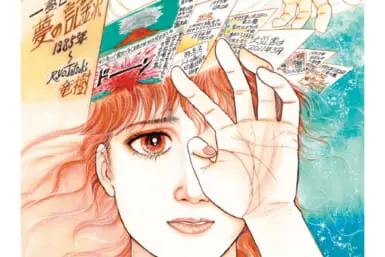

Released in 1997, the psychological thriller anime Perfect Blue is the only directorial work of Satoshi Kon for which he didn’t also write the story. But only technically speaking. The movie is based on the light novel Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis by Yoshikazu Takeuchi but very loosely.

The book and the movie start out similarly, but it doesn’t take long for the anime to diverge and follow Kon’s vision, which ultimately makes the story his own. Interestingly, while infusing the movie with elements that would go on to become part of his signature style, Kon also added one small detail to his Perfect Blue that today has made the film more terrifying than when it first came out.

Perfect Blue vs. Complete Metamorphosis

The film and the book tell the story of pop idol Mima Kirigoe as she tries to leave the world of singing behind and forge a more risqué persona for herself. This ultimately leads to some pretty gruesome murders. While both talk about the objectification and commodification of young women and men’s feelings of entitlement, the two go about it in totally different ways.

The book is essentially a slasher thriller with a narrative full of gory details to help us get into the mind of a deranged stalker who wants the object of his obsession to remain pure. In Complete Metamorphosis, the stalker is the source of all the danger and dread. In the movie, he’s more of a symptom of something larger.

Mima’s stalker (Me-Mania in the film, Darling Rose in the book) feels a twisted desire to protect her because, in his mind, she belongs to him. In the movie, he has competition, with added scenes of fans or people in the entertainment industry treating Mima as a product that exists to serve their needs.

The dehumanization she experiences is what contributes to the shattering of her perception of reality to the point where she can’t tell what’s real and what’s not anymore. This is wholly the invention of Kon, and it’s part of what keeps the movie popular nearly 30 years later. But it’s not what makes it so uniquely scary today.

Satoshi Kon’s Secret Ingredient: The Internet

The internet wasn’t commonplace when the Perfect Blue anime came out, but it had enough of a presence for Kon to incorporate it into the narrative via a website maintained by a Mima impostor who documents her day-to-day life in first-person and in terrifyingly accurate detail. Over time, this helps push the ex-idol to the brink of losing her sense of identity, wondering if this internet person is the real Mima. Fortunately, Kon takes it further.

The person behind the public yet anonymous internet journal uses it to essentially create their perfect Mima. The entries about her life are factually correct, like “I bought slightly more expensive milk today.” But when it comes to Mima’s thoughts about agreeing to a rape scene in a TV show or to pose for nude photos, the journal puts words in her mouth, blaming this or that person for “forcing” her to do it.

The real Mima was secretly reluctant to do all those things, but she mainly blamed herself. Yet through the medium of the internet, the villain was able to sculpt their own, online version of a real person to better fit the idea in their deranged mind.

Predicting Modern Social Media

Kon quickly saw how easy it would be to impersonate another person online and how perceived parasocial relationships with the object of one’s desire could disrupt an already unstable psyche.

It’s a bit of a spoiler, but it turns out that Me-Mania has actually been in personal communication with a person claiming to be the real Mima, and this sense of closeness and exclusivity gives him the fuel he needs to commit truly vile things.

At the height of Twitter, tons of celebrities became easily available to the ordinary internet user. They didn’t just share details of their private lives, but also directly communicated with fans.

The connection that Me-Mania has with Mima in the Perfect Blue anime is based on a lie, but the result is a sadly familiar one. There have been more than a few instances of celebrities exchanging inappropriate messages with both adults and minors who felt so privileged to get personal attention from someone they admired that they allowed things to go too far.

In the end, many ended up doing things they never knew they were capable of, and Perfect Blue perfectly taps into those fears all the way from 1997. It’s eerie.

Madness for Two

One interpretation of the Perfect Blue movie is that of a shared psychosis, with the real villain infecting Me-Mania with their own mental instability. It’s not clear if that was Kon’s intent, but there are enough elements in the film to support that theory and also give us all a weird feeling of déjà vu.

We’ve all seen examples of misinformation and conspiracy theories running rampant online, spreading like an infectious disease of the mind. It’s both amazing and terrifying if Kon was able to glimpse this clown-show future over 27 years ago.

As I sit writing this on October 12, 2024, which would’ve been Satoshi Kon’s 61st birthday, I wonder what the director thought about Perfect Blue later in life. He did live long enough to see the launch of Twitter and Facebook, but died before they became the brain-melting dumpster fires they are today.