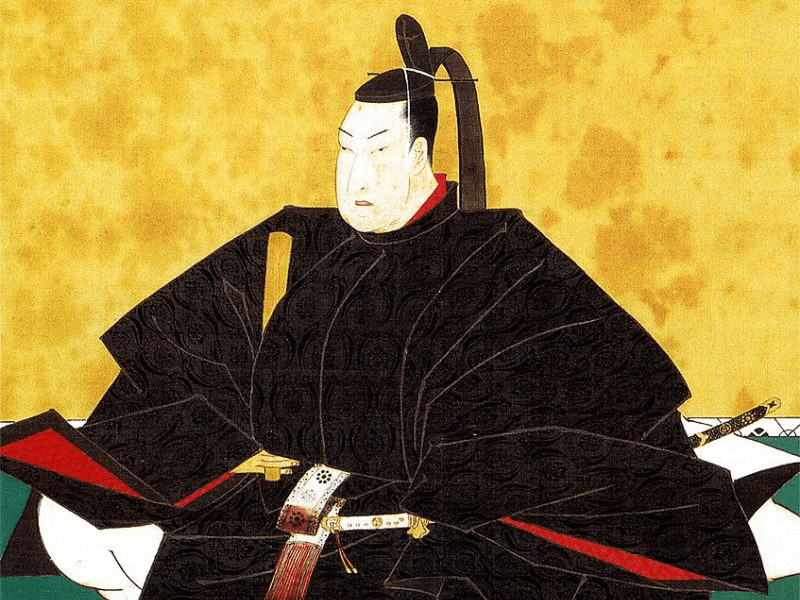

One upon a time, during the Edo period, there was a shogun named Tsunayoshi Tokugawa. For a long time he was maligned by historians, as they based their research on scathing accounts by the samurai class, who didn’t like him much. One of their many complaints was his penchant for young men of any class (it was the lack of his particularity about class rank, not his choice of gender in sexual partners, that irked people most). He was also known to be a bit of a momma’s boy, and, perhaps most famously, he was known for his love of dogs.

Often fondly referred to as Oinusama (the dog shogun), Tsunayoshi really did have a soft spot for man’s best friend. He became immersed in Neo-Confucianism and studied it profusely. Through this influence, he enacted many protections for living beings — not just dogs — during his rule. In fact, he also insisted abandoned children and sick travelers should be taken care of and not be left to die like dogs.

It’s a Dog’s Life

The Dog Shogun was also influenced by the fact that he was born during the Year of the Dog, and he was told he had been a dog in a previous life. He felt responsible for other beings and issued a number of edicts, known as Edicts on Compassion for Living Things, that were released daily to the public. Most of them involved the protection of dogs — in fact, it was a capital crime to harm one. While this was mostly a good thing — old Edo was riddled with diseased stray dogs — eventually there were so many dogs in Edo that historical accounts claim that the city smelled horribly. (Although with poor sanitation at the time, it seems unfair to only blame the dogs for foul smells that spread across the city.)

Eventually, over 50,000 pooches were sent to the city suburbs to kennels, where they were fed dried fish and rice (and presumably given the odd scratch behind the ear) — all funded by Edo taxpayers.

Every Dog Has His Day

Tsunayoshi’s animal-friendly spirit lives on today here in modern Tokyo. At Ichigaya Kamegaoka Hachimangu shrine, dogs and other pets (think hamsters, iguanas and more!) can receive a Shichi-Go-San ceremony. Though it may seem odd, the shrine priests argue that it’s a natural transition — as fewer people have children, more pets become a part of people’s families — and they too, deserve to be celebrated for the joy they bring to their owners. The shrine also offer pet-friendly hatsumode events and have pet-oriented omamori charms among their many pet-friendly services. (Note that most services that involve a visit to the shrine require reservation. See the shrine’s website for more information.)