by Denny Sargent

photos by Rebecca Sargent

Traditions have always died hard in Japan, and festivals often carry on ideas, symbols and practices that are sometimes venerated out of a sense of cultural continuity, not because they are especially relevant today. One tradition that is still very important and universal is our love for our children and wishing them long and prosperous lives. This is the root of “3-5-7 Day.”

“Shichi-Go-San” (reversed by westerners in translation to “3-5-7 Day”) is a festival held every Nov. 15. Its origins are lost in antiquity, but the basic theme is clear: survival. It’s a day that marked (and to a lesser extent still marks) several very important moments in a child’s life, the idea being that if a child survived past the third year, he or she would make it into adulthood.

Medical care has advanced tremendously over the last few decades, so infant mortality is now very low (especially in Japan), but it wasn’t so long ago that many infants and toddlers did not make it that far.

When they did survive the rigors, diseases and perils of their first three years, they were presented to the Kami (God/Spirit) of the local shrine in their finest ceremonial clothes to thank the deity for life and to receive continual good luck and divine blessings.

The process was again repeated, on the same festival day, when girls reached the age of 7 and boys reached the age of 5. At this point, they were said to be completely past the most dangerous and potentially fatal years of their young lives and it is then that they were, in the past, fully accepted as permanent members of the community.

It seems that long ago, due to mortality, infants were not even given permanent names until they were 3 years old. Thus this ritual probably marked the point when the child was actually given his or her “real” name. This is also the origin of the Christian “christening” ceremony in the west, the ritual naming of a child in recognition that he or she would survive, usually held a year or two after birth.

Nowadays, this may all seem a bit archaic and, to a certain extent, it is, but parents are not much different than they were hundreds of years ago, and every mother or father worries about their child’s health and prosperity. Thus the festival continues much the same.

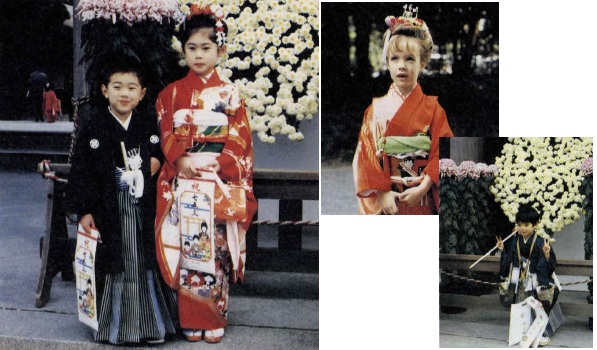

On Nov. 15, you will see no lack of beautiful children flocking to shrines with their proud parents in tow. Girls traditionally wear fantastic kimono and boys wear hakama (traditionally skirts), but lately many parents have been dressing their perfectly groomed children in western dresses and suits.

In days gone by, Shichi-Go-San was the first time for 3-year-old girls to have their hair put up. It was also the time when 5-year-old boys were dressed-up in their first hakama and girls of 7 received their first obi (kimono sash). Some traditionally minded families still do these things the prescribed way, but probably not as many as yesteryear.

Children who are brought to shrines quite often receive long colorful bags of special milk candy called Chitose-ame and, sometimes, balloons as well. Chitose means “1,000 years old” and symbolizes the wish all parents have that their children live a long time. Often a crane will be seen flying on the package, this being a reference to “1,000 years” due to a play on the Japanese characters for the bird and the time period.

Other foods associated with this holiday are tai or sea bream, a colorful and delicious fish, and oseki-han, red beans on white rice; two colors that symbolize good fortune as well as boys (white) and girls (red).

Shichi-Go-San Omamori (magic charms that contain the blessing of the shrine deity) and other Omamori are purchased for the children, maybe for protection from accidents or to help with studying. These can often be seen dangling from their bookbags during the rest of the year.

There is always, of course, a plethora of camera equipment, video recorders and so on at all the major shrines. The atmosphere is much like the western Easter Sunday, with everyone in their best clothes all set to show off their kids to the world. Sometimes entire extended families are gathered for the occasion and many people bring picnic lunches, eat a special (and expensive) meal at the shrine reception hall or make a full-day outing of it.

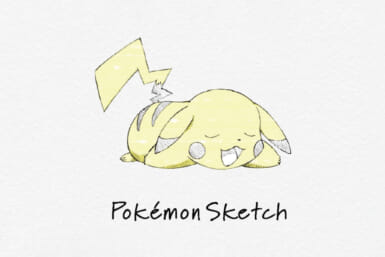

If you wish to bring your child to a shrine on this day, feel free! More and more foreigners are showing up at shrines on Nov. 15 with their freshly scrubbed progeny to enjoy the festive spirit and maybe even catch a little good luck. Keep in mind that Japanese count the “year” of pregnancy as the child’s first year of life, so by western reckoning, the children who show up are actually “2-4-6” and not “3-5-7.”

Even if you aren’t a parent, you shouldn’t miss the colorful fun of the “3-5-7 Day.” The places to see the full pageant in Tokyo are Meiji Shrine (Harajuku), Hie Shrine (Akasaka) Hiwaka Shrine (Akasaka) or Kanda Myojin Shrine (Kanda), but there will be plenty of activity at any neighborhood shrine.