Hozoin In’ei got his name from a branch of the prestigious Kofukuji temple in Nara, known as one of the old centers for warrior monks. Despite that, he never saw battle, and in his autumn years rejected all violence. Yet his life-long obsession with martial arts helped him invent a new weapon that was so versatile and deadly that it has outlived its creator by more than four centuries and counting.

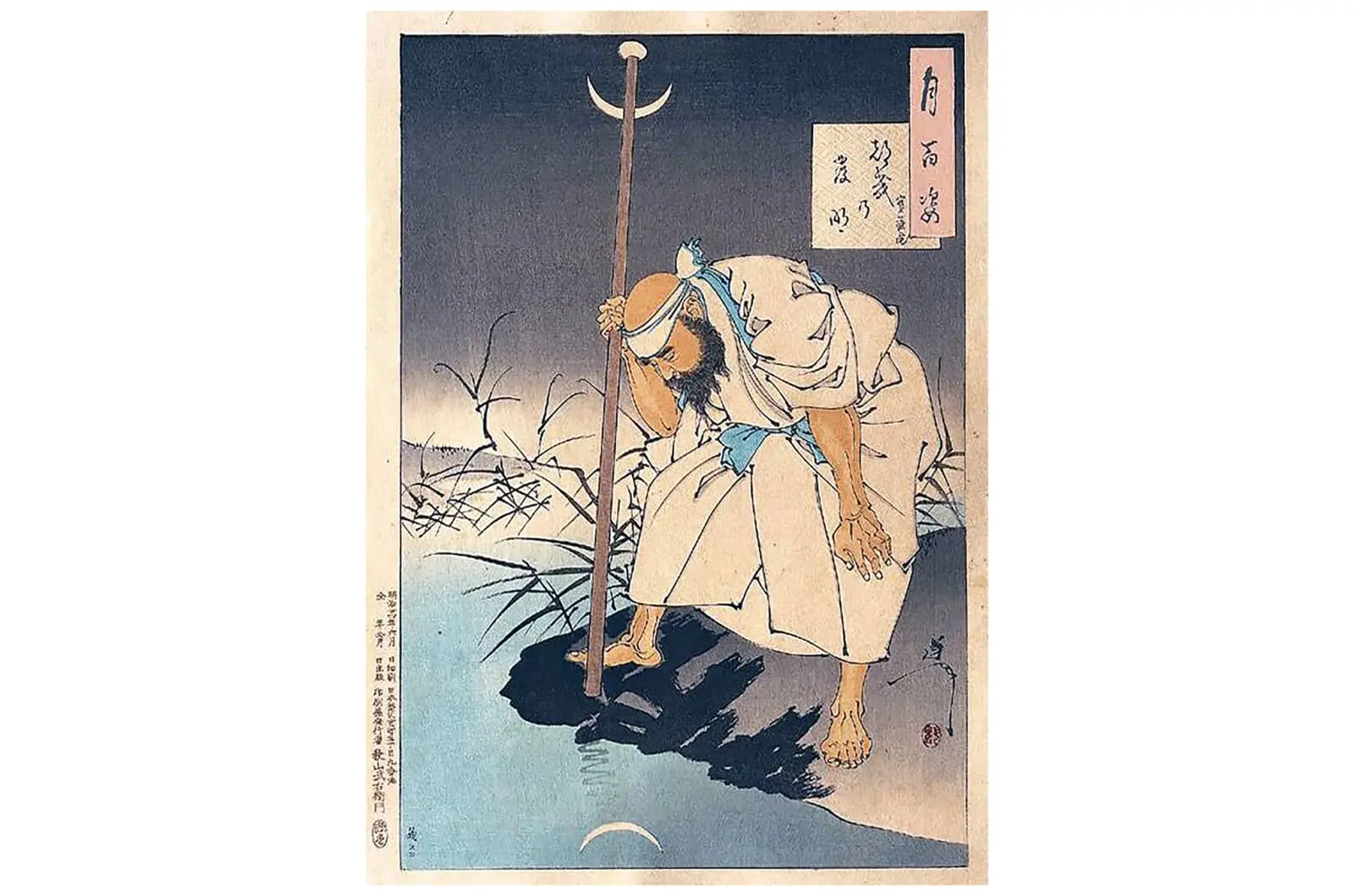

Hozoin In’ei in “Inventions of the Moon” by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1892)

When the Moon Hits Your Spear, That’s a New Weapon My Dear

In’ei, the son of a warrior monk, adored martial arts from a young age and throughout his life had more than 40 teachers training him how to use weapons. With their help, he mastered the sword, the naginata and the spear.

