Noh theater was created around the 14th century, though it’s based on traditions going back at least 1,000 years. It’s an ancient and complex art form that’s often hard to explain but that can be better understood by studying the language that it uses.

For example, an actor doesn’t “perform” noh. They “dance” it, pointing to the fundamental role of fluid, sliding movements in this minimalist yet majestic Japanese theater. Similarly, an actor does not “put on” a noh mask; they “attach” it, signifying a deeper connection than between man and mere prop. But what does that mean for, say, actors portraying demons? Let’s take a closer look at the power of noh masks.

Noh Masks as Living Objects

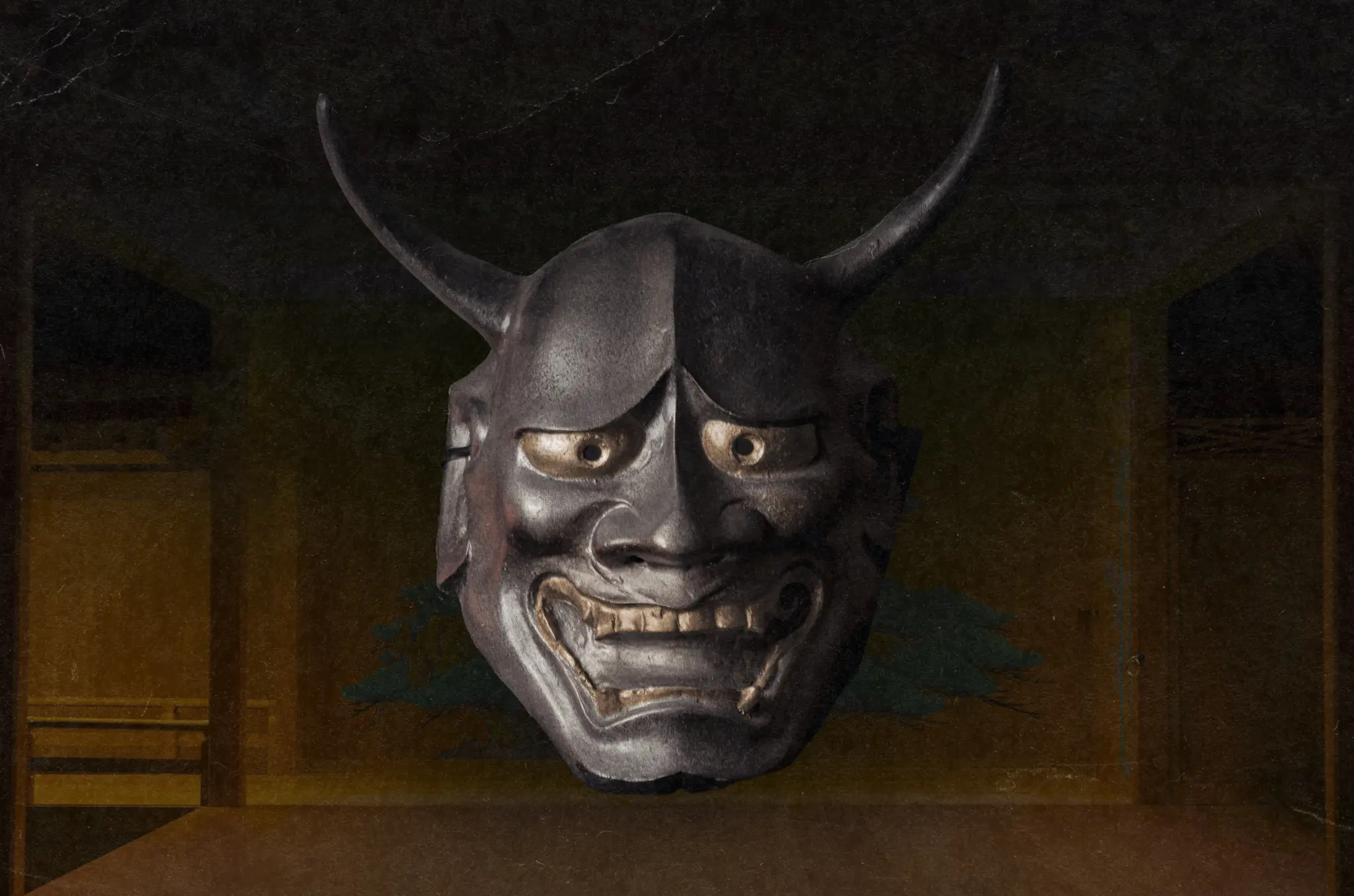

Originally, there were 60 types of noh masks, but today there are over 200, including — but very much not limited to — okina (old man) masks, onna (woman) masks and onryo (ghost and spirit) masks. But even within the same category, no two masks are truly the same, as each one is handmade by a professional artisan or, in some cases, by the noh actors themselves. This reinforces the idea that noh masks aren’t props but more like the actor’s partner in the dance-theater. Though not a super helpful one since the masks’ small eyeholes severely limit vision, forcing dancers to rely on their memory of everyone’s place on stage.

Each actor is expected to choose their own mask and project their soul on the frozen expression in order to become one with their partner. This is why a noh mask does not cover the entire face but rather exposes the chin and parts of the jowls. It makes it clearer that a masked actor is actually something like a fusion of two beings. That’s partially why the word for “mask” in Japanese is usually kamen — except in noh, where they are known as omote, literally “face.” But whose face? Some woodworkers (as omote are typically made from blocks of cypress) consider noh masks to be the faces of humans, but historically, they were the faces of gods.

Kishin mask, Tokyo National Museum Collections | Wikimedia Commons

Gods and Devils

The first noh masks most likely had a religious significance and served similar functions to masks in kagura, where the performer is said to become a vessel for gods. With time, this belief was refined in noh, which now basically believes that impermanent, imperfect humanity isn’t capable of expressing true beauty without help. That’s where the masks come in. Even noh actors who don’t wear masks are supposed to make their faces “like a mask” and, through it, become more god-like.

