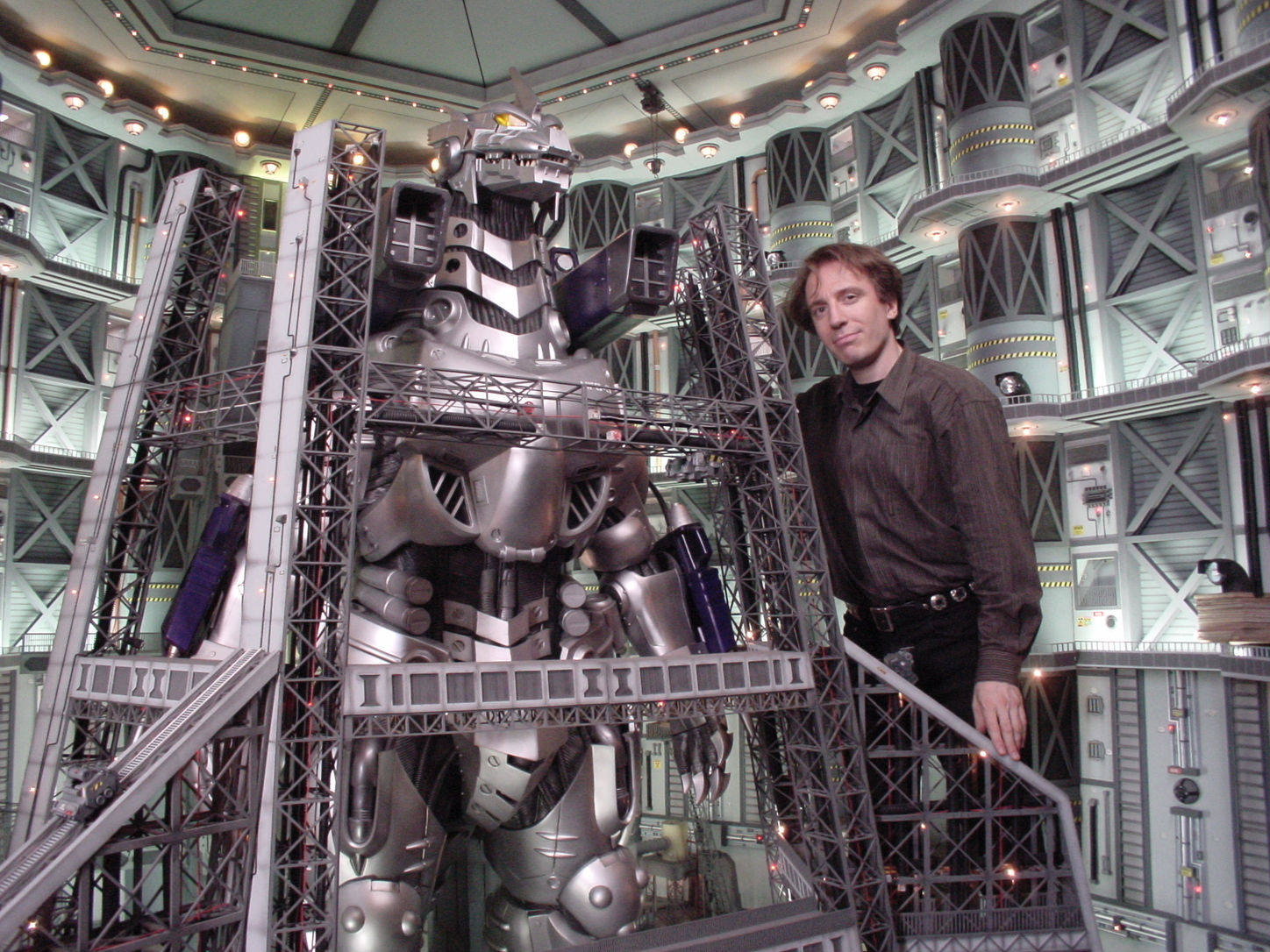

They say that you have to walk a mile in someone’s shoes to truly understand them. But New Yorker Norman England went beyond footwear, getting to wear Mizuho Yoshida’s full Godzilla suit on the set of Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001). This alone gave him more insight into Japan’s famous movie monster than most people will ever get. But that was just one moment during a fascinating course in the art of kaiju filmmaking that lasted from 1999 to 2004. During that time England worked at Toho Studios as a set photographer and correspondent for the horror film magazine Fangoria.

Lucky for us, he’s willing to share all that he learned on the sets of movies like Gamera 3 (1999) and Godzilla vs. Megaguirus (2000). On November 22, 2021, Awai Books published England’s memoir Behind the Kaiju Curtain: A Journey Onto Japan’s Biggest Film Sets that takes readers exactly where the title promises. Tokyo Weekender sat down with the author to learn more about his book.

