Many samurai of Japan’s civil-war era tended to be born, live and die the same way: covered in blood and screaming. Even those who made it to old age rarely brought their sanity with them to the finish line. Tsukahara Bokuden was a rare exception.

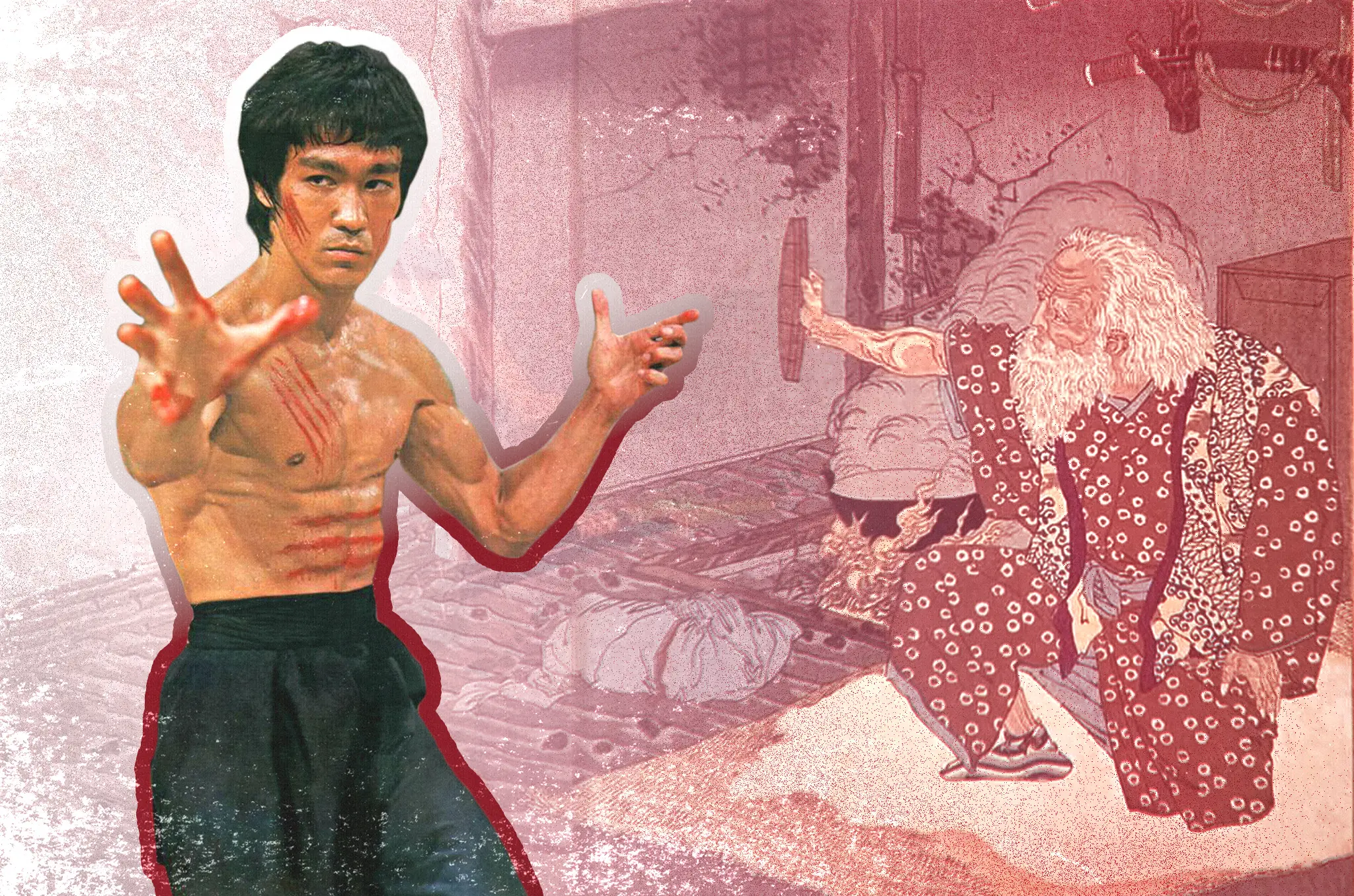

Historical accounts say he passed away peacefully aged 83 after a lifetime of duels and fights that he often won with less screaming and with more calculated tactics, leaving behind a mountain of corpses and a legacy that earned him the title of kensei (sword saint). He even found time along the way to inspire legendary martial artist Bruce Lee. This is his story.

