The idea of Japan’s “warrior monks” has an undeniable appeal to it. It instantly conjures up a lot of romantic images of warriors in Buddhist garb fighting evil with the power of their faith. It’s religion with some teeth … and fists, kicks, blades, etc. It’s also a kind of weird fetishization.

First, Japan isn’t the only place with warrior monks. The European Teutonic Knights and the Knights Templar, for example, were both monastic orders of holy warriors with vows of chastity, poverty and obedience. They were warrior monks as much as their Buddhist counterparts, the latter of which, incidentally, had an ignoble beginning and a sadly pitiful ending. The middle part was cool, though. Let’s talk about them all.

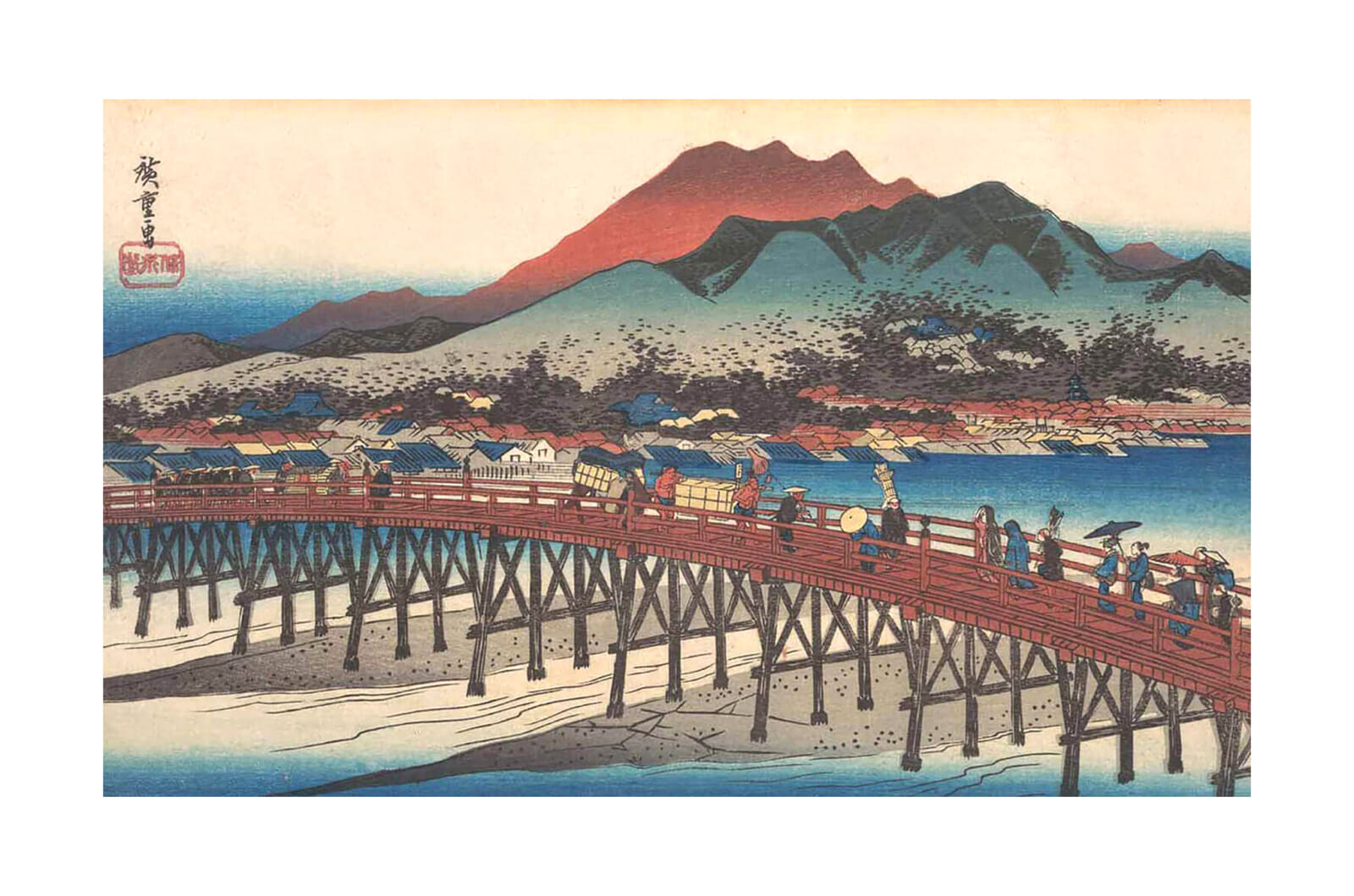

Mount Hiei in the background of “Sanjo Bridge” by Utagawa Hiroshige (1833)

Warrior Monks Were Created To Fight Other Monks

The history of Japanese warrior monks begins with the moving of the capital to Kyoto in 794. Based on the principles of feng shui, one of the most crucial parts of the city was a mountain in the north to protect it from evil energies. That mountain was Mount Hiei, occupied by the massive Enryaku-ji temple complex. Suddenly finding themselves the spiritual protectors of the imperial court, Enryaku-ji’s stock skyrocketed while taking some prestige away from the Todai-ji and Kofuku-ji temples in Nara. They didn’t take it well.

