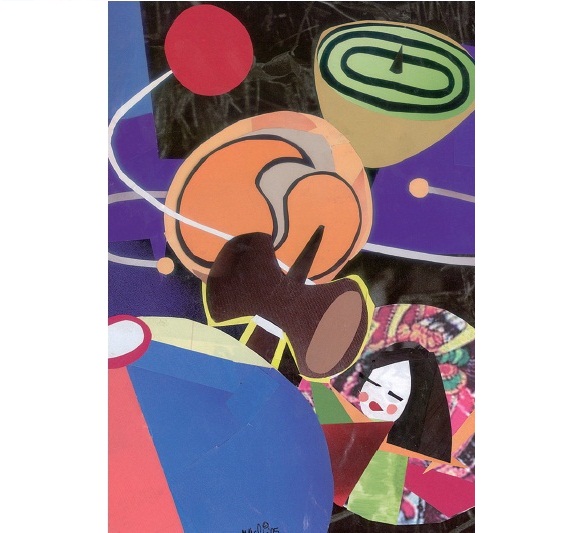

Kit Nagamura runs the rule over traditional Japanese toys

YOU’LL FIND them at antique markets, in souvenir shops, neighborhood toy stores and that wonderland of retail shops, Asakusabashi: traditional Japanese toys. But what are those waxy paper balloons called, and what’s the deal with that toy which looks like a martini jigger with a ball on the end? Though electronic games have cut into the market, simple toys for kids, like the infamous Slinky and Hula-Hoop, just keep springing back into play. Not only do such basic toys make excellent cultural gifts for friends back home, they can also reacquaint you with a side of your child (and yourself) that doesn’t need batteries.

Perhaps the best known of such Japanese playthings is the kendama, immediately recognizable with its bright red ball tethered by string to a wooden pedestal. Though the origins are obscure, a similar game gained popularity in 16th century France, when it was known as bilboquet, or “ball-and-pin.” Versions of the toy exist around the world, usually involving the challenge of trying to get a swinging ball into a cup, up on a spike, or through a hole.

Kendama is believed to have arrived in Nagasaki via the Silk Road, where in the 1700s it was a popular drinking game for adults (not for nothing did I compare it to a martini jigger). Losers would have to drink extra rounds, of course, and probably knocked themselves out with the wooden ball. By the Showa period in Japan (1926-1989), the game had caught on with educators (who noted players showed improvements in hand-eye coordination) and kids (who noted they were often better at the game than adults).

The Japan Kendama Association founded by children’s author Fujiwara Issei in 1975, set up standardized rules still used today in national competitions. Unless you’re hoping to compete, though, all you need to know is that the aim is to get the ball in any of the three cups or impale it on the stick. The cupped end of the stick is called the chuzara (or medium cup), the cups on the crosspiece are called ozara (big cup) and kozara (little cup), and the stick on the end is the kensaki (stick point). Getting the ball on the stick is the most challenging maneuver. But you guessed that, right?

A less painful game can be played with the wax-covered paper balloons called kami-fusen. Simply inflate by blowing in the little hole; no tie or hole covering is necessary. While not pneumatically airtight, they survive a lot of batting around without the “pop!” threat of their rubber counterparts, and they were designed to be squished flat and folded away for future play. Tokyu

Hands and various stores in Asakusabashi carry the balloons (packed flat) in traditional striped ball motifs, sea creatures (the octopus is hilarious), globes and fruits.

Too quiet for your offspring? Try bashing around with daruma-otoshi, a game which comes with (you have been warned) a hammer. To set this one up, you thread the hammer shaft down the center of a stack of wooden rings to align them, then pull the hammer out carefully, and set the daruma’s head on top. The object of the game is use the hammer to whack out individual parts of Daruma’s body without him losing his head. The Daruma figure is modeled after the Buddhist priest Bodhidharma, who meditated for over nine years, and consequently lost the use of his limbs. You get to speed up the process. Sound easy? It’s not. Quick wrist action, good aim and complete disregard for noise are necessary.

Another game that requires precision movement but is much quieter, menko, has seen a recent resurgence in popularity. The game usually features round cardboard disks brightly decorated with celebrities such as sumo wrestlers, manga characters, actors, athletes, etc. Player A puts a card she is willing to risk face-up on the ground. Opponent B has to throw down one of his own cards forcefully enough for the air pressure to flip A’s card over. If the card flips, B takes both cards. If not, B’s card is sacrificed to A. The first menko cards date from the early 1700s, and some Meiji era examples — affordable collectors’ items — can still be found at flea markets around town.

There are several versions of what Japanese call karuta; a word derived from the Portuguese for card: carta. Two varieties, uta-karuta (poem cards) and iroha karuta (alphabet, or proverb, cards) involve memorization in addition to Japanese language skills to play, but the hanafuda (flower cards) are not only lovely to look at, but simple enough for little children to understand. There are 48 cards, 12 suits (one for each month of the year), and four cards per suit with linking design elements that intrigue.

Finally, you may have seen plastic net bags of small colored glass beads, like marbles after a meltdown. The game ohajiki, favored by girls, starts when all the pieces are spilled on a slick playing surface. One player draws an imaginary line between two pieces. If she flicks one piece and hits her indicated target, she picks up both pieces. If she misses, she forfeits her turn, and the next player takes a shot. Play continues until all pieces are gone, and the winner is the one with the most bits. A game set can be picked up at many ¥100 shops around town.

Once the weather warms up a bit, look for another installment on traditional toys for outdoor play.