This article appeared in Tokyo Weekender Vol. 1, 2025.

To read the entire issue, click here.

Every year, between 70,000 and 90,000 people are reported missing in Japan. While the majority, including teenage runaways and senior citizens with dementia, are eventually located, some manage to vanish without a trace after engineering their own disappearances. They are known as johatsu, from the Japanese word for “evaporation” — “evaporated people” who hope to never be found.

The term “johatsu” first came into use in the 1960s. It exploded into the public consciousness in 1967 following the release of Shohei Imamura’s pseudo-documentary film A Man Vanishes (Japanese title: Ningen Johatsu), which chronicled the abrupt disappearance of a Niigata salesperson. In the 1970s, the word was commonly used in the media to describe people looking to escape the hardships of daily life: workplace stress, for instance, or unhappy marriages.

After Japan’s economic bubble burst in the 1990s and increasing numbers of people fell into debt, the phenomenon became even more widespread. In 1994, Masanori Kashimura published a book titled The Complete Manual of Disappearance to provide advice on how to start a new life from scratch. Several companies also emerged around this time, offering to help people discreetly relocate.

There are many reasons why someone might decide to disappear: Some are escaping loan sharks, while others are fleeing abusive relationships, stalkers or oppressive employers; there are also people running away from the shame of failed businesses or ruined reputations. In their documentary Johatsu: Into Thin Air, which was released in November 2024, German filmmaker Andreas Hartmann and Japanese director Arata Mori delve into the turmoil that these evaporated people face — as well as the suffering of those they leave behind.

‘Night Movers’

The specialized businesses that help people vanish are known as yonigeya, which the film translates as “night movers.” Their customers are often desperate; for some, reaching out to a yonigeya feels like the only alternative to suicide.

One of the documentary’s main subjects is Saita, the founder of one of Japan’s best-known night movers, Yonigeya TSC. (She prefers to go by just her last name for safety reasons.) Saita, too, is a johatsu — on its website, the company bills itself as the “only private organization run by experienced domestic violence and stalking victims” in the country.

A typical transaction begins with a phone call to discuss the details of the case. There’s then a face-to-face meeting, usually at the client’s house (if it’s safe to do so), to provide a better understanding of the place the person hopes to escape. Once everything’s been agreed upon, preparations will begin to transfer the customer to a secret location.

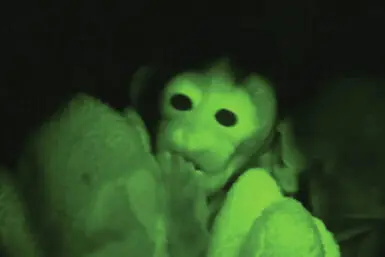

The final step of the process is where the film begins: In the opening scene, we see Saita and an employee in a car, waiting for a man in an abusive relationship to escape from his home. After a few minutes, the client, his face pixelated, hurriedly gets into the vehicle, and they quickly drive away. He’d managed to get out when his partner went to take a bath.

Discreet Disappearances

In the pre-production process, Mori and Hartmann contacted several night movers. They decided to focus on Yonigeya TSC for two reasons: They felt Saita was the most cooperative and that she had the most compelling story.

Beyond Saita, the film introduces viewers to several johatsu, including one of her staff members, Sugimoto. Shamed by the failure of his business, he told his son he was going away on a three-day work trip, but never returned, leaving his wife to take care of the children. Another of the documentary’s subjects, Kanda, was driven underground almost four decades ago due to debts he owed to the yakuza.

There’s also a couple, whose names aren’t given, living in a spare room in a love hotel in the middle of nowhere. They fled their home after being regularly threatened by their boss. The harassment was intense; according to the pair, any mistakes they made were punished with fines, which meant they were never sure how much they were going to be paid.

“Just listening to their story was traumatic,” says Mori. “You hear about so-called black companies in Japan, but usually it’s at a large firm, where people are overworked. I’d never heard anything like this before, where workers are forced to pay. It clearly messed with them psychologically, and even now, they can’t leave the love hotel, so it’s like they’re in a prison.”

Mori and Hartmann don’t merely focus on those who have vanished — the documentary also follows a devastated mother in search of her son. Since police in Japan are unable to initiate an investigation unless there’s proof of a crime or an accident, her only option is to hire a private detective. Japan’s strict privacy laws, however, make it an extremely difficult task. ATM transactions can’t be tracked, access to phone records is forbidden and security camera footage is not open to the public.

“It’s not just the people who are fleeing from their lives who are suffering,” says Hartmann. “We, therefore, felt it was important to show the opposite side of the johatsu world, from the perspective of a mother who’s been left behind and is desperately trying to find answers. She didn’t make the decision to leave, but she has to deal with it.”

Shedding Light on a Taboo Topic

Hartmann decided to start working on Johatsu after completing another documentary, A Free Man, about a Japanese individual who chooses to be homeless. Both deal with similar themes: the pressures of a rigorously performance-oriented society, and just how far some people will go to escape them.

Mori, who was born in Japan but has lived overseas for nearly two decades, felt drawn to the project as soon as he heard about it. Researching for the film proved to be an eye-opening experience for him. “Of course, I knew the term johatsu, but I didn’t realize how prevalent it was in Japanese society,” he says. “It’s generally seen as a taboo topic — but when I spoke about this project to close friends, many of them said they knew someone who had disappeared.”

Although the documentary has been well received at various festivals around the globe, the original version of the movie won’t be distributed in Japan. That was the promise the two directors made to the film’s protagonists. An alternative version, which was created using deepfake technology to hide the identity of the participants, made its Japan premiere at the 20th Osaka Asian Film Festival.

For more about the documentary, visit Mori’s website and Hartmann’s website.