Everything comes at a price. And throughout Japanese history, that often included the horrific price of a human life. Sometimes, many lives. From ancient times to honestly not that long ago, the people of Japan were willing to kill and die for things like serving a sovereign in the afterlife or to help make a sturdy bridge. This is the dark history of Japanese human sacrifices.

Mausoleum of Emperor Suinin, Nara Prefecture

On Feet (And the Rest of the Body) of Clay

According to the Kojiki, the legendary Emperor Suinin was 10 feet, 2 inches tall. His dad once defeated an enemy so hard that the opposing army all soiled themselves out of fear. And, he reportedly put an end to a gruesome funeral practice.

Both the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, Japan’s two oldest texts, stated that after the death of Suinin’s brother, Yamato-hiko no Mikoto, the royal tomb was customarily fenced off with the prince’s attendants, who were buried alive up to their necks and left to die. Many survived for days, wailing while being taken apart by wild dogs and birds.

Finally, Suinin couldn’t take it anymore and, according to Book VI of the Nihon Shoki, declared: “It is a very painful thing to force those whom one has loved in life to follow him in death… From this time forward, take counsel so as to put a stop to the following of the dead.”

However, many royals still wanted someone to do various things for them, such as their cooking and laundry, in the afterlife. So, one Nomi no Sukune suggested replacing live sacrifices with human-shaped haniwa clay figures.

Haniwa figures predate Suinin, but it’s from around his time that we start seeing tombs guarded by clay humans. They were the work of around 100 master potters that Sukune summoned from Izumo.

Incidentally, this was the same Nomi no Sukune who invented sumo during a match when he broke his opponent’s back, giving the area where it happened the descriptive name “Koshioreda” (The Field of Broken Backs).

While the account should be taken with a burial-mound-high pile of salt, the Chinese text Sanguo Zhi (The Records of the Three Kingdoms), written in the 3rd century CE, mentions the legendary Queen Himiko and how 100 of her servants followed her to the grave. However, there was no mention as to whether they did it willingly or not.

Clay Haniwa in Miyazaki Prefecture

Engineering of the Dead

Despite apparently living to the ripe old age of 109, Emperor Nintoku is generally accepted as a real historical figure who was known for his kindness and good deeds. This is despite ordering the deaths of two men because of a dream.

In Book XI of the Nihon Shoki, the sleeping Nintoku was visited by a god telling him that Kowakubi from Musashi and Koromono-ko from Kawachi had to be sacrificed to the deity of the Kita River (in modern-day Shiga and Fukui prefectures) to stop it from flooding.

Koromono-ko found a way out of it without angering the gods, but Kowakubi, crying and trembling, accepted his fate and drowned himself, calming the river and strengthening its embankment.

The story reads as a celebration of cleverness and quick thinking, but the people back then got another lesson out of it: human sacrifices work. The incident is now regarded as Japan’s first hitobashira (human pillar): the practice of incorporating human deaths into the construction of bridges, castles, river embankments and so on.

Sometimes, people were killed and placed within, say, the walls of a tunnel to keep it from collapsing. Others were killed and placed in coffins that were sunk near dams and bridges. They were the lucky ones. The unlucky ones were buried alive in the foundations of homes and castles to protect them from fires and other calamities.

In Tohoku, the practice survived for centuries but eventually moved away from human to animal sacrifices.

“In some cases, these sacrifices gave name to small castles,” says Tohoku expert Doctor Nyri A. Bakkalian. “This is why a bunch of the local fortifications in the Sendai domain were nicknamed Gagyu-jo, or bowing ox castles, because they’d apparently been constructed after the live burial of an ox.”