From around the 10th century, tensions between temples started erupting into brawls that occasionally ended in death. Most of the disputes were about land or abbot appointments. After one fight too many, Ryogen, the abbot of Enryaku-ji, decided to keep a permanent fighting force on Mount Hiei in 970. These warriors weren’t monks, though; they were more like private security made up of laymen. However, over the years, many ordained men joined their ranks in fights against their fellow ordained men. But they were from different temples or branches of Buddhism, so it was OK to unleash great violence upon them.

Between the 10th and 12th centuries, Enryaku-ji, Todai-ji, Kofuku-ji and Onjo-ji (also known as Miidera) were constantly attacking each other. The monks of Mount Hiei burned down Miidera at least four times. Ever so slowly, all this fighting taught the Buddhist monks the art of war. They would soon have a chance to test it out on the battlefield. The results were … mixed.

The skulls of his slain enemies haunted Taira no Kiyomori later in life. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1883)

Warrior Monks Briefly Get a Head…or 60

In 1180, the Genpei War erupted between the powerful Taira and Minamoto clans. Deciding to shelter a prince supported by the Minamoto, Miidera entered the war, fighting bravely and awesomely during the Battle of Uji. One monk in particular, Gochi-in no Tajima, is said to have used his naginata glaive to cut arrows flying directly at him, earning the nickname “Tajima the Arrow-Cutter.” In the end, though, Miidera’s side lost the battle, and the Taira army destroyed the temple. Later, after the monks of Kofuku-ji killed a delegation of Taira Kiyomori, displaying 60 of their decapitated heads around Sarusawa Pond, Kiyomori ordered Nara to be burned to the ground as revenge. After that, Enryaku-ji meekly stayed out of the conflict.

The following years weren’t great for the reputation of warrior monks. The capital was moved from Kyoto to Kamakura, and Mount Hiei soon discovered that, unlike the old Kyoto nobility, the samurai weren’t afraid of them. They also practiced Zen Buddhism, a totally different school than any of the warrior monk centers, so their curses and condemnations meant nothing to them. Even after the shogunate relocated to Kyoto in the 14th century, the monks of Mount Hiei weren’t taken seriously by samurai. Then, suddenly, the imperial and samurai governments collapsed, and the country entered an era of two centuries of civil war. This was a Buddha-send to the warrior monks.

japan’s warrior monks

Warrior Monks vs. the Demon King

During the Sengoku period, the warrior monks flourished. Utilizing their organizational skills, religious symbolism and proficiency with all sorts of weapons (including firearms), Japan’s holy warriors became a force to be reckoned with. Feudal lords outbid each other to gain the favor of warrior monks, especially the Mount Hiei ones, who eventually allied with the powerful Asai and Asakura, hoping to help one of them take the throne or the shogunate.

