We see the world in shapes and colors, but to draw it we need lines. By keeping the colors from spilling into one another and the shapes from becoming amorphous blobs, lines carry out an essential function, but remain mysteriously absent from our visual perception. An ability to first recognize and then replicate these invisible physical boundaries is what drawing is all about. If you can do it with some precision, and a bit of style, then something truly magical happens.

Western focus on painting over other art forms, has often meant that sketching, so long as it is done in scribbly and hasty strokes, carries an air of just-permissible artistic respectability not afforded to the deliberate use of an outline, long considered childish, eccentric or (worst of all) commercial. In Japan, this practice has enjoyed a higher reputation, especially in the world of ukiyo-e printmaking, where admirably precise and accomplished outlines are used to give definition to shapes and colors, forming images of stylish, but deceptive, simplicity and elegance.

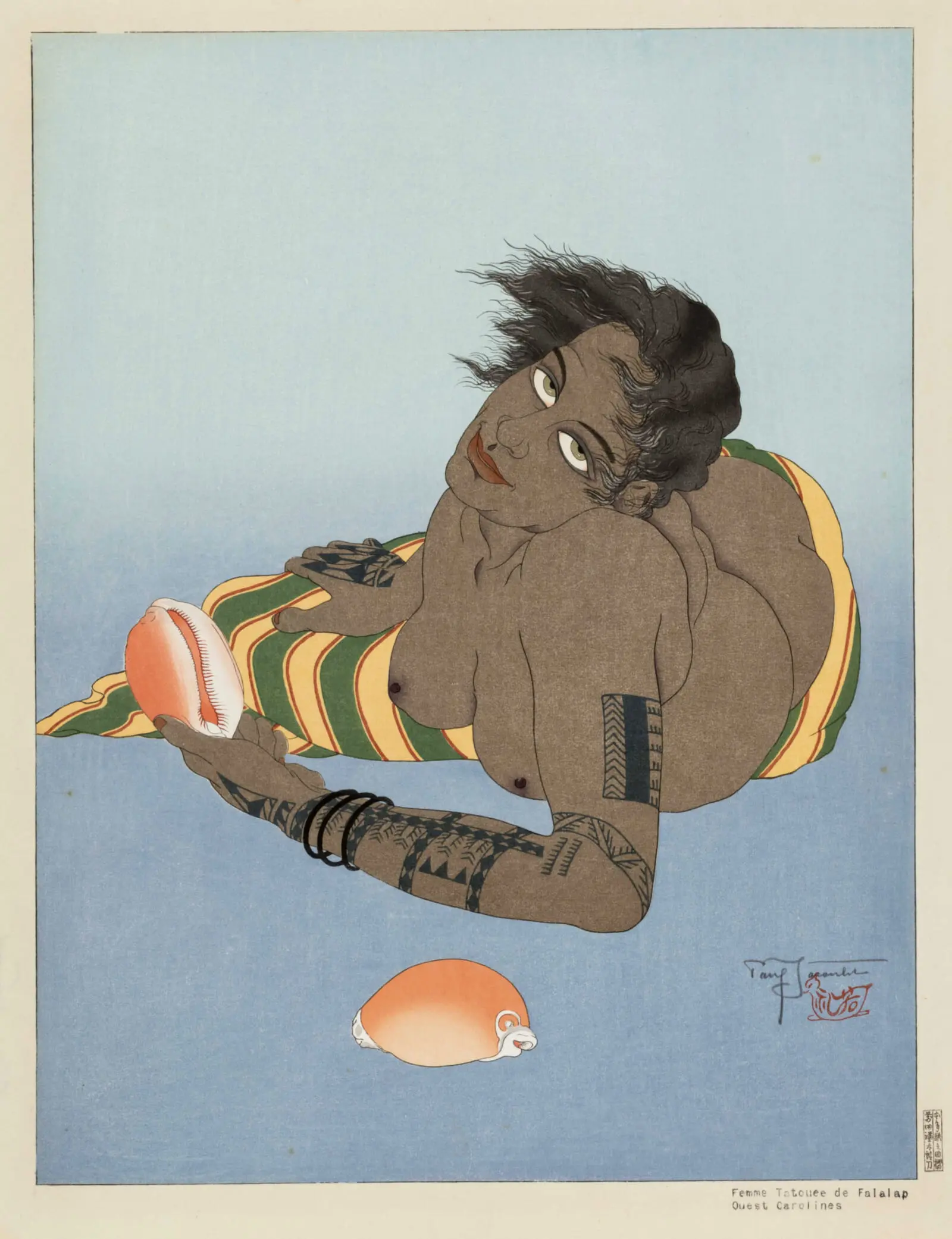

Paul Jacoulet “Tattooed Woman of Falalap, West Carolines” (Personal Collection) ©ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2023 E5060【2nd term】

