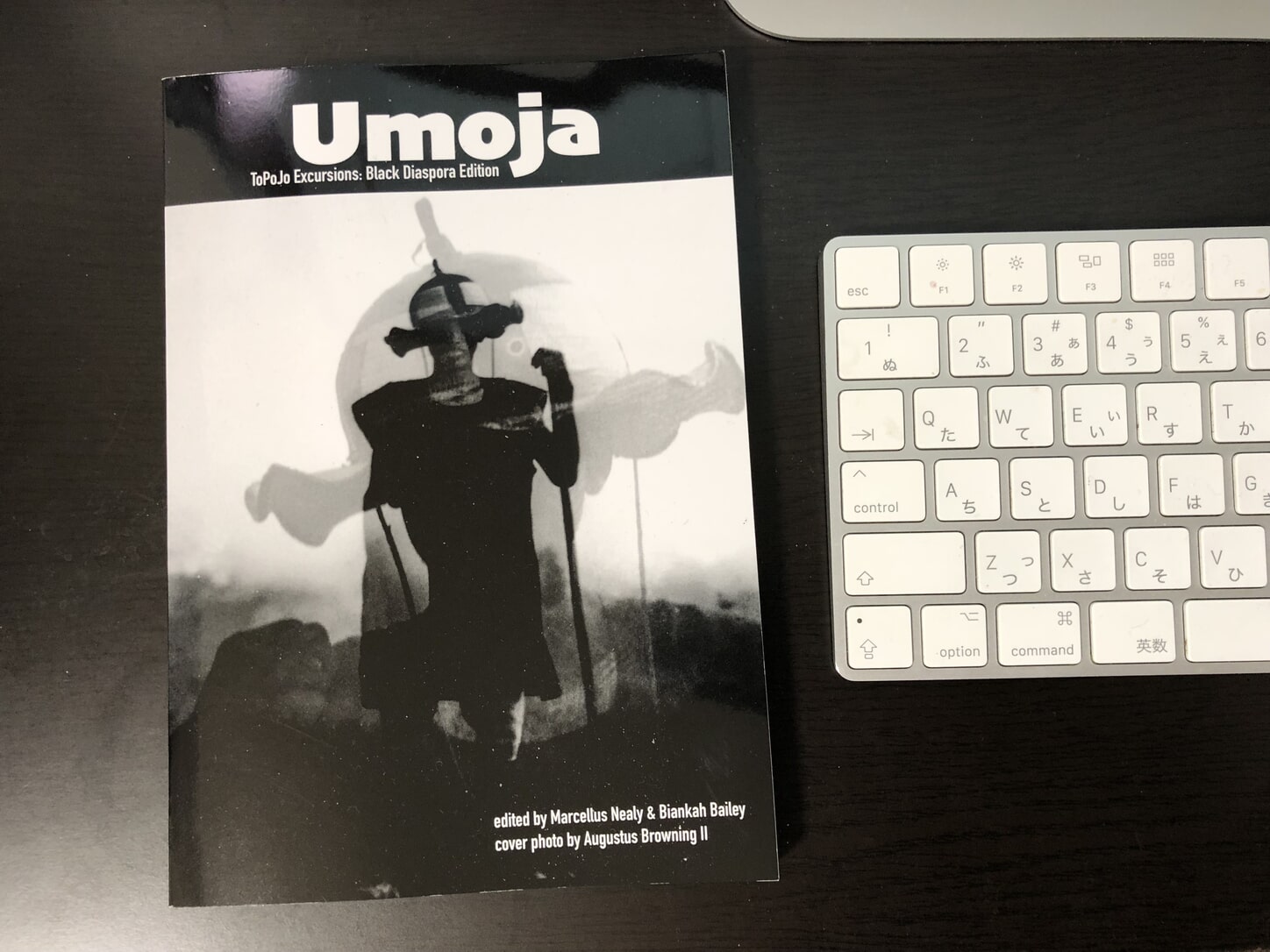

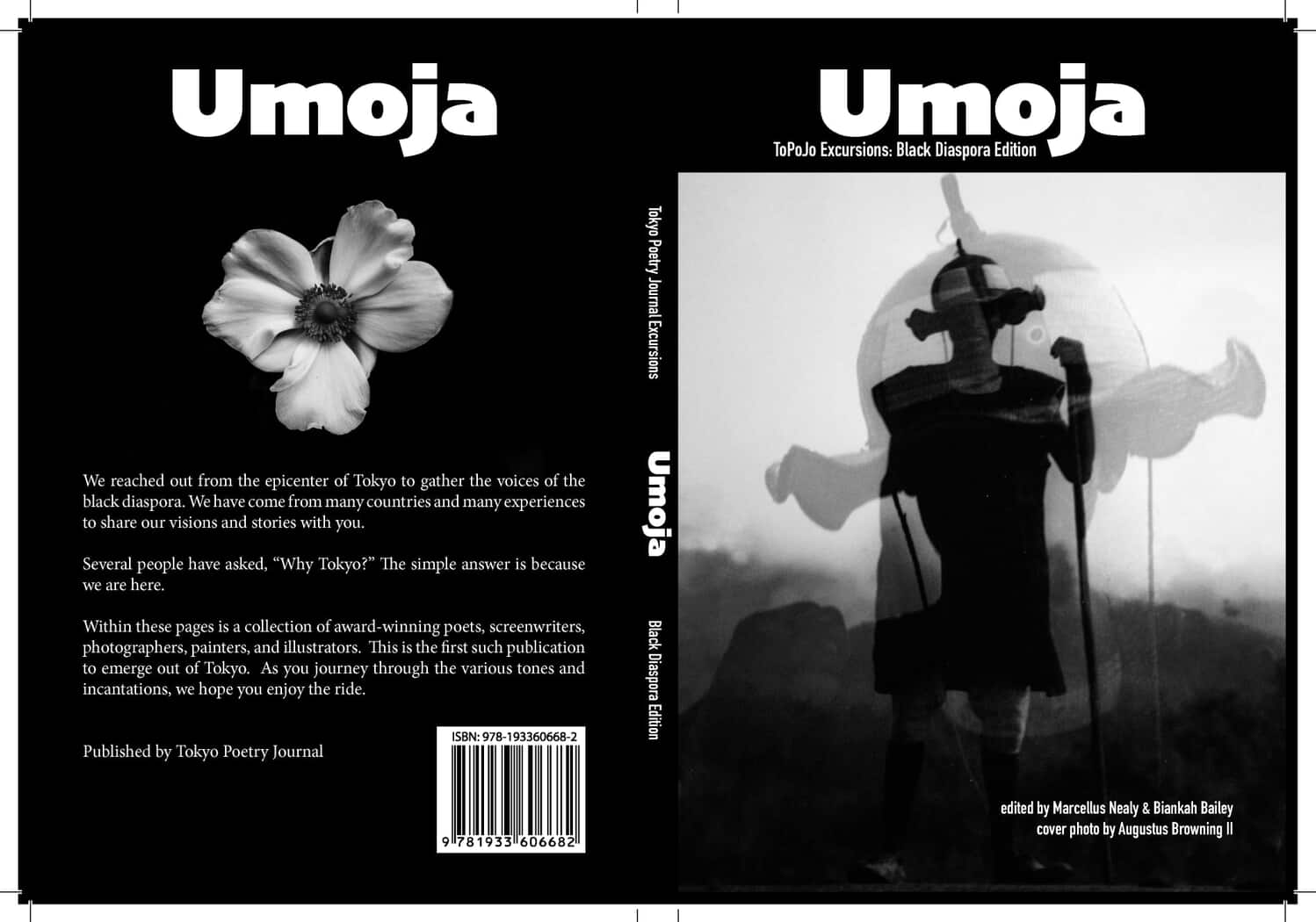

Umoja, (stylized as UMOJA), is Tokyo Poetry Journal‘s latest publication and Japan’s first anthology in English of art, poetry and prose by artists of the Black diaspora. Meaning “unity” in Swahili, Umoja is a testament to the chorus of voices that make up the Black diaspora around the world. Unlike other anthologies of Black artists, Umoja focuses mainly on writers and artists based in Japan, such as the anthology’s two editors, long-term residents Marcellus Nealy and Biankah Bailey.

