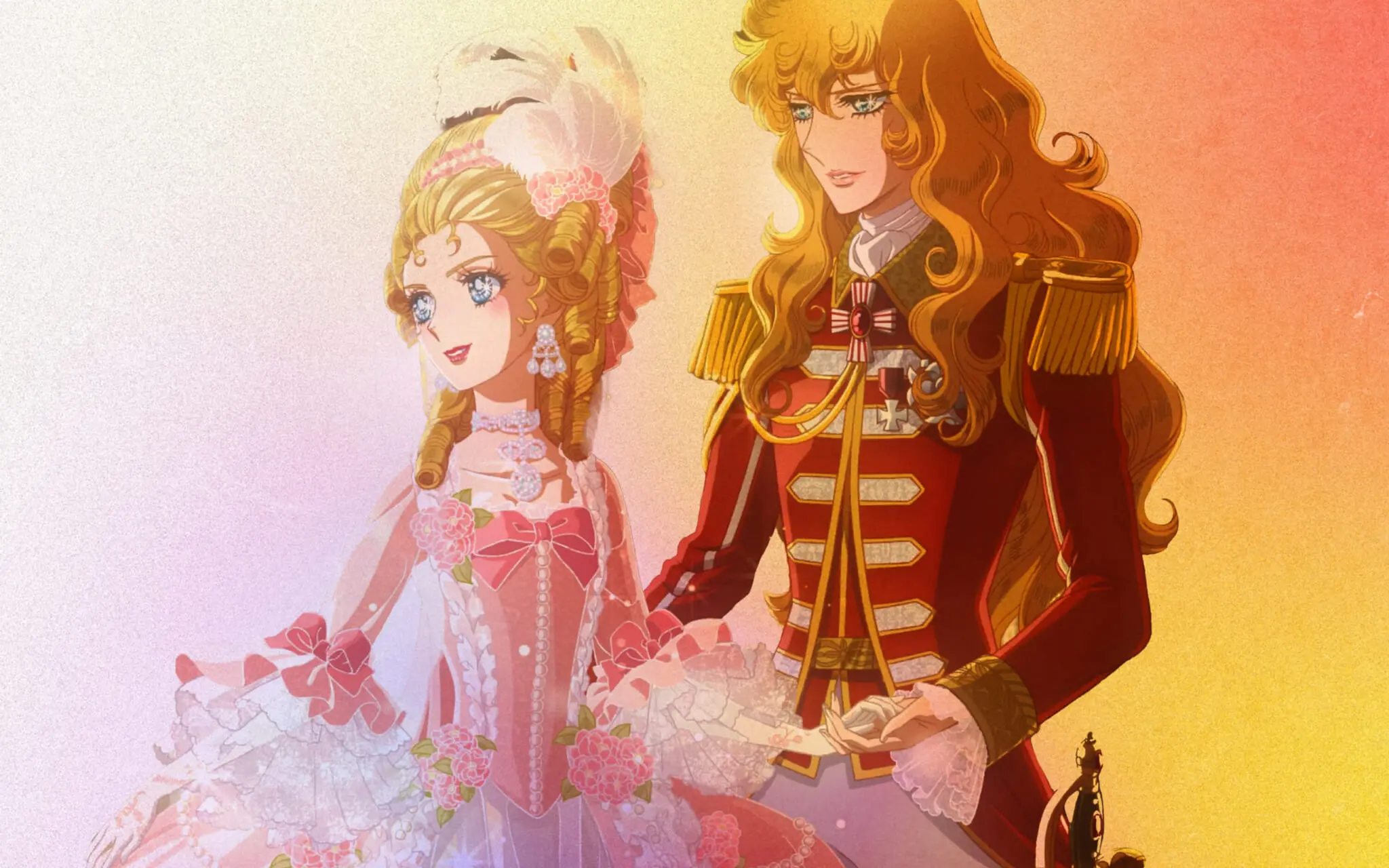

The Rose of Versailles manga by Riyoko Ikeda is a historical drama set before and during the French Revolution. It mainly focuses on Marie Antoinette and Oscar François de Jarjayes, a fictional commander of the Royal Guard and, more importantly, a woman raised as a man and treated as such by her subordinates. However, she never hides her true gender. The comic was originally serialized in the manga magazine Margaret from 1972 to 1973, and was instrumental in completely overhauling the image of shojo manga.