Looking for Trouble in All the Right Places

Born in modern-day Ibaraki Prefecture to the Yoshikawa family, Bokuden was originally destined to become a Shinto priest until the heir apparent of the Tsukahara family — whom the Yoshikawa served — unexpectedly died. Adopting Bokuden as their heir, the Tsukahara family trained the boy to be a swordsman.

This wasn’t a dramatic shift for him. Whether priest or warrior, both paths ultimately sought to bring people closer to the divine. Bokuden had already practiced swordsmanship as a member of the Yoshikawa family, but joining the Tsukahara clan exposed him to advanced techniques, and by the time he was just 17, he was already a master of two styles.

Embarking on a journey across Japan, Bokuden sought to learn new techniques and face stronger opponents. Over time, his legend grew. By some estimates, he participated in nearly 100 duels and 37 battles, reportedly killing more than 200 people — and marooning one unfortunate opponent on a tiny island in the middle of a lake.

Enter the No-Sword Dragon

With some exceptions, Japanese swordsmanship and spiritual enlightenment were largely separate pursuits prior to the Edo period. The era’s two-and-a-half centuries of peace finally allowed samurai to reflect on the katana’s potential as more than just a lethal acupuncture tool. Before that, they were too preoccupied with survival to engage in philosophy. Bokuden, however, was a notable exception.

Bokuden, said to have never been wounded by the sword, eventually got so proficient at the katana, he started to question if the sword was even necessary for winning fights. His reflections culminated in the creation of the “No-Sword Style,” which emphasized the importance of avoiding unnecessary conflicts.

