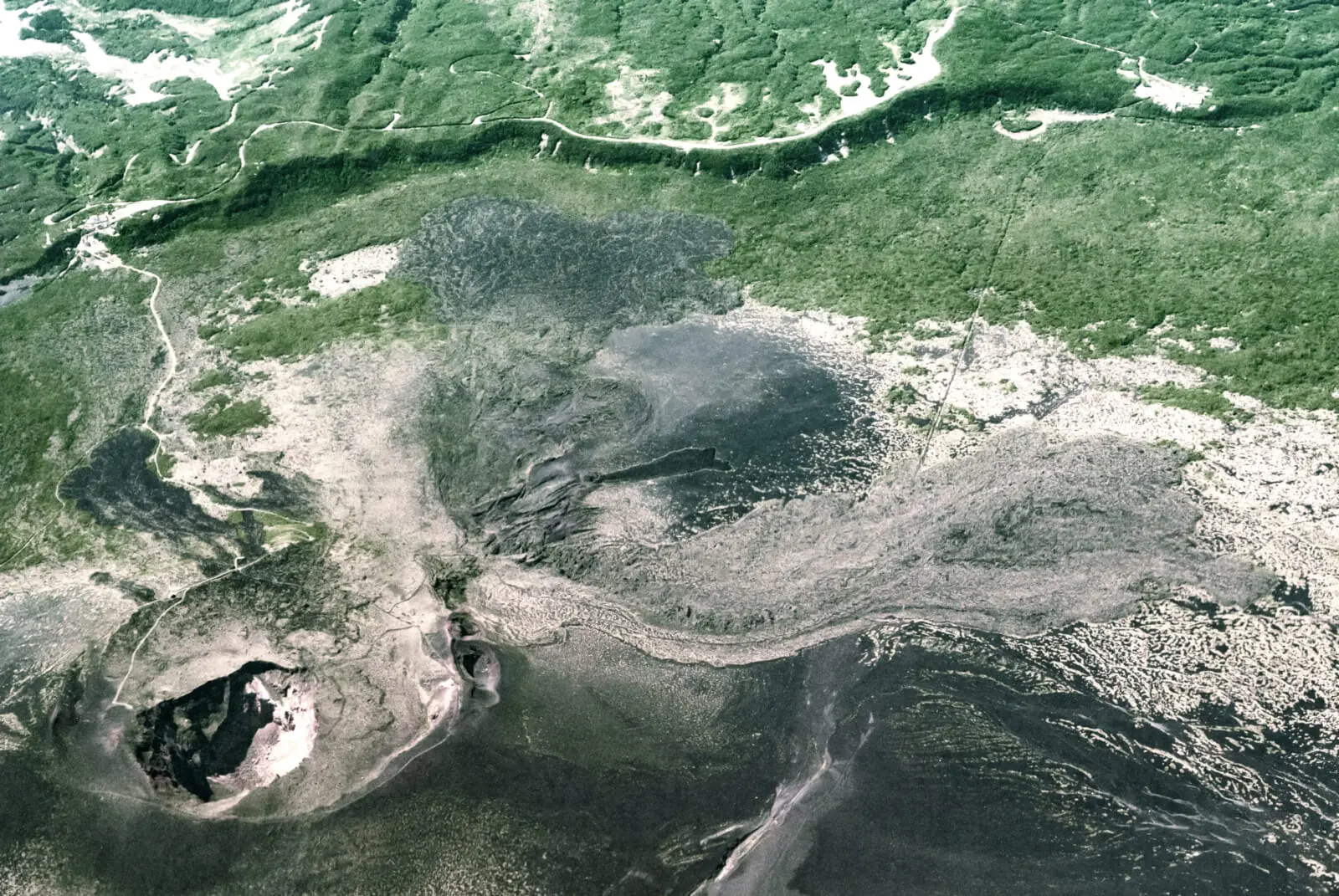

Mount Mihara is an active volcano on Oshima Island, located east of the Izu Peninsula in Shizuoka Prefecture. It’s said to erupt every 100 to 150 years, and it did so in 1986, spewing lava everywhere and leaving behind a 16-kilometer-tall plume of smoke, forcing every person on the island to evacuate. Since it was pretty recent, we don’t have to worry about another eruption for a few more decades.

However, if Oshima’s century-long cycle applies to all kinds of blowing up, then we may have a problem in a few years, because in the 1930s, another thing exploded on the island: the number of people committing suicide by throwing themselves into the volcano. And it apparently all started with one lesbian killing herself. That’s the short version anyway. Here’s the long one.