The Rose of Versailles proved that stories primarily targeting young women could be complex, audacious in their messaging, emotionally rich and have plenty of queer subtext. Perhaps that’s why the story was brought back into the public consciousness with a big-budget anime movie adaptation, which premiered in January.

Gender as a Performance

The movie condenses Oscar’s entire story arc from the comics into just 113 minutes, removing a few characters, not mentioning vampires and occasionally jumping forward in time. The result is a series of vignettes about Oscar’s life. She feels she’s a woman, and doesn’t express any desire to be a man. She also has plenty of male suitors who are attracted to her femininity. Yet by watching her seamlessly slip into the socially male role of a military commander, it’s hard not to notice an interesting thing about the nature of gender: it’s all just an act.

To be a man, for the purposes of her job, Oscar relies on her male name, the right clothing and an assertive attitude. It’s all things that are invisible, except for the clothes, but, lest we forget, high-heeled shoes, for example, were originally designed for men. It’s the same with names. Madison only became a popular female name after Daryl Hannah’s mermaid character used it in the 1984 movie Splash.

In the movie, gender is a role. All you need is to have the right costume and say the right lines in the right place. Since society agreed that only men can be commanders of the Royal Guard, whoever is doing the job must logically be a man and will be treated as such. Though this is challenged at one point, it gets resolved quickly. The underlying message that gender is a social construct is quite queer and perhaps something that a lot of people these days need to hear. It would have been better if the movie had said it more loudly, though.

Vive la Révolution

Ikeda used to be a member of the youth wing of the Japanese Communist Party, and her work is full of leftist themes such as female empowerment, class struggle and, of course, revolution. The movie ends right before the fall of the Bastille and is fully on the side of the French commoners. However, because the movie is so compressed, it also seems to say something more specific and slightly different about the nature of power than the source material.

It all starts with the audience being shown very little of the starving, struggling people of France. We get a few scenes of them on the streets, but the film tones it down when compared to the comic. The people are justifiably angry in the movie, but because we see so little of them, any deeper analysis of the reasons behind the revolution comes through the point of view of royals and nobles.

Because of this, the movie doesn’t outright say that we don’t need leaders and rulers. However, it does suggest that if we absolutely have to have them, they better be well-informed, good-hearted and actually address problems plaguing people. It’s a contract. A life free from struggle for a life of service.

The film rejects the idea of a God-appointed king, but it does seem to recognize the need for someone to be on top of things. This is hammered in on a few occasions, almost always involving Oscar, the golden example of what a true leader should be.

The final message is that if you have the privilege of holding other people’s lives in your hands, you had better not drop that privilege. The French nobility and royals dropped it without a second thought, so the people dropped a giant blade on their necks. This is, perhaps, something for modern oligarchs to think about.

Not the Perfect Messenger

Everything that The Rose of Versailles movie is advocating for is great but the way it does it could use some work. The film and the original manga have this unfortunate habit of romanticizing nobility, which might make sense since they are the main characters. But we probably could have used a few more examples of courage, sacrifice and honor from outside the nobility. They are there in the film, but they are few.

This adoration of nobility gets somewhat resolved near the end, but it still leaves Oscar a soldier and perhaps not the greatest spokesperson for the kind of messages the story seems to be going for. There might not have been a way around it without totally rewriting Ikeda’s work, but that just means the manga didn’t age well in all areas.

In the end, the movie isn’t perfect in its messaging, but what is? Still, if you find yourself agreeing with the movie’s intentions but not its execution, no one would blame you.