Across a wooden bench, a stage is being assembled. Calligraphy brushes in miniature, a stainless steel pan and vivid food color dyes. From a large earthenware pot, Takahiro Yoshihara scoops out a viscous starch syrup and molds it into a dull white ball the size of an egg. Focused and fingers deft, he is about to sculpt a Japanese icon. The catch? He only has three minutes before his preferred medium hardens into permanence.

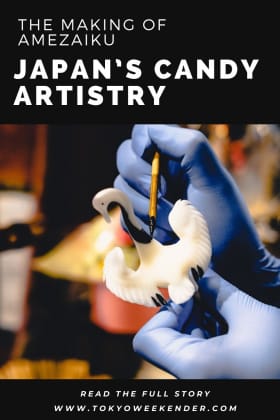

Amezaiku Yoshihara is his stage. The red noren curtain outside the flagship branch in Sendagi depicts the simple tools used in amezaiku: a wooden stick for mounting and a pair of hand scissors used for delicately snipping and shaping the taffy. Made from a corn syrup starch called mizuame, the ball of taffy is over 80 degrees Celsius when a candy artist comes into contact with it. To make the minute shapes, artists often wear nothing more than a pair of thin rubber gloves for protection from the heat. Fluidly drawing, snipping and shaping, the artist can call forth a zoo of candy animals.

Yoshihara’s story begins over 15 years ago and further still, tracing back to the carefree days of childhood. “In the olden days, traveling performers would go to parks and shrines and make candy figures as part of their show,” he says. Amezaiku masters would travel around, plying their sweet intricate wares on audiences young and old. They were performers and confectioners molded into one.

Some of the oldest literary depictions of amezaiku date back to 1746. An old bunraku puppet show called Sugawara and the Secrets of Calligraphy recounts the corralling song of a traveling candyman: “Hey, hey, kids, come around and get a candy bird, it’s a candy bird!” Pairing their kamishibai, bunraku and other street performances with a candy souvenir, these dynamic salesmen flitted from park to park. In the Edo period, the technique was akin to glass blowing with sculptors breathing life into their creations. “As regulations on hygiene got stricter, the art fell out of favor with the public and it became harder to find people who could do it,” says Yoshihara.

While these candy souvenirs evolved and faded from the scene a little, the whimsical nature of these Edo-period performers linger in the present-day amezaiku maker. Moving into the shop and watching Yoshihara work, it is clear how candy sculpting has become a riveting show on its own. Starch syrup ball mounted, Yoshihara teases out two white arches using a pair of Japanese scissors. He doesn’t hesitate to crimp a pair of glossy wings, each snip shaping individual feathers from within the taffy egg. All the while, he prods at the memories of his younger self. “My master was a man of few words,” he recalls of his time as an apprentice at the age of 27. “If he wanted to teach you something, he would ask you to imitate it and then practice and practice until you got it right.” He remembers the process of trying and failing, chuckling fondly at those days. “A rabbit is the easiest to make. The foundations for making all other animal forms out of amezaiku start from it as well. It was the first one that my master taught me how to make.”

The challenge of crafting dragons under the same time constraints makes Yoshihara prickle. “The candy hardens at the same rate regardless of the shape you’re making,” he says. “There is a lot of detail that needs to be done with scissors and there are a lot of difficult techniques.” He is relieved that he can make them inside the controlled environment of a store. “While I still enjoy making amezaiku outside, there are so many variations to control such as humidity, outside temperature and the consistency of the taffy.” The shapeless ball of taffy now carries wings poised and is ready for flight. Yoshihara draws out the neck with an elegant swoop before dabbing on black food coloring. Another dip into his miniature paint pots and the unmistakable red crest emerges. In three minutes, Yoshihara has birthed an intricate and symbolic red-crested crane – fit for modern Tokyo.

These days, Yoshihara manages two storefronts in the Sendagi area. At one they run guided workshops for visitors who wish to come and learn how to make amezaiku for themselves. For around ¥3,000, weekend visitors can try their hand at making their choice of a rabbit, dolphin or bird. Foreigners are welcome, as one visitor from Australia said: “The workshop was made to be super accessible for us. They provided a video that translated the steps into English so we could follow along. It’s a truly unique food experience for foreigners looking to try something different.” Since opening the store in 2008, Yoshihara has taken the art as far afield as New York and has even raised the profile of amezaiku at diplomatic events that promote Japanese culture abroad. But while Yoshihara may have been the first to turn the traveling confection into a storefront, his intentions are far from breaking tradition. “I still love making amezaiku at festivals. During the summer, I still participate in small festivals in and around Nezu,” he says. “The delight on children’s faces when they get to see this kind of performance at festivals makes me really happy.”

His pioneering storefront was intended to give amezaiku a more permanent home where people could see the tradition at its most vibrant. “Having a place where people can come back to see amezaiku being made gives it a sense of continuity,” says Yoshihara. “Through their communication with me, they can pick and choose a one-of-a-kind creation. And a child’s amezaiku story can become a tale passed on to another generation.” From his earthenware pot, Yoshihara readies another batch of taffy. This time it’s for a couple. From the menu, they choose a pair of rabbits – their shared zodiac sign. They want to celebrate their upcoming wedding. The sound of their smartphone cameras acts as the soundtrack to the performance, with beaming selfies at the end.

A girl reliving her exchange year abroad; a couple celebrating an engagement. It’s no longer just a sweet souvenir complementing a neighborhood show. Through possibly thousands of performances, Yoshihara has reached into Tokyo’s past to sculpt a uniquely modern connection to an Edo-era performance.

For more information on Amezaiku Yoshihara, see their official website here.

All images by Iain Salvador