Aerial view of Mount Mihara

From ‘Same-Sex Lover’ to ‘Death Guide’

On February 12, 1933, Kiyoko Matsumoto, a 21-year-old second-year student at a prestigious Tokyo women’s university, threw herself into the Mount Mihara volcano, allegedly because of her forbidden love for her classmate Masako Tomita. It was supposedly meant to be a lovers’ double suicide, but Tomita was stopped by a guard at the last minute and survived.

When the papers caught wind of it and found out that Matsumoto was obsessed with poetry and literature, it felt like Christmas in newsrooms across Japan. The headlines basically wrote themselves and focused heavily on the same-sex romance from every possible angle.

Their love was “beautifully tragic,” said some papers. “Lesbianism is killing our children,” lamented others. Some publications, not wanting to waste a good frenzy, also blamed Matsumoto’s suicide on her obsession with poetry and books.

It then came out that the miraculously saved Tomita actually had a return ferry ticket with her and that she had accompanied another suicidal student to Mihara a month prior. The narrative subsequently changed.

Suddenly, Tomita was cast in the role of a villain. An evil-minded, psychopathic “death guide” who facilitated the deaths of two young women. Of course, the newspapers continued to stick with the whole “lesbian” angle because clickbaiting existed long before the internet.

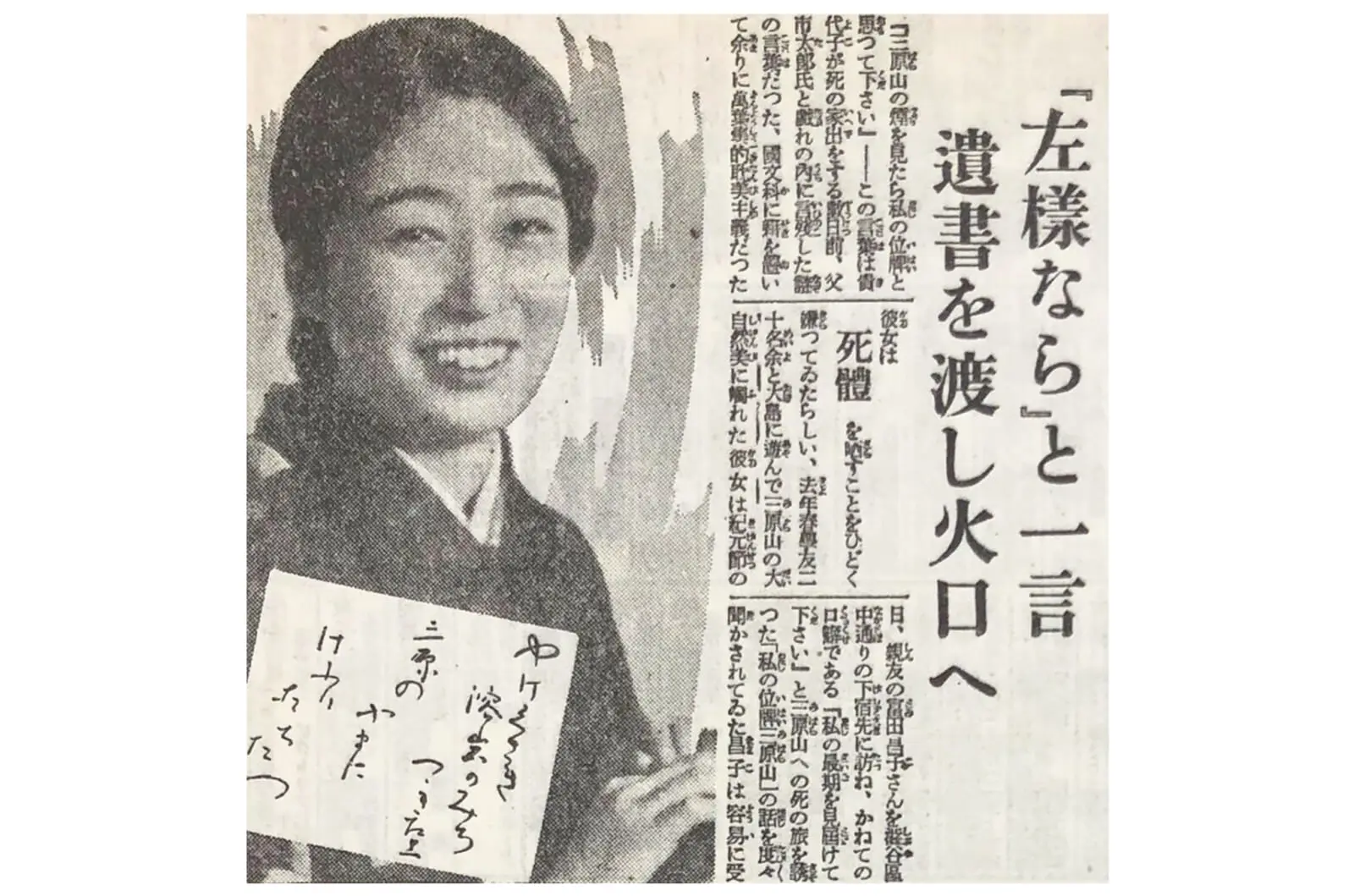

Asahi Shimbun Newspaper Clipping of Kiyoko Matsumoto’s Final Words, February 15, 1933.

