The events of the TV series Shogun are directly responsible for the modern Japanese terms for gravity, heliocentrism, national isolation and other ideas. Mostly based on real events with just the names changed for some reason, Shogun opens with a Dutch ship arriving in Japan, marking the first contact between the country and the Netherlands. After Portugal fell out of favor with Japanese authorities, the Dutch—having gained a foothold in the country — helped suppress a rebellion of Japanese Christians. They subsequently became the only European people that Japan would deal with. In 1641, the Dutch East India Company set up a factory on the island of Dejima off Nagasaki, and for the next 218 years, it was Japan’s primary source of information about the Western world, its history and its science. This is where Shizuki Tadao entered the scene.

Hanyo Nagasaki Map | Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture Collection

Shizuki Tadao: Polyglot, Scientist, Possible Misanthrope

Born to the Nakano merchant family, the man who’d forever change the Japanese language was adopted by the Shizuki family and became a Dutch interpreter (known as a tsuji) sometime in the 1760s. The clan had been facilitating trade on Dejima between the Netherlands and Japan for seven generations at that point. Shizuki entered the profession in 1776 but seemingly quit just a year later, citing poor health.

However, based on the latest research by the likes of Professor Ann Jannetta at the University of Pittsburgh, he might have continued in his role as a tsuji until 1786. His invalid status is also suspected, and the leading theory is that while he stayed involved with the interpreter profession, he mostly kept to himself because he focused on scientific research in his spare time and because he was just a generally unsociable person. When it comes to great minds, the two often go hand in hand.

Shizuki was unquestionably a great mind. Living in Nagasaki, he had access to Dutch translations of the bulk of European scientific research, from Nicolaus Copernicus to Isaac Newton, and he set out to translate it all into Japanese.

There was one problem, though. The Japanese language simply lacked many of the words found in the treatises, forcing him to invent them from scratch. His creations included juryoku (gravity), kyushinryoku (centripetal force) and enshinryoku (centrifugal force). While the last two aren’t that frequently used, they are still standard Japanese today, with juryoku being a very common word.

Also, the use of the -ryoku suffix — from the Sino-Japanese reading of the kanji for “strength” to indicate “force” — has laid the foundation for future developments of Japan’s scientific lexicon. It felt right because whatever Shizuki translated, he tried to understand first… at least to an extent.

Yushi Ishizaki | Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture Collections

Using the Wrong Equation To Get the Right Answer

Like many educated men of his time, Shizuki also spoke and read Chinese, which somehow clouded his studies. While he did seem to understand the principles of Newtonian mechanics and planetary motion, he approached them from a Neo-Confucianist and Taoist perspective.

For instance, he explained the electromagnetic force as an accumulation of qi (the life energy making up the entire universe in Chinese cosmology) and laws of attraction through the prism of Yin and Yang. His focus on Chinese cosmology also most likely influenced his decision to translate “heliocentrism” as chidosetsu (the moving Earth theory) — another common Japanese word that kids today learn in school.

None of these translations were wrong, but many stemmed from metaphysical understandings of natural phenomena. Perhaps the greatest lesson that Shizuki can teach us is that knowledge isn’t transferrable because his true talent quite obviously was in languages and not science.

Shizuki was reportedly the first Japanese person who understood Dutch in Western grammatical terms. Before that, the trend was to sort of shoehorn Dutch into a Japanese or Chinese grammar framework. It was sufficient for business transactions on Dejima, but it hindered the understanding of scientific texts and, consequently, scientific thought. Shizuki changed that. He also changed how we talk about Japanese history.