“We tried to find a wide range of voices because we wanted Umoja to feel like the diaspora itself. Black people are multitudinous. There is no one way to be Black,” says Nealy, who has called Japan home for twenty years. The university professor has also worked as an NHK World Announcer and touring poet-in-residence with Japanese pop band Dreams Come True.

Marcellus Nealy

Why here, why now?

In light of the Black Lives Matter movement and anti-police brutality protests that erupted globally in 2020, Tokyo Poetry Journal’s editors sought out Nealy for the anthology. He then brought on Bailey to edit the book. It addresses the dearth of writers from the Back diaspora being published from Japan’s international community.

“The importance of this book is the same as it has, unfortunately, always been, which is to increase our opportunity for representation in the cultural landscape,” Nealy says. “The second reason why an anthology like this is important is because we live here in Japan, we create here in Japan. I’ve been in Japan since 1992, contributing to the culture. Publishing Umoja is one way we can make this place that we’ve called home, feel more like home.”

Umoja book cover

The genres, languages and backgrounds of contributors published in Umoja are as varied as the African diaspora itself. The journal includes poetry, prose, screenplays, artwork and photography. The contributors include actresses, models, musicians and filmmakers hailing from five continents.

On the diversity of the anthology, Bailey, a science fiction writer and administrator for the Black Women in Japan networking group, says: “Those different themes and topics, really represent us in the diaspora, individually, but also as a whole. Things like racism, gender discrimination, imagining the future and so on, these are, of course, very individual, but in some ways also very general. So, while they are separate, they still come together and that’s how we ended up with the concept for Umoja.”

Biankah Bailey (Photo by Alex Cooper Webster)