But the thing about a “god” is that the word has a much broader meaning in Japanese and can also include beings that people in the West would more likely describe as monsters and demons. In fact, the kishin (demon) masks were one of the first omote developed for noh theater to help actors tap into powerful emotions like rage, sorrow and jealousy. That’s an … interesting coincidence since Zeami, considered the father of noh, was banished in 1434 to the secluded Sado Island for reasons that have been lost to history. We don’t even know the exact date of his death because all official records of his exile were either lost or possibly (for the sake of a good, scary yarn) destroyed. Japanese people used to turn into powerful gods of wrath for far less.

Painting of a noh performer in a Hannya mask, from Dojoji Temple (c. 1900-1927) | Wikimedia Commons

Hell Hath No Fury

The noh hannya masks depict vengeful and jealous female spirits. Usually making an appearance in tragic love stories that teach lessons about the dangers of unchecked emotions, hannya masks are some of the most striking omote in the dance-theater. With their menacing horns, facial contours twisted in unholy ways and sharp fangs, the masks are meant to frighten the audience but also make them empathize with the suffering female spirit’s torment.

There are, in fact, many types of hannya masks, but most have a kind of profound sadness to them, which might explain why their name possibly comes from the Sanskrit word for “wisdom”; it takes a lifetime of experiences to be able to capture all the conflicting emotions of a hannya character in a piece of wood. Another theory says that hannya masks, worn by actors portraying characters controlled by their emotions, are so named because they symbolize the exact opposite of “wisdom” (showing Buddhist influences on noh theater).

Since noh is about becoming one with the mask, you might think there’d be some apprehensions about portraying malevolent supernatural creatures, especially since Japanese myths talk about people becoming demons by wearing a mask that ended up fused to their face, like in the legends of Shuten-doji. But in noh tradition, it’s believed that hannya masks actually ward off evil energies, and it’s unfortunate that they haven’t really caught on as talismans yet. Omamori are cool and all, but life would be so much more interesting if it were socially acceptable to walk around with kick-ass demon masks on. For spiritual protection.