D.H. Lawrence once called despair “the last refuge of the ego.” His dictum came to mind when I was introduced to the works of Tetsuya Ishida, a surrealist painter who captured the collective feeling of anomie that plagued Japan’s Lost Generation.

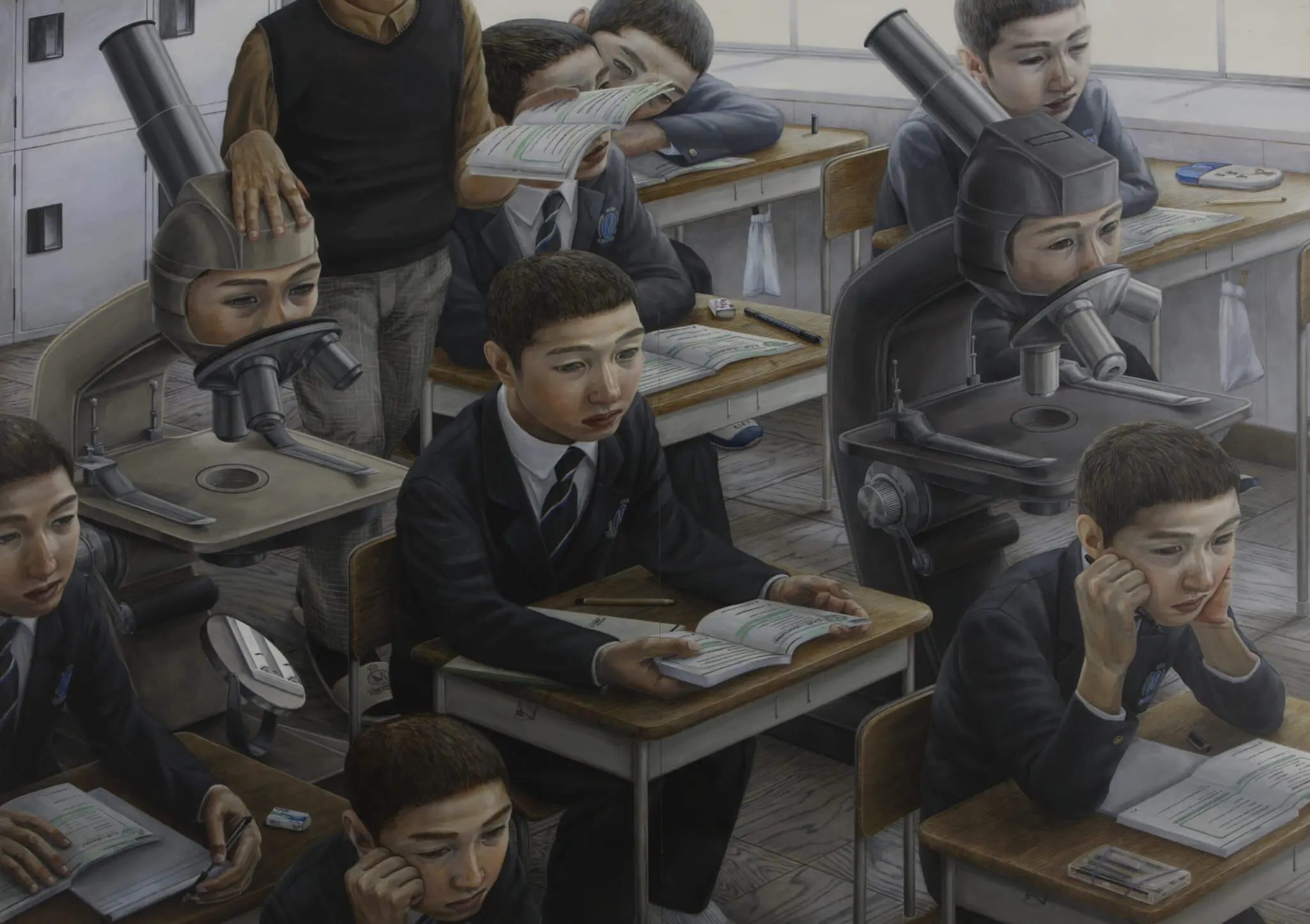

Though little has been written about Ishida’s personal life, he was born in Yaizu, a fishing town in Shizuoka Prefecture, in 1973. He later studied at Musashino Art University in Tokyo, where he developed a distinctive style, characterized by the dystopian fusion of human subjects and inanimate objects. He painted with acrylics and oils on canvas, rendering his tortured visions in dull and moody tones; grey-faced salarymen wracked with anguish and human-machine hybrids sapped of all vitality.