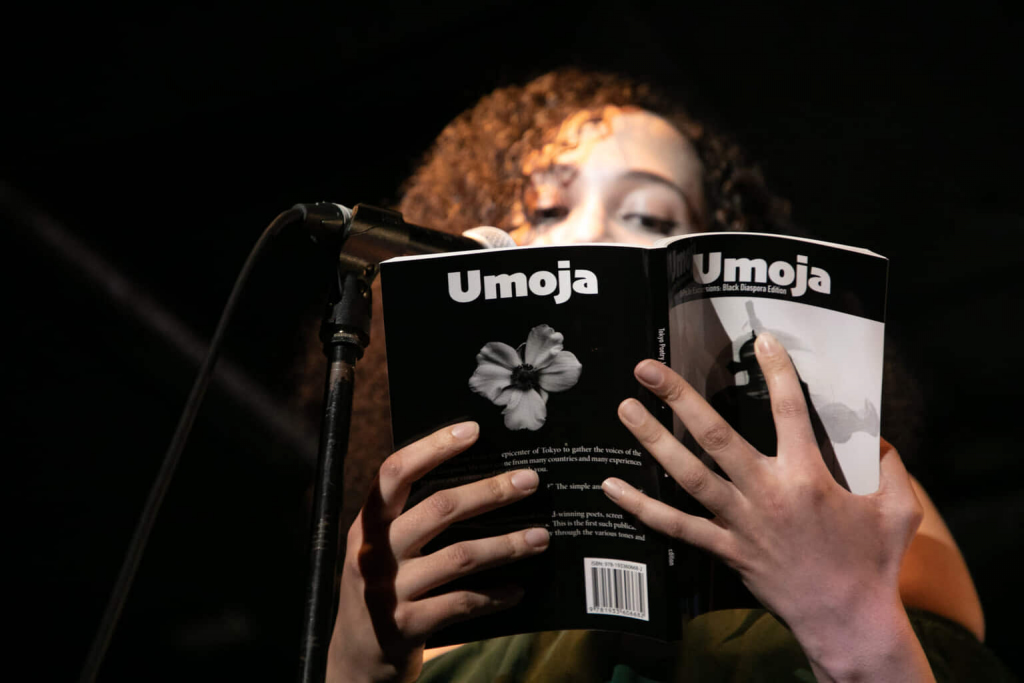

The Book Launch

On February 12, Umoja debuted with a launch event at Haretara Sore ni Mame Maite, a performance venue in Tokyo’s Daikanyama neighborhood. The night opened with smooth R&B covers of Jorja-Smith and TLC and original jams by American singer Afrodyty. Nealy, the dynamic MC who shared poems and spontaneous lyrical musings, led the audience from act to act. Poets shared their work, some joining online in the early hours of the morning from the UK and the US.

During interludes, Senegalese singer and percussionist Latyr Sy and Wagane Ndiaye Rose, as well as Ghanian percussionist Nii TeTe Boye, sang and beat drums at a rapid-fire pace throughout the night.

“We are all the same people living on this planet earth. We need to get together now, forever. People need peace,” Sy shouted before rhythmically slapping his drums.

Latyr Sy (Photo by Marcellus Nealy)

Poet and Tokyo-based South African model Frances Dyer shared a short but chilling poem about racial discrimination at a modeling audition in Tokyo. A pre-recorded video of British-Trinidadian poet and musician Anthony Joseph performing in London was streamed. Accompanied by a live jazz band of saxophones and bass guitars, he performed his spoken-word song “Maka Dimweh.”

In Swahili’s unifying spirit, Umoja brought together not only Black diaspora poets, but also other Tokyo international and Japanese poets.

“Although the book was about the Black diaspora, it wasn’t only Black people speaking,” Nealy says, referring to the book launch event. “It’s about whoever was there in the audience sharing this moment with us. The mic is open for you to talk, if you want to. Or to sing. If you brought a saxophone, pull it out and play. It’s a celebration. We’re celebrating culture, creativity and the arts.”

Chalice Leandra Davis (Photo by Marcellus Nealy)

Cross-cultural Collaborations

Poets from Japan’s national poetry slam league, Kotoba Slam (stylized as KOTOBA Slam) picked some poems from the anthology to interpret and give them a fresh twist.

The Kotoba Slam West Tokyo League’s host, Takaki Umino, interpreted Nigerian poet Adekeye Oluwasegun Lukman’s poem “Caged Voices” with a lyrical rap-like declaration of the power of one’s voice.

“Adekeye’s poem really struck my heart. I felt something from his poem: his human nature was suppressed by his surroundings. And I really sympathized,” says Umino.

Yuuri Miki, the co-founder of Kotoba Slam, performed an interpretation of Nealy’s poem “tokyo commuter train.” She believes Umoja and similar poetry events are also important for Japan.

“There were Japanese poets at the party who could not understand English at all. I believe that even if we don’t fully understand it, we can still feel the atmosphere and the rhythm of the poetry. It would be great if there were more places where people from all over the world living in Japan could present their different values through their works,” Miki says.

As a Jamaican who has lived in Japan for nearly 15 years, Bailey is excited about the impact Umoja can have on the literary scene in and out of Japan.

“Umoja is a first of its kind here. And it’s definitely an important part of the conversation of English language literature coming out of Tokyo. This volume has very decidedly Black voices. It’s really important for people to see what our experiences are living here as Black people in Japan,” Bailey says.

Umoja Highlights

Favorites from the anthology include the multilingual and sonically adventurous poems of author and former Tokyo resident, LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs. In the Japanese and English poem “Dejima,” she explores language and the Dutch colonial engagement with other cultures through the eyes of a Black-Indigenous female body.

