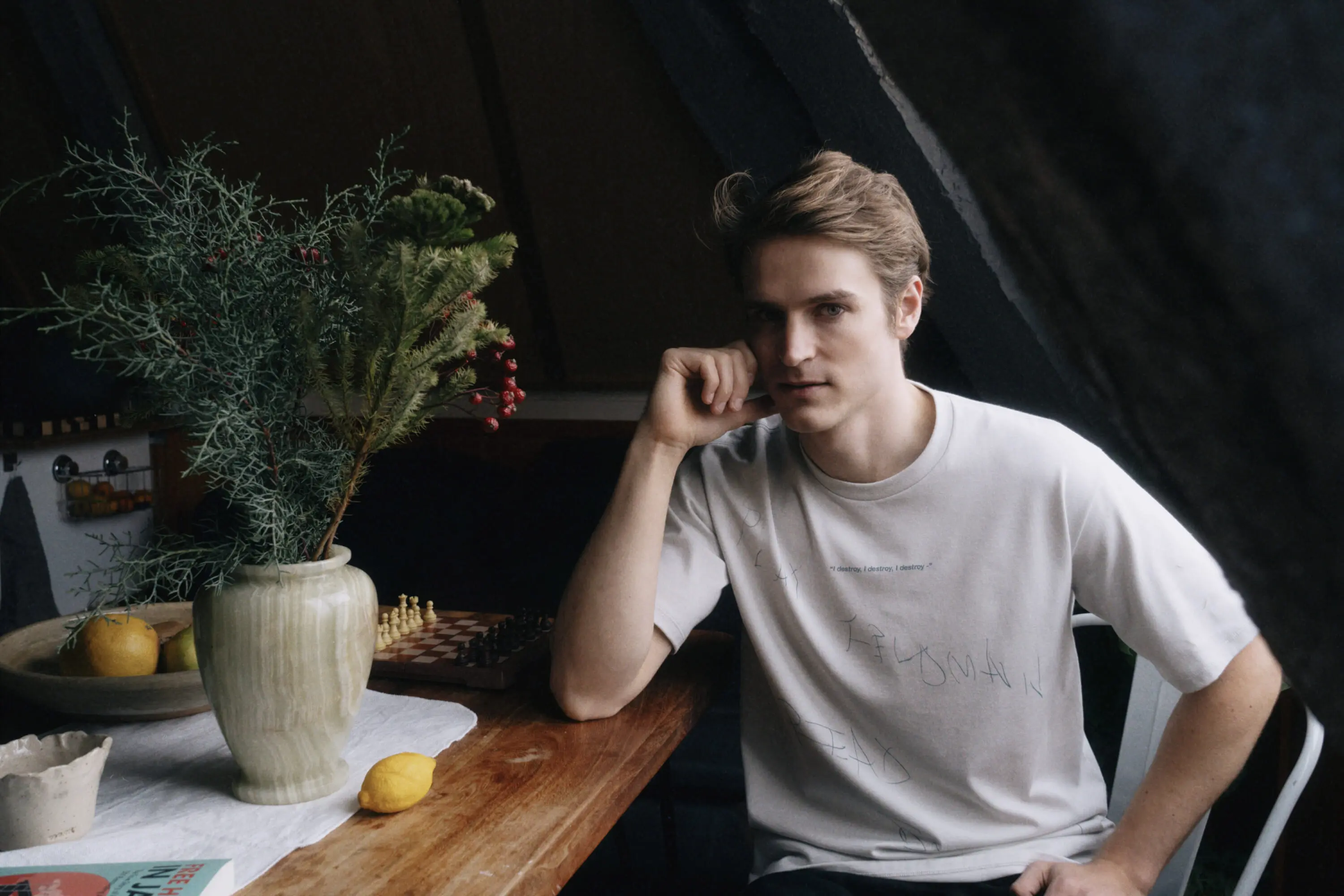

When you interview someone as a journalist, for a certain amount of time, you enter their life and begin to gain small — but significant — insights into what makes them tick. Content creator, YouTuber, social media influencer, professional model, author and housing renovation pioneer Anton Wörmann is a fascinating subject, and over a few months at the tail-end of last year, we spent a significant amount of time together. We first met at Blue Bottle Coffee Roppongi for an interview, then at celebrated menswear brand Lad Musician’s office in Tomigaya, and lastly in one of his charming renovated houses in Sangenjaya for this issue’s cover shoot. He’s a complex man, and because of his multifaceted life, he’s quite difficult to pin down.

We discussed his book and housing career in our first meeting, modeling and fashion in our second and pretty much everything else in our last. Despite being an intimidatingly handsome man, for me at least, he immediately puts everyone he’s with at ease. Friendly, generous with his time, very intelligent and culturally savvy, it’s no wonder Wörmann is very quickly becoming one of Japan’s most recognizable faces and respected business people.

Raised on Renovations

Born in the suburbs of the Swedish capital of Stockholm, Wörmann tells me he has always been comfortable around wood, carpentry and the idea of renovation and renewal.