Then one night, something interesting happened when he was practicing his sojutsu (the art of the spear) near Sarusawa Pond. It was the same pond where the monks of Kofukuji decapitated 60 samurai and placed their heads around the body of water. If any place was spiritually primed to become the birthplace of a new type of deadly weapon, it was the Sarusawa Pond.

Legend goes that, during his training, In’ei saw a reflection of the crescent moon on the water, which merged with the reflection of his weapon and gave him the idea of adding a crescent-shaped blade to his spear. And thus, the kama yari (sickle-spear), also known as the jumonji yari (cross-shaped spear), was born. Its timing could not have been better.

The Age of the Spear

During the Sengoku period, when both the imperial and military governments lost all authority and powerful feudal lords fought for dominion over Japan, spears became one of the most sought-after weapons in the country. It all started with the rise of the ashigaru foot soldiers in private armies, who were thrown at the enemy in large numbers and thus needed effective weapons that could be mass-produced on the cheap. Spears and pikes were the obvious solution.

The samurai quickly followed their examples. They, of course, had been practicing sojutsu long before the ashigaru even existed, but seeing the effectiveness of the weapon in large-scale battles inspired them to take their own spears out of storage and put them into action.

Full-blown spear mania soon spread in Japan. After battles, commanders started identifying the seven most valuable samurai and distinguishing them as the Shichi Hon Yari, or Seven Spears. Also, the samurai who first made contact with the enemy was recognized as the Ichiban Yari, or First Spear.

A Spear for All Seasons

As the Sengoku period went on, the use of pikes and firearms made mounted and cavalry charges less commonplace. The kama yari was born for these occasions. Thanks to its horizontal blade, In’ei’s invention was great for hooking samurai and pulling them down from horses, stopping their weapons at a safe distance from the users. It also allowed them to slash as well as thrust.

Crescent spears apparently even found use outside battlefields, with firefighters using them to pull down roofs off houses to stop the spread of town fires. But this probably only happened after In’ei’s death.

The versatility of the kama yari supposedly led to this description found in a poem: “A spear when you thrust, a naginata when you cleave, a sickle when you slash. In any case, it never misses the target.” Truly, the Swiss Army knife of its day.

Miyamoto Musashi Finally Makes an Appearance

The Kofukuji and Hozoin monks didn’t actually do much during the Sengoku period. They still remembered the 60 decapitated heads incident, which ended with all of Nara being burned down in retaliation. So In’ei’s fascination with weapons was really more about exercise. He never actually went out and tested the kama yari in battle.

What’s more, in 1585, when the local lord ordered the people of his province to surrender all weapons and cease martial arts training, In’ei obeyed. The only reason his style of sojutsu, known as Hozoin-ryu, didn’t die out there and then was because an influential samurai wanted some spear lessons for his son, resurrecting the temple’s weapons program.

Not long after that, in 1604, the already-renowned warrior Miyamoto Musashi visited In’ei to challenge him to a fight. He was, however, too late. The monk was 84 years old at the time and his successor, Inshun, was too young to fight in his place, so the honor of battling Musashi went to the school’s top student: Okuzoin Doei.

Despite using a short wooden sword — a weapon seemingly made for the sole purpose of losing to a kama yari — Musashi was able to penetrate the spear’s defenses and defeated Okuzoin in two rounds, forever winning the warrior’s admiration. This incident was later immortalized — in a slightly embellished form— in Takehiko Inoue’s manga Vagabond.

Saved From Oblivion

Before he passed away, In’ei ordered the end to all Hozoin-ryu training because he believed that monks should not focus their energies on fighting. His successors halfway honored that wish. They kept teaching his style of sojutsu at the monastery for a while.

Eventually, though, the three best students were chosen to go to Edo (modern-day Tokyo) to start a secular school of Hozoin-ryu, which didn’t teach monks to fight.

The school was a success and soon Hozoin-ryu masters were employed by the Tokugawa shogunate as teachers up until the abolition of the feudal system when Hozoin-ryu was almost lost again. But it found its way back and survived to this day, thriving nowadays as a sport. For a pacifist, In’ei sure created one resilient weapon and fighting system.