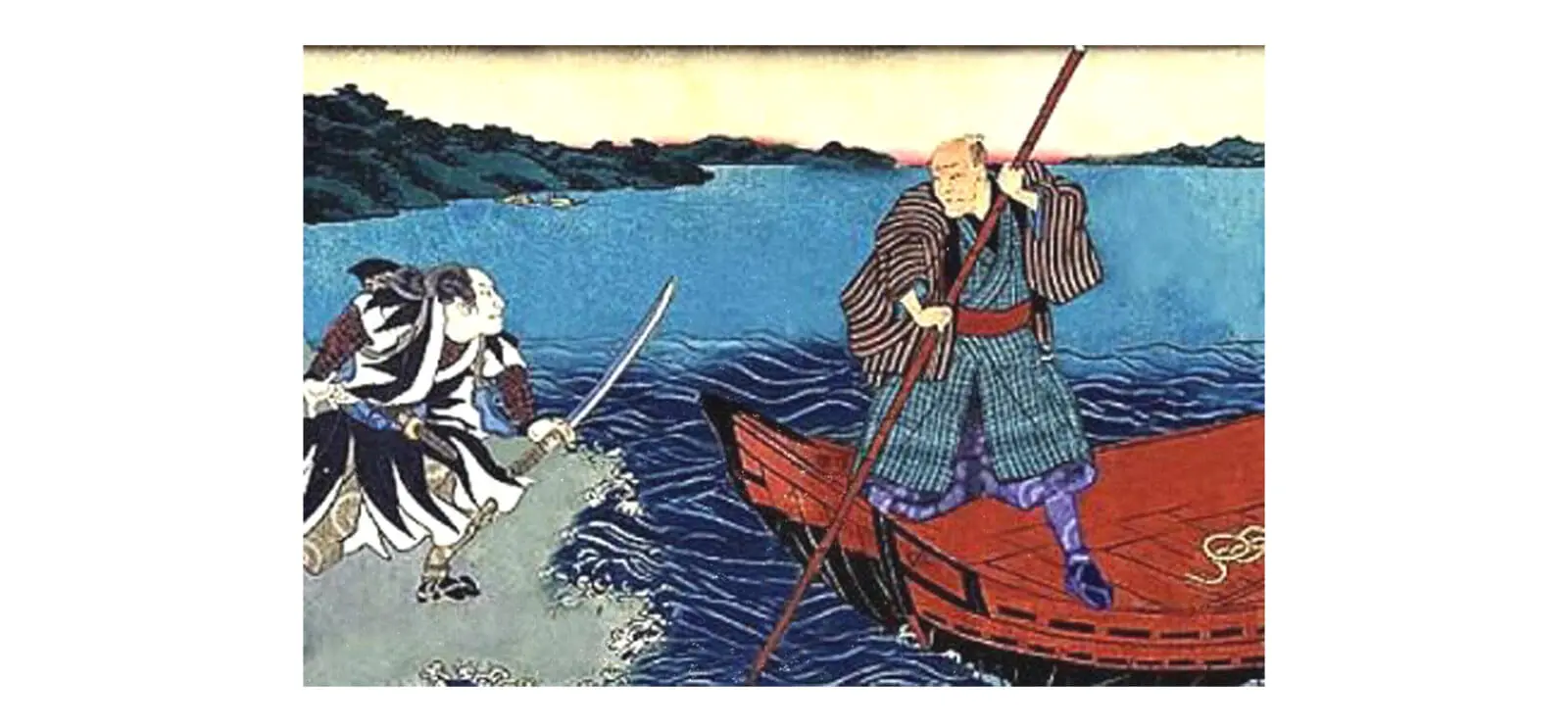

He got a chance to show it off when a young, loud warrior mocked the name of his combat system. Bokuden responded by challenging him to a duel on an island in the middle of Lake Biwa, the largest lake in Japan. Once they arrived by boat at their would-be battleground, Bokuden allowed his opponent to get off, after which he calmly rowed away, leaving his opponent stranded.

Centuries later, martial artist and actor Bruce Lee heard the story and loved it so much that he adapted it into the movie Enter the Dragon. In the movie, the hero tricks John Saxon’s boisterous character, Roper, into boarding a small boat, leaving him stranded away from the main vessel.

Wikimedia Commons

Tsukahara Bokuden: Never at Rest

Tricking opponents onto islands was not a sustainable battle strategy, so Bokuden never truly abandoned the sword. While his philosophy urged avoiding “unnecessary conflicts,” he made it clear that ambushes and self-defense fell firmly in the category of “necessary conflict.” If that happened, Bokuden later wrote, warriors had to keep calm and adapt their fighting style to the circumstances.

This adaptability helped Bokuden survive an attack by Ochiai Torazaemon, a warrior he defeated earlier in a public duel. Humiliated, Ochiai ambushed Bokuden in a forest near Kyoto. Expecting Bokuden to draw his katana, Ochiai was caught off guard when the sword saint assessed the situation and instead countered with a wakizashi (short sword), which was not part of his publicly known style.

This emphasis on adaptability was kind of a revolutionary thought in the world of Japanese swordsmanship, which up until then primarily focused on set stances and standardized moves.

Bokuden shared many of his teachings in the Bokuden Hyakushu. The text included practical tips, such as how to pass a stranger on the road — never on the right as that would leave you open to surprise attacks — and the most effective weapons against a particular fighting style.

Bokuden believed a naginata glaive shorter than 60 centimeters (known as a konaginata) was no match for a 70-80-centimeter katana. He demonstrated this in a duel with glaive-user Kajiwara Nagato, reportedly cutting his opponent nearly in half. One unconfirmed legend says that Bokuden prepared for the duel by trash-talking the konaginata within earshot of Kajiwara to infuriate him and trick him into choosing an inferior weapon, adding “master of psychological warfare” to his already impressive resume.