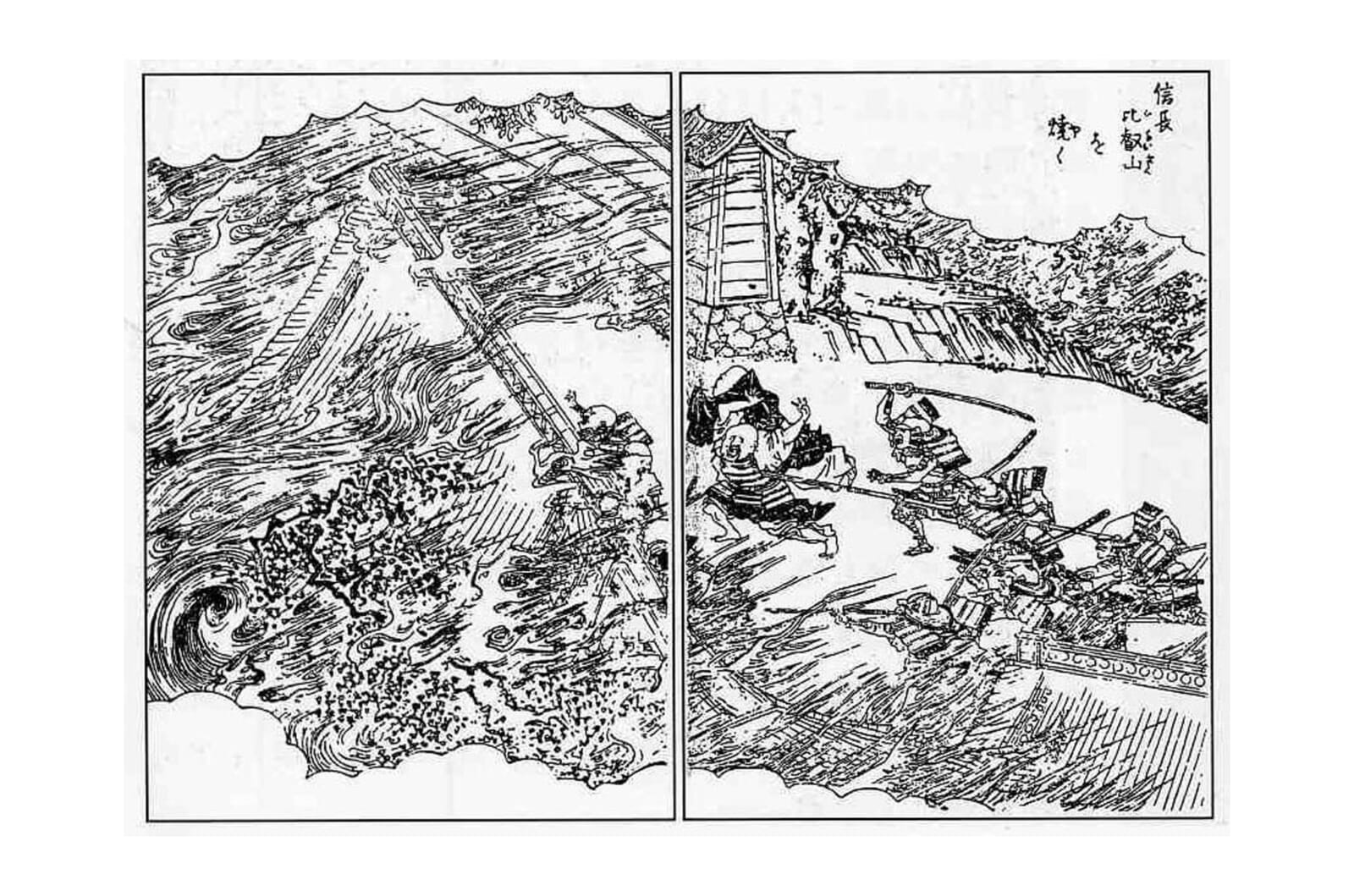

The problem was that both families were enemies of Oda Nobunaga, one of the greatest military leaders in Japanese history and the man who kickstarted the unification of Japan. He warned the Enryaku-ji monks to stay out of his way and not assist his rivals. They did not listen. So, on September 29, 1571, Nobunaga earned his “Demon King” nickname. He had 30,000 troops surround Mount Hiei and then move up, destroying and killing everything in their path. In the end, 20,000 people were killed, including monks, temple workers, women and children. This ended organized armies of warrior monks in Japan, and the reason it all happened so fast was because Enryaku-ji had no defenses.

Enryaku-ji relied primarily on the terrain and its status as the spiritual guardian of Kyoto to protect itself. Todai-ji and Kofuku-ji were similarly open targets. It was the Ikko-Ikki — peasant Buddhist fanatics led by warrior monks — who actually built religious fortresses. Just ONE of them kept Nobunaga occupied for 10 years, thanks to the efforts of the monk who could’ve been shogun. Maybe if Enryaku-ji had followed the Ikko-Ikki’s example, its end wouldn’t have been so … anticlimactic.

So, Hey — Is It All Right To Call Warrior Monks Sohei?

Sohei is a popular term for Japanese warrior monks in both Western and Japanese sources, but for some years now, there’s been a debate over its accuracy. The term literally translates to “priest soldier” and seems like an accurate description of the monks who decapitated 60 people or cut arrows in mid-flight. But, as we mentioned before, the first temple warriors were not monks or priests, and while that changed over time, it was still common for monasteries to recruit warriors who took Buddhist vows but did not live as monks. They were essentially “ringers” hired before big brawls.

Being a part of a Japanese monastery had its perks, like protecting you from the law by absolving you of past crimes. All you had to do was say a few words that you didn’t have to believe in, put on a monk robe and armor, and do what you did best: fight and kill. Then you could go drink and have sex. These people were a significant part of monastic armies, but it feels inaccurate to call them sohei.

And what about samurai commanders who were ordained as Buddhist priests or monks, like Takeda Shingen or Uesugi Kenshin? Were THEY sohei? Does it matter that the monks themselves didn’t use the term? Their enemies called them akuso (evil monks), though. Where does that fit in? There most definitely were people whom you could call sohei, but it’s a very narrow definition that has been used too broadly in the past.

“Monastic warrior” seems like the safest term because it applies to everyone who fought professionally for a temple, whether they lived like a monk or not. But “warrior monk” simply sounds cooler, so that’s what we ultimately went with.

Sources:

Japanese Warrior Monks AD 949 – 1603, Stephen Turnbull

The Gates of Power, Mikael Adolphson

The Tale of the Heike, translated by Royall Tyler

The Teeth and Claws of the Buddha, Mikael Adolphson