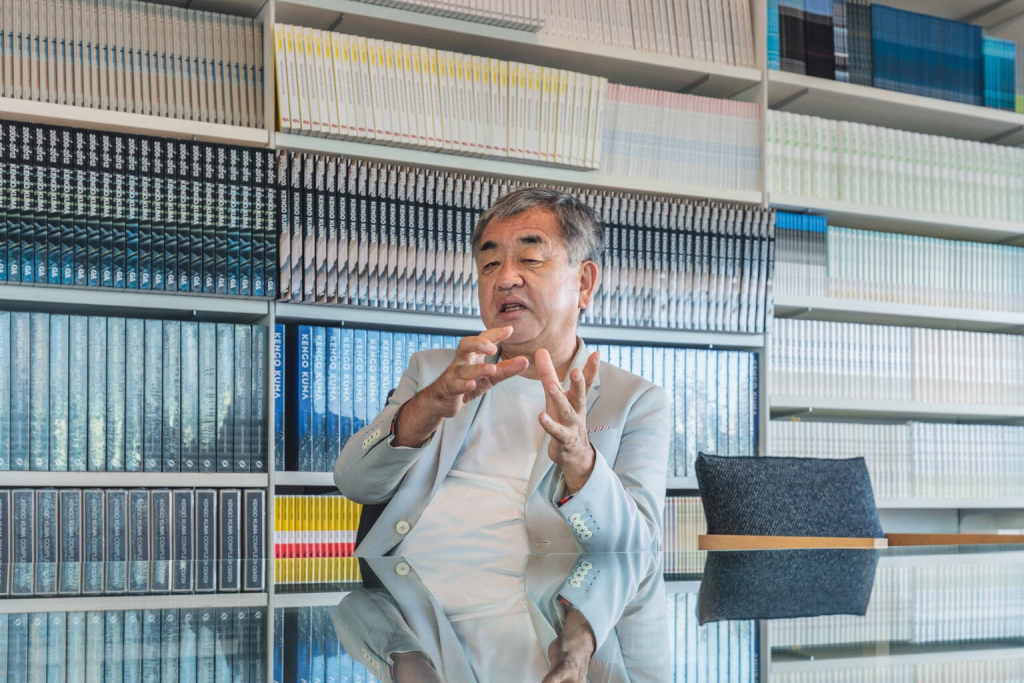

On the day we meet with Kengo Kuma, his Tokyo office is bathed in light and we can hear the muffled rustle from Baiso-in Temple’s bamboo trees below. This glass-walled meeting room on the rooftop is Kuma’s favorite place. “My private office is always a mess,” he says.

Natural light played an important role on the day Kuma decided to become an architect. It was when he first walked into Kenzo Tange’s National Gymnasium for the 1964 Olympics as an elementary school student. “The natural light coming from the top, reflecting in the pool – it looked like that was the day the planet was being born,” Kuma says.

Old is the New “New”

Kuma believes that in the future 80 percent of all architecture will be renovations of sorts. “Recycling is exciting and emotional for me,” says Kuma. “It means I can communicate with people who passed away, with the soul of the past.” He echoes the Shinto belief that objects have a soul. Some of the legendary architect’s most recent projects exemplify this philosophy of reuse and renewal.

The 2017 Harmonica Yokocho Mitaka is adorned with old bicycle wheels as façade. Keio Takaosanguchi Station was redesigned in 2013, instead of being demolished. Internationally, the Besançon Art Center in France was designed by Kengo Kuma & Associates (KKAA) to inhabit an old brick warehouse building.

This is in stark contrast with Tokyo’s penchant for demolishing its most noteworthy architectural landmarks – Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel and more recently the former Harajuku Station building are just examples. This year, Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower will also be taken from the city’s urban landscape. However, this comes with some consolation that some of the capsules will be preserved. Kurokawa was among Kuma’s early inspirations, and he subscribes to Kurokawa’s Metabolist view that “buildings should have life.”

It’s not the new generation that demands wrecking balls. Kuma believes young people are into vintage as an attempt to reconnect with lost heritage. He says the trend to renovate old buildings is getting stronger. Young couples are moving into countryside traditional houses. They are renovating abandoned houses and schools and turning them into cafés and galleries. These trends are also driven by economic hardships, and more recently catalyzed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dreams of Tokyo’s Future

The KKAA studio is within walking distance from the Japan National Stadium that Kuma and his team designed for Tokyo 2020. With the Olympic Games in full swing at the time of our interview, but also winding down, the conversation naturally wandered off to the stadium.

The National Stadium

What happens to venues after the Olympics has always been a hot topic. Kuma maintains that sports venues are incredibly versatile and can be used for decades after the Games. Case in point, the Kenzo Tange Gymnasium that wowed Kuma in 1964 is a host venue for some of the Tokyo 2020 events. “Olympic venues have a strong identity as buildings and can be used forever,” Kuma says. “Buildings that only have function, but not identity, are meaningless.”

The structure of Japan National Stadium was built with wood sourced from all of Japan’s 47 prefectures. Kuma’s dream is making Tokyo a wooden city again. Together with more greenery it will create a perfect harmony. He mentions one of his recurring inspirations, Horyuji Temple in Nara, built in the 7th century from wood. “If maintained properly, wood can last centuries,” Kuma says. He agrees that achieving wooden Tokyo will take time, but it’s not just a pipe dream. He has already started and expects to see his dream fulfilled in his lifetime.

Sunny Hills, Tokyo

When it comes to architecture ideals, Kuma doesn’t mince words. “Tokyo was destroyed by concrete.” He doesn’t have any praise for the boring glass boxes full of bland offices that have overtaken Tokyo. We concur they are a Bubble Era exuberance, and Kuma is determined to leave them even further behind.

Building Identity

Decades and scores of buildings designed later, this world-famous architect is even more rooted in nature. His architecture exhibits the humbleness that skyscrapers lack. Kuma’s buildings don’t rival mountains, they learn from them and blend with them. And in doing that, they are outstanding.

He often finds deeper meaning towards his work when building in Japan’s countryside. “In Tokyo I can only talk to the construction site manager. It’s all about budgets and schedules. But in the inaka [countryside], I can talk to every artisan,” Kuma says. His architecture aims to utilize local materials and people, giving back to the community.

Odunpazari Modern Museum in Eskisehir, Turkey

This also goes for his international projects, both for materials and design. Kuma says he doesn’t want to impose his design, and he believes in collaboration instead. He is especially proud of his international team of architects from all over the world working in the Tokyo branch. “Cultural exchange is the mother of creation,” he concludes.

Kengo Kuma photos by Anna Petek

This article was published in the Sep-Oct 2021 issue of Tokyo Weekender. To flip through the issue, click the image below.