What did you learn from becoming Godzilla?

I wore the Godzilla suit for around 10 minutes one afternoon at Toho. It was a dream come true, but I knew I could never do it day in and day out for months on end. And I certainly couldn’t do it without being grumpy half the time. To play Godzilla, which is the top job in this field, you go in knowing it’s not going to be a field day. The suit is so heavy. Strength, stamina and perseverance are necessary qualities for a suit actor.

It’s also essential to have a positive attitude. I’ve been on small sets where the person in a suit complains about this and that trifling matter. A person like that won’t go far in this business. At the same time, you know the staff has your back, that they would risk their lives to save yours if it came down to it. In this way, the suit actor gives their all without worry and without complaint.

The studio had no problem with you borrowing a vital prop like that? What was the atmosphere on kaiju movie sets back then?

There’s a lack of unions in Japan. In Hollywood, unions (in theory) strive to regulate work responsibilities and keep safety protocols in place. Nothing like that exists here. For example, although I was on Godzilla sets as a reporter and photographer, I’d be enlisted to move equipment around and help build props. Hours on Japanese sets are insane. As I describe in my book, the last day on the special effects set for a Godzilla film went on for over 30 hours with only a 30-minute break at around 4am.

On the flip side, there’s real team camaraderie on sets in Japan. I’ve never encountered the “that’s not my job” line you often hear in the US. So, when something is needed, like pulling out a stock of pre-fab miniature buildings for Godzilla to walk through, every available hand will jump into action, mine included. And when it came to me wearing the Godzilla suit, I just asked suitmaker Fuyuki Shinada and the Toho office. They both kindly gave me the okay.

It sounds like you became part of the kaiju film crew family. Was that difficult for a foreigner?

Any non-Japanese person living in Japan knows you can get away with certain things because many Japanese consider their culture impenetrable. By this I mean, those of us not raised here are often forgiven lapses in cultural protocol.

For example, I wasn’t expected to use honorifics when speaking to the cast and staff on the Godzilla set. This helped to create a friendly atmosphere around me. The benefit was that it opened up the filmmakers to me in a way different from domestic reporters. Also, many of the cast and staff wanted me, as a non-Japanese, to understand them and their work and take what they’d told me to the outside world.

And did it work? Did you understand what Godzilla means to Japan?

Nailing Godzilla down into a concise definition is difficult because Godzilla is like a chameleon (pun intended). His character has radically changed since first being introduced in 1954 and is constantly refit to meet the needs of the times. For example, in the 1954 original, Godzilla was a kind of “specter of war” and illustrated what military conflict does to those who don’t have a hand in the decision-making process that leads to war.

Soon after, Godzilla became a kind of reptilian action hero, fighting various threats like King Kong, King Ghidorah and Gigan. In 1971, when pollution was a growing concern, Godzilla vs. Hedorah (the Smog Monster) saw Godzilla pitted against a sludge-like creature. More recently, in a reversal of being an anti-war statement, the Godzilla in Shin Godzilla (2016) was used to suggest that Article 9 of the Japanese constitution hinders the government from taking swift military action when Japan is under attack.

Many people only want monster-on-monster brawls. But you think a human perspective is equally important, right?

Story and human characters are as important as special effects; the two have a symbiotic relationship of equal importance. I believe the best example of this (live-action and special effects working in perfect tandem) is Shusuke Kaneko’s Gamera trilogy from the 1990s. In fact, my book begins on the set of Gamera 3, the last film in this trilogy.

However, a portion of the audience does view kaiju films like elaborate wrestling matches. I found the recent Godzilla vs. Kong a bore because the human scenes felt like fillers, which, in my opinion, gave the monster scenes no sense of urgency. In contrast, Gamera 3 uses humans to electrify the kaiju scenes and make them more relevant to the audience. A good kaiju movie shows how a monster attack affects the lives of ordinary people.

Would it be fair to say that Behind the Kaiju Curtain is more than a “Godzilla book?”

Had I released it 20 years back I think it would have been a straight “This is how they make Godzilla movies” publication. While there’s nothing wrong with that, I felt anyone could write such a book simply by gathering and wading through the mountain of printed material in Japan covering Godzilla productions. So, as time passed and with the urging of friends who were aware of the depth of my experience, I began to see that I’d actually made a journey into an aspect of Japanese culture not many outsiders have experienced. It’s as much an adventure into Japanese culture and a bygone era as any you’re likely to find.

Norman England currently works as a filmmaker, columnist for the Eiga Hiho film magazine and a subtitler whose work includes the English translation of Takashi Miike’s The Great Yokai War: Guardians (2021). Buy his memoir, Behind the Kaiju Curtain, here.

All photos courtesy of Norman England.