It’s 1874, the seventh year of the Meiji era. An unsteady camera wanders through the halls of a prison. Sheets of snow are falling outside, gusting in the winds of winter. A baby’s cries penetrate the moody silence. Her mother, pale, ravished, feverish, takes one, long look at her newborn child. We then hear the film’s opening words: “Yuki… You will live your life carrying out my vendetta… My poor child.”

And so we are introduced to the tragic case of Lady Snowblood, the demi-demon protagonist and titular character of one of Japan’s great postwar revenge films. Released on December 1, 1973, just as the snows were arriving in northern Japan, Lady Snowblood was a moving image tapestry of prophetic vengeance and hyper-stylized violence intermingled with the concept of karma.

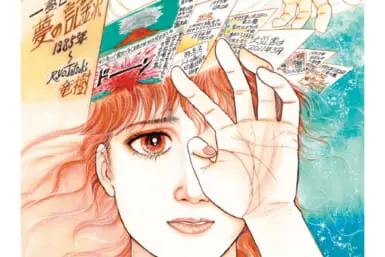

Lady Snowblood may have been influential in developing the female action hero archetype in Japanese cinema, but it was first introduced to the world as a manga series called Shurayuki-hime, a play on the Japanese name for Snow White. Written by Kazuo Koike, it ran in a serialized format from February 1972 to March 1973.

Koike set the story amid the social milieu of the late-19th century, when Japan’s renewed imperial ambitions were fostering civil unrest. He felt the story needed to hinge upon a strong female lead, a natural outsider from birth who wandered alone in pursuit of revenge. Koike envisioned a character “Beautiful outside, but a demon inside. A beautiful woman with a beautiful sword who turns cutting people down into an art.”

Violence as Poetry

To beautify gratuitous violence was always going to be a challenge for the movie adaptation’s director, Toshiya Fujita. It was a creative departure for the filmmaker too, whose nascent filmography was typified by coming-of-age dramas and a genre of cinema erotica called “pink films.” Other than having a prior working relationship with the Lady Snowblood actress, Meiko Kaji, Fujita’s desire to take on a graphic swordplay flick has never been fully understood. That said, nothing in the genome of the movie suggests Fujita, or the screenwriter Norio Osada, were venturing into unknown territory.

Lady Snowblood is told in chapters; a stylistic narrative ploy that helped define the composite parts of her quest. First, she is trained by a stern and unrelenting priest, who insists even the Buddha has forsaken her, before hunting the targets she was born to kill: the people who raped her mother and murdered her “father.”

The visual poetry of her blood-soaked frenzy is contrasted against the serenity of the provincial Japanese setting. Every strike of Lady Snowblood’s glinting katana severs a major artery, causing torrents of blood to gush forth from her victims. There is artistry in every graceful movement. She is formless yet balletic, directed by impulse and immune to mercy.

Kaji was the perfect casting for Lady Snowblood. She glows on screen. Her sharp, angular features, her arresting beauty and piercing death-stare, her white kimono with resplendent obi present a killer more angelic than demonic. Even her purple wagasa umbrella, a recurring motif throughout the film, operates as a symbolic omen of death.

All of this is underscored by the theme tune, “The Flower of Carnage,” a melancholic, spaghetti Western-infused composition with Japanese instruments, performed by Kaji herself. “In the dead of the morning, grieving snow falls. A stray dog’s howls and the footsteps of geta pierce the air,” she intones in the song’s opening verse. “I walk with the weight of the Milky Way on my shoulders. But an umbrella that holds onto the darkness is all there is.”

Lady Snowblood’s Hollywood Rebirth

Lady Snowblood proved successful enough to merit a sequel, the middling Lady Snowblood: Love Song of Vengeance. The original also helped popularize the exploitation films that were all the rage in Japan in the 1970s and it contributed to the demand for martial arts and samurai films worldwide. But its legacy has extended well beyond the boundaries of Japanese cinema. This is most notable in Quentin Tarantino’s 2003 homage: Kill Bill.

Tarantino’s filmography is full of offbeat, often-debased genre films that are littered with on-the-nose nods to his inspirations. And Lady Snowblood may have been as influential in shaping his artistic signature as grindhouse films, cowboy movies, blaxploitation flicks and the uber-violent cinema of Hollywood during his youth.

Lady Snowblood provided a direct blueprint for Kill Bill, particularly Volume 1, on top of which Tarantino essayed the story of Beatrix “The Bride” Kiddo’s revenge in his distinct cinematic language. Kill Bill is spliced into time-skipping chapters, as it tells the story of a trained killer hellbent on avenging the death of her daughter and husband-to-be.

Tarantino took the stylized presentation of the targets in Lady Snowblood and modernized it with a literal kill list, from which Kiddo strikes off the names. But rather than having a direct facsimile of Lady Snowblood, he channeled the character through two of his own: Kiddo is the reincarnation of her spirit, while the antagonist O-Ren Ishii is a visual manifestation.

The similarities don’t stop there. The two movies use manga style cut scenes to explore the back story and provide context. They both employ a mentoring priest who teaches their student the way of the warrior. Both play “Flower of Carnage” over their final, near-identical shots. And most importantly both explore what revenge does to the individual consumed by it.

You could argue that Kiddo’s revenge is more glorified. Perhaps it’s how she regains her sense of self, even. But Hattori Hanzo, the legendary swordsmith in Kill Bill, reminds us that one can be sympathetic to the cause, while remaining cautious about where it leads.

“Revenge is never a straight line. It’s a forest,” he tells Kiddo. “And like a forest it’s easy to lose your way… To get lost… To forget where you came in.”

Lady Snowblood, on the other hand, was destined to get lost in the forest. “Before we enter this world, we are marked by karma,” she says, making it clear that any victory is going to be a pyrrhic one. And with every target she pursues, she is shorn of the last remnants of her humanity. It is revenge as revenge ought to be. A dish best served cold.