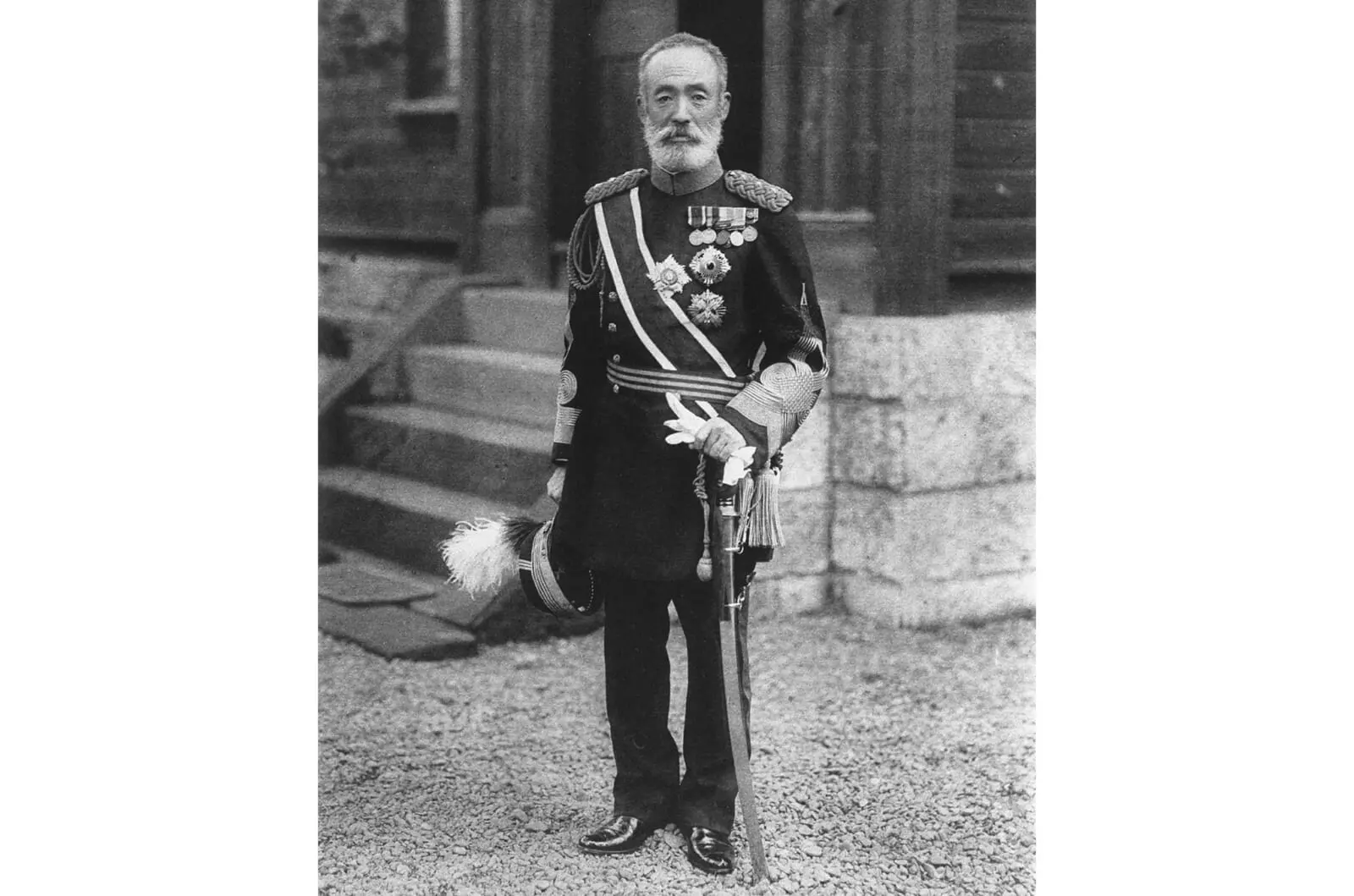

Portrait of Nogi Maresugi, shortly before his suicide in 1912 | Image c/o National Diet Library

Following the Dead Right Into the 20th Century

There have been stories of hitobashira surviving well into the 20th century, but many of those accounts remain unconfirmed. No such luck with junshi, which is technically a self-sacrifice. It’s a form of ritual suicide performed by a retainer after the death of their lord. It was big during the Edo period, a time of near-constant peace.

Before then, when Japan was constantly at war, the samurai’s main job was to stay alive. But after peace rolled in, the samurai started thinking and considering what it really meant to be a warrior when there was no war. They concluded that upholding the ancient tradition of junshi — following the dead — was the best way to prove they were still samurai.

The last recorded example of junshi comes from a little over 100 years ago, when General Nogi Maresuke committed seppuku after the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912. To put that in perspective, that was the same year the electric blanket was invented and the first electric traffic light was developed.