“I grew up in a 120-year-old house, and it’s kind of normal in European and American culture if you don’t have a lot of money, you do the renovations yourself,” says Wörmann. “It was a very old and rundown house, and my parents renovated it while I was growing up. So, me and my sisters were building our own forts, and that was basically my upbringing. My dad taught us how to use different materials and tools.”

He continues, “Also, in Sweden, we have woodwork in school. And, of course, we have Ikea, which has had a huge effect on Scandinavian furniture. But it’s good to be associated with Ikea as a Swede; they’re a good company. We also have long summer holidays in Sweden, and Christmas holidays. We have a lot more space than Japan. We have a safety net behind us in Sweden with education and health care and a good work-life balance.”

With a professional and high-profile fashion career under his belt that’s seen him work with global mega-brands including Gucci, Calvin Klein and Uniqlo, he first became enamored with Japan when he started to visit as a model several years ago. For many foreigners who come to Japan for short trips, the ubiquitous dread felt upon leaving became a calling sign for the Swede to perhaps rethink his career and refocus on what made him happy.

“I actually first came here for modeling,” he tells me. “I used to live near here (in Roppongi) and my agency (Bon Image) was on the same street. I came three times, once every year for two months. Every time I was about to leave, I felt like I wanted to stay longer.”

Five years ago, Wörmann received his first residence card. Within just a year, he had bought his first property. “I was surprised that for less than $100,000, I could buy a run-down apartment,” he says. “And I was surprised that not a lot of people saw the opportunity and potential of these kinds of places. So, I spent about three months decorating and renovating this house. Not expensive renovations, just making something that was run-down look really nice.”

Putting Pen to Paper

Wörmann began to document his renovation work on abandoned houses, known in Japanese as akiya, on social media and was surprised that there was immediately so much interest from all corners of the world. In just over six months or so, Wörmann reached approximately 1.5 million subscribers spread out over various social media platforms, and it wasn’t long before he started to think about cementing his experiences and advice in a book.

“I was approached by a publishing company, and I didn’t feel that they wanted to do what I wanted to do,” says Wörmann. “When I started to make content about seven months ago, I was always asked the same questions over and over, and I got kind of tired explaining the same answers. So I thought about what would be a good way of teaching people what I do. And then I started taking notes for a few months, and six months later, I had a final product.”

Wörmann shares that, with around 100,000 comments posted to his channels over his six months of publishing content, he had a pretty good idea of what people wanted to know.

His fascinating book, Free Houses in Japan: The True Story of How I Make Money DIY Renovating Abandoned Homes, which has quickly become a bestseller, sees the Swede tackle a multitude of issues with buying akiya in Japan. That the book is a hit is, in some ways, unsurprising, as it covers every legality and bureaucratic step while also providing suggestions on how to research and sharing more general advice and experiences about living in Japan and learning the language: Japan and DIY seem to be of perennial fascination to many across the globe.

Wörmann’s absolute respect for Japanese artisanship comes through in the book and when we speak in person. He says of his mainly Japanese partners, “Japanese carpenters and artisans really are world-class. I do have some foreign friends that help me out (with the renovations), but the main carpenters are all Japanese.

“Kazuki-san, one of the Japanese carpenters, is phenomenal. He doesn’t use nails; it’s so incredible to watch him work — and the way he teaches me as well. We have formed a great friendship and a good partnership.”

Anything Is Possible

Japan’s housing market has been gaining a lot of social media attention lately with the rise in interest in jiko bukken (stigmatized properties) and increasing house prices in the capital, especially in the more affluent wards such as Minato-ku. Wörmann, however, has very much found his own niche, and akiya have become, seemingly overnight, a media and cultural phenomenon.

“There are 10 million abandoned houses right now in Japan,” Wörmann tells us. “And in Setagaya, there are roughly 50,000 houses available.” Even so, Wörmann says that few Japanese companies are involved with akiya.

His lasting advice for potential buyers of akiya is pretty straightforward, and it encapsulates his own experiences of becoming entrenched in Japanese culture and respecting the people and the areas in which you live or want to live.

“I wouldn’t really recommend people buying houses here from abroad, but I would suggest that they come here, spend time here. There are so many abandoned houses that if you immerse yourself for a time in a specific area, then you will know more, and people will tell you things about the area.”

When I leave Wörmann, outside his Sangenjaya project and after the cover shoot, I’m reminded of his fellow Swede, the famed writer and playwright August Strindberg, who wrote in A Dream Play, “Everything can happen, everything is possible and probable. Time and place do not exist; on an insignificant basis of reality the imagination spins, weaving new patterns; a mixture of memories, experiences, free fancies, incongruities and improvisations.”

This very much encapsulates everything about Wörmann, from his attitude toward Japanese culture and strict modeling regime to his renovation projects and social media presence. Never stop, never become complacent and always move forward to the next project with a positive and respectful attitude.

More Info

Follow Wörmann on Instagram at @antonwormann and @anton.injapan and on YouTube at @antoninjapan.