Artistic Assimilation

French by birth, the artist Paul Jacoulet spent most of his life in Japan. His convivial approach to living and sincere dedication to art seem to have made him a popular and well respected figure in his adoptive country, and by becoming a non-Japanese master of 20th century ukiyo-e, he succeeded in an act of rarely-seen artistic assimilation. His prints, mainly portraits of the people of Japan and the Asia Pacific region, were often self-published in relatively small editions as he was something of a perfectionist, meaning that his output, prized by art lovers even in his lifetime, is now highly collectable and sought after.

Born in Paris in 1896, Jacoulet moved to Japan when his father, a university professor, was hired by the Japanese government to teach French to young Japanese aristocrats. He was raised in Tokyo, where he showed great academic and artistic promise from an early age. His flair for languages meant that by the time he was 16 he could speak French, Japanese and English fluently. English was taught to him by his neighbor Léonie Gilmour, the American writer and mother of the renowned sculptor, designer and landscape gardener Isamu Noguchi.

Jacoulet’s prodigious talents were no doubt given a helping hand by his father’s lofty status and material wealth. When he began his artistic studies in earnest, aged 11, it was under the illustrious tutelage of “the father of Western-style painting” Seiki Kuroda, and the great Japanese romanticist Takeji Fujishima, both legends of the Yoga (Western-style) movement of Japanese art. Jacoulet also became skilled in the art of bijin-ga (paintings of beautiful women) with guidance from the well-respected and in-demand artistic couple, Shoen and Terukata Ikeda.

Success built on such an auspicious grounding of good fortune and privilege in education could be easy to resent, but not in the case of Jacoulet, who wasted none of it. One look at the sinuous descriptive lines and vibrant humanity of his prints make it clear that he was born to draw, and would probably have lived as an artist even if he had started life scrawling on scraps of paper at a kitchen table. But like a sapling under glass, Jacoulet bloomed earlier and more colorfully than he might otherwise have done, thanks to the gilded encouragement he received.

Jacoulet became a full-time artist in 1921 after ill health brought a stint of work at the French Embassy in Tokyo to an abrupt close, with a 1929 trip to the South Seas proving particularly formative in his artistic development. The portraits he produced as a result of these eye-opening travels became a template that he was to follow, although never rigidly or unthinkingly, throughout his career. For much of the remainder of his life, Jacoulet’s work consisted of expressive but meticulous likenesses of Asian and Polynesian people in traditional dress, with more than a hint of romance and magic in the air around them.

Paul Jacoulet “The Black Lotus, China (Personal Collection) ”【2nd term】

Shin-Hanga

The artists of the shin-hanga (new prints) movement of the early 20th century sought to build on and modernize the traditions of ukiyo-e by the incorporation of western artistic elements, such as a more realistic approach to light and perspective. The works of Japanese masters like Hiroshi Yoshida and Hasui Kawase are still highly respected and in demand, but European artists then resident in Tokyo, Charles W. Bartlett and Friedrich Capelari also made impressionist-influenced prints with the encouragement of movement-instigator, the publisher Shozaburo Watanabe.

Although Jacoulet’s work fits into this category, it somehow marries Japanese and European practice in a more successfully modern and satisfying way than the work of Bartlett or Capelari, despite the imagination and beauty of both men’s prints. His use of flat planes, illuminated colors and the often-nonchalant poses of his subjects, have an art deco appeal that brings to mind the enchantingly chic pochoir plates used in French fashion magazines of the period. It is perhaps here, rather than in impressionism, that the western angle of Jacoulet’s art can be found.

Now, more than a century after his first prints were made, Jacoulet’s charming and eye-catching combination of modern representation and traditional processes means that his work is in no danger of losing relevance. His exquisite eye for colors, shapes and (especially) lines is clear from a glance. Also apparent in his prints, however, is an obvious affection for the people, fashion and nature of the world he inhabited; a joie de vivre that proves infectious to viewers regardless of time passed. In images that bloom with beauty, humanity and gentle good humor, Jacoulet infused his subjects with cheerful sensuality and a spark of life that time cannot erode.

The Paul Jacoulet exhibition runs until July 26 at the Ota Memorial Museum of Art.