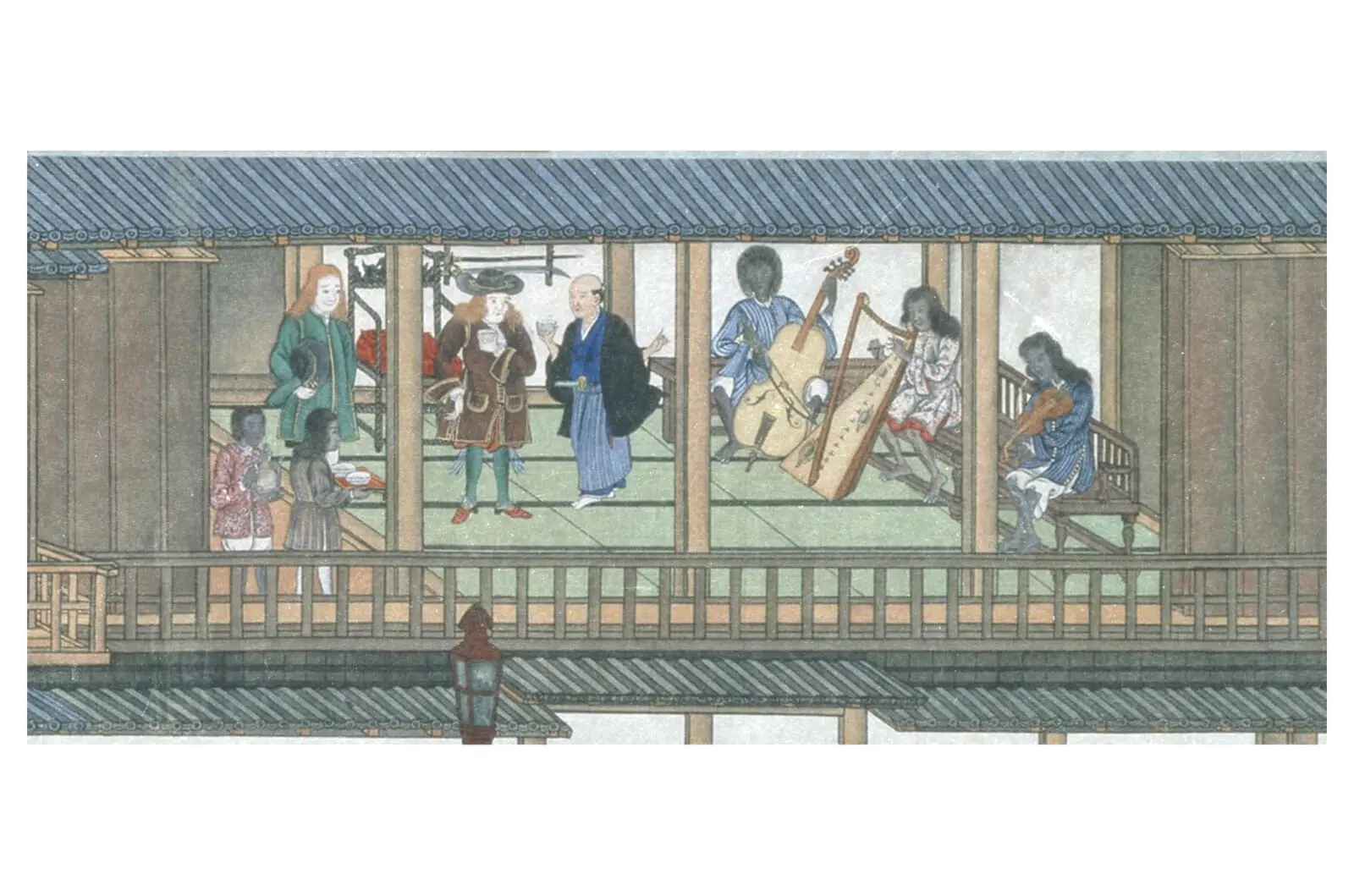

Engelbert Kaempfer, Detail from cartouche of Regni Japoniae Nova Mappa Geographica (1730) | Wikimedia Commons

A Country in Chains

The early 17th-century policy of the Tokugawa shogunate that shut Japan off from the outside world except for Dejima is often described by its Japanese name: sakoku. Typically translated as “national isolation,” the word is actually made up of two characters: “chain” and “country.”

This too was an invention of Shizuki while he was translating an appendix to Engelbert Kaempfer’s The History of Japan. The original didn’t use the word “chain” so the translation may indicate what Shizuki really thought about the policy. It’s hard to think of a “country in chains” as anything good.

However, according to Escape from Impasse: The Decision to Open Japan by Mitani Hiroshi, Shizuki’s notes show that he thought isolationism was great and that he mainly translated the text to make readers feel pride in being born Japanese. His attitude wasn’t that Japan was closed off from the rest of the world, but rather protected from it.

While we may deplore that, this was the prevailing thought in Japan at the time, and it definitely helped popularize Shizuki’s works. Eventually, it helped Dutch studies spread beyond Nagasaki to Edo (modern-day Tokyo), advancing the course of not just physics but also medicine and other sciences. Once again, we see that it’s possible to use the wrong equation and get the right answer.