Fuzzy Records

Tomita was never charged with anything, but intentionally or not, her role in Matsumoto’s suicide did indirectly lead to hundreds of deaths. The story took Japan by storm and in 1933, there were 129 copycat suicides by volcano on Oshima Island and over 600 attempts.

Barriers and more guards were erected but that didn’t seem to help. The Pennsylvanian paper Reading Eagle reported that 619 Mihara suicides occurred in 1936, with a total of 2,000 in the span of six years, though those numbers are suspect.

The exact records are fuzzy, but the Matsumoto-inspired suicides were real. And weirdly flippant. Matsumoto left behind a poem conforming to the created narrative of an emotionally-wrecked virgin intoxicated by a love that could never be.

Those who followed her, though, came from all walks of life: straight couples, blue-collar workers and the elderly, for instance. And they didn’t leave any poems behind. Many of the copycat suicides were performed in broad daylight because the soon-departed wanted an audience. They reportedly really hammed it up in their final moments, with some doing acrobatic jumps and others swan-diving into the lava.

Kiyoko Matsumoto’s Final Words

Not everyone has the chance to leave behind final words. Matsumoto left several but most don’t really help us understand why she ended her life. On the day she headed to Oshima Island, her final words to her father were “Like a cloud.” According to Tomita, Matsumoto only said that it was her time to die while climbing Mount Mihara.

She did leave two notes behind. The one addressed to a close friend only included a poem by the 9th-century courtier Ariwara no Narihira that seemed to hint at forbidden love. Maybe. But it was Matsumoto’s last note that was the most informative.

It was addressed to the friend’s mother and said: “I will kill the person I hate the most, the person I am, because it seems to be the best thing I can do for the me on the other side.”

The content isn’t really as important as the recipient of the note. Kirsten Cather, an associate professor in the Asian Studies department at the University of Texas at Austin, brings up the fact that Matsumoto’s own mother died when she was young and that her addressing a suicide note to another mother she was close with could mean something.

Matsumoto also lost an older sister in 1932. Her suicide, therefore, might have been driven by feelings of loss and loneliness. Does it mean that she wasn’t gay? We don’t know. Maybe she was, maybe she wasn’t. It’s all speculation. So let’s talk a bit about the facts.

Understanding Suicide in Japan

Suicide isn’t encouraged in Japan or anything like that, but there also hasn’t exactly been a taboo against it, historically speaking. If anything, dying on your own terms has for centuries been seen as a means of retaining one’s honor, which is how harakiri and seppuku came about.

Double suicides between star-crossed lovers — known as shinju — were especially romanticized during the Edo Period. So much so that Hiraga Gennai, the 18th-century Japanese equivalent of Leonardo da Vinci, tired of shinju tropes, penned a parody titled A Lousy Journey of Love in which two lice travel down a body to commit suicide, stopping along the way at the Temple of the Saint Anus and ultimately arriving at Hotel Testicle.

Making fun of the trend, however, did little to stop it and suicides (single and double) continued to be prevalent in Japan. Before Matsumoto, there was the 16-year-old poet Misao Fujimura, who killed himself in 1903 at the famous Kegon Falls in Nikko, which also attracted copycats.

After Mihara, there was the 1960 novel by Seicho Matsumoto (no relation), called Kuroi Jukai (Black Sea of Trees), which is credited with popularizing the Aokigahara Forest at the foot of Mount Fuji as a good place to kill oneself because of how isolated it is.

People are still killing themselves at Aokigahara, with regular sweeps of the forest by authorities often discovering hanged bodies. It remains one of the most popular jisatsu meisho (suicide sites) in Japan. The fact that the country has a special word for them tells us a lot about the state of the problem over here.

In the end, Matsumoto’s death remains a tragedy that can’t be explained by one thing, like forbidden love, poems or even depression. Suicide is complicated. Her death could have been a combination of many factors, some of which we might never know. The best thing we can do is to acknowledge that and stop guessing. Because that is a game with no winners.

If you’ve been having suicidal thoughts or know someone who has, help is available via the TELL Lifeline.