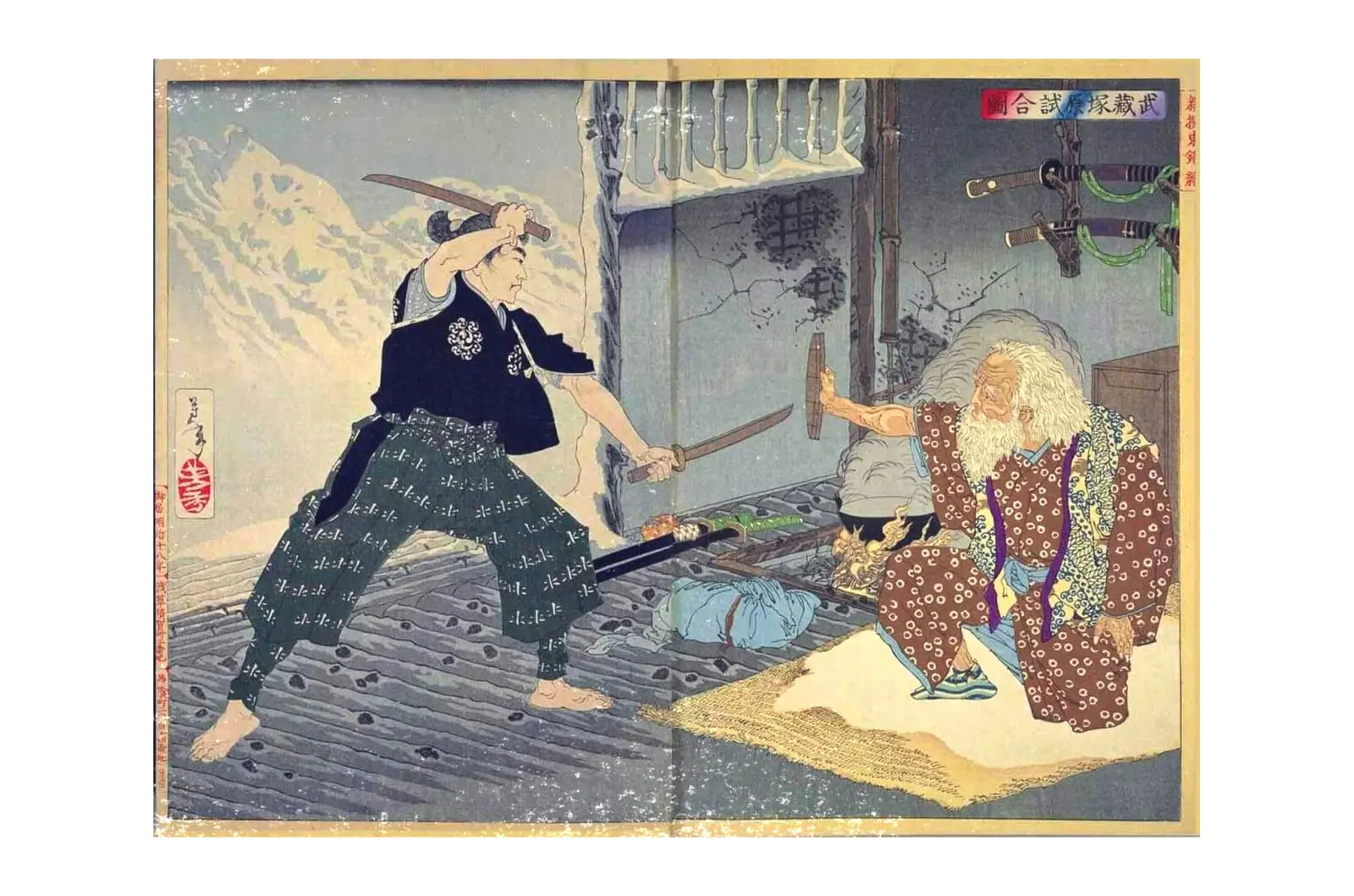

Tsukahara Bokuden Never Fought Miyamoto Musashi

Bokuden cleverly avoided this hypothetical “clash of titans” by dying 13 years before Musashi was even born. The reason why there are many portraits and woodblock prints depicting Bokuden defending himself against Miyamoto using a pot lid is more of a symbolic representation of the warrior’s philosophy of combat adaptability. They may also represent an early form of creative storytelling — essentially fan fiction — crafted by artists who lamented that history denied us a duel between the two sword saints.