Despite a prodigious output of more than 200 paintings, Ishida had a short-lived career. Barely a decade after he first exhibited his artworks, he died when he was struck by a passing train — as news reports put it — just shy of his 32nd birthday. The subtext here, if it isn’t clear, is that he likely threw himself in front of it. Despair has its limits.

“People no longer fly”

Immortalizing Japan After 1989

In life, Ishida was a keen cultural observer, portraying the effects of Japan’s post-economic-bubble collapse and offering incisive takes on the cruelty of the human condition. His body of work comprises a series of not-so-subtle metaphors. An office worker presented as a soldier sent to die in the trenches, umbrella clasped against his chest and pointing upwards like a standard-issue rifle. An industrial reimagining of a sushi restaurant, where identical chefs use identical pumps to “refuel” identical men in identical suits. A man with the body of a plane, whose dreams of flight are quashed as he remains anchored to the ground. A distressed youth defecating in the middle of a half-eaten bento box bedroom.

His paintings are often called “Kafkaesque,” but this doesn’t explain what caused the nightmarish reality that inspired his work. Japan’s bubble economy of the 1980s was a too-big-to-fail pipe dream that was, in reality, too good to be true. Booming asset prices and financial deregulation flooded the markets with money. The production-line efficiency of Japan Inc. was seen as a blueprint for developed economies that feared they’d be left in the dust. It was a time of materialism and decadence, of funky Japanese city pop and the eccentric Toru Muranishi, of Nintendo’s rise to power and the Sony Walkman’s invention.

And then it popped.

Ishida was a student when the plug was pulled on Japan’s party. One of the coming-of-age disaffected who had their ambitions crushed, their opportunities eroded, their stresses compounded. As an artist, Ishida was already a pariah in conformist Japan — even attending art school was an act of defiance. But now cast further adrift because of the heady actions of the postwar boomers, he was consumed by a sense of betrayal.

“Seedling awakening”

Targeting Japan’s Salarymen Culture

Ishida took direct aim at corporate Japan with his art. It’s no coincidence his subjects are often buttoned up in bland suits as they are subsumed by the instruments built to serve society. There is also an industrial quality to his work, portraying an emotionless world of uniformity, while frequent digressions into childhood suggest he believed education was the true origin of Japan’s social malaise.

In a 1999 piece called “Shujin” (or “Prisoner”), a giant boy is imprisoned by his school, his head hanging awkwardly from the end of the building as though waiting for the guillotine to fall. The humor is dark but the intention clear: “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down.”

The factors that drive individualism in such a society are always curious. It needs to be founded upon the belief that one’s output is of true moral value; that conformity is tantamount to poisoning the soul. Ishida, whose work never climbed to the lofty heights of homegrown artists like Yayoi Kusama or Taro Okamoto, reckoned he would have found greater appreciation in the West, where carving one’s own path forward was lauded and seen as a prerequisite for critical success. It was from Europe and the US that he drew much of his inspiration, from the paintings of Ben Shahn and Vincent van Gogh to the psychological masterpieces of Fyodor Dostoevsky.

“Having a meal just like refueling”

Gone But Not Forgotten

Posthumously, Ishida has garnered a lot of attention abroad, including a retrospective exhibition in Madrid in 2019 that drew hundreds of thousands of viewers and was later displayed in Chicago’s Wrightwood 695 art gallery. It’s a sign that his work was prescient: the symbiosis of man and machine — and how that affects our interpretation of the self —has only become more ingrained in popular culture since his death.

He also had an admirable degree of self-awareness.

“When I think about what to paint, I close my eyes and imagine myself from birth to death,” he wrote in his journal in 1996. “But what then appears is human beings, the pain and anguish of society, its anxiety and loneliness, things that go far beyond me.”

How far beyond him do these things go? Ishida’s work isn’t just history painting, representing a narrow slice of Japan’s post-industrial development. It’s a timeless evocation of the struggles of being human, of growing up in a world where the few profit off the back-breaking work of the many; where, as Orwell might have phrased it, “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.”

Ishida’s paintings may be devastating, offering little in the way of hope. But they also serve as a reminder to hold power and authority accountable. Because every utopian ideal has the propensity to become a dystopian nightmare.