“Do you like bananas?” and “Cilantro” by Mónica Lindo are brilliant prose stories in which food becomes a bridge for understanding disparate cultures as an Afro-Latina living in Gunma Prefecture.

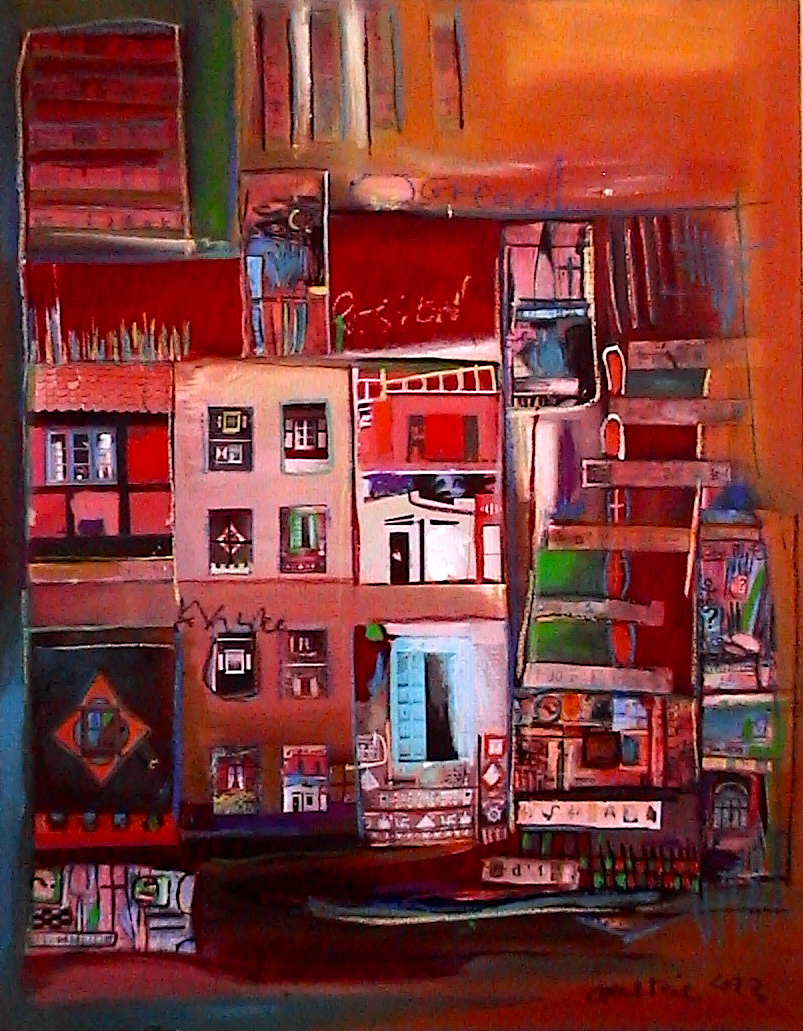

Painting by Amadou Tounkara, appearing in Umoja

Umoja features artworks too, including the nihonga-influenced paintings of Senegalese artist Amadou Tounkara and photos from renowned photographer and Kanagawa Prefecture resident, Augustus Browning II.

Browning II traveled across West Africa between 1982 and 1985 and, in fact, it is one of his photos that is featured on the cover of Umoja. “Fulani Man of West Africa (Nigeria northern area)” is a double-exposed image that in one shot captures a man who simultaneously appears rustic and futuristic. The photograph of the Fulani man, like many of the pieces, refuses identification and confinement, defies genre and reaches across borders and time.

As the first of its kind, the continuation of Umoja relies on readers purchasing and supporting the book. You can order Umoja: Tokyo Poetry Journal Excursions Black Diaspora Edition directly from Tokyo Poetry Journal, or at other major online booksellers.

Read more about Black creatives in Japan:

10 Questions With the Women Behind the Women of Color in Japan Documentary