Photography can be many things. Snapshots of streets and its multifarious inhabitants, portraits from the past, dramatic landscapes and cityscapes that burn bright with promise. Jörgen Axelvall, a resident of Tokyo for more than a decade, has been a prolific chronicler of his own story, a visual narrative which spans his childhood in Sweden to his formative years in New York working as a photographic assistant for legends like Ellen von Unwerth to his days in Tokyo working as a professional lensman on a disparate array of projects which have received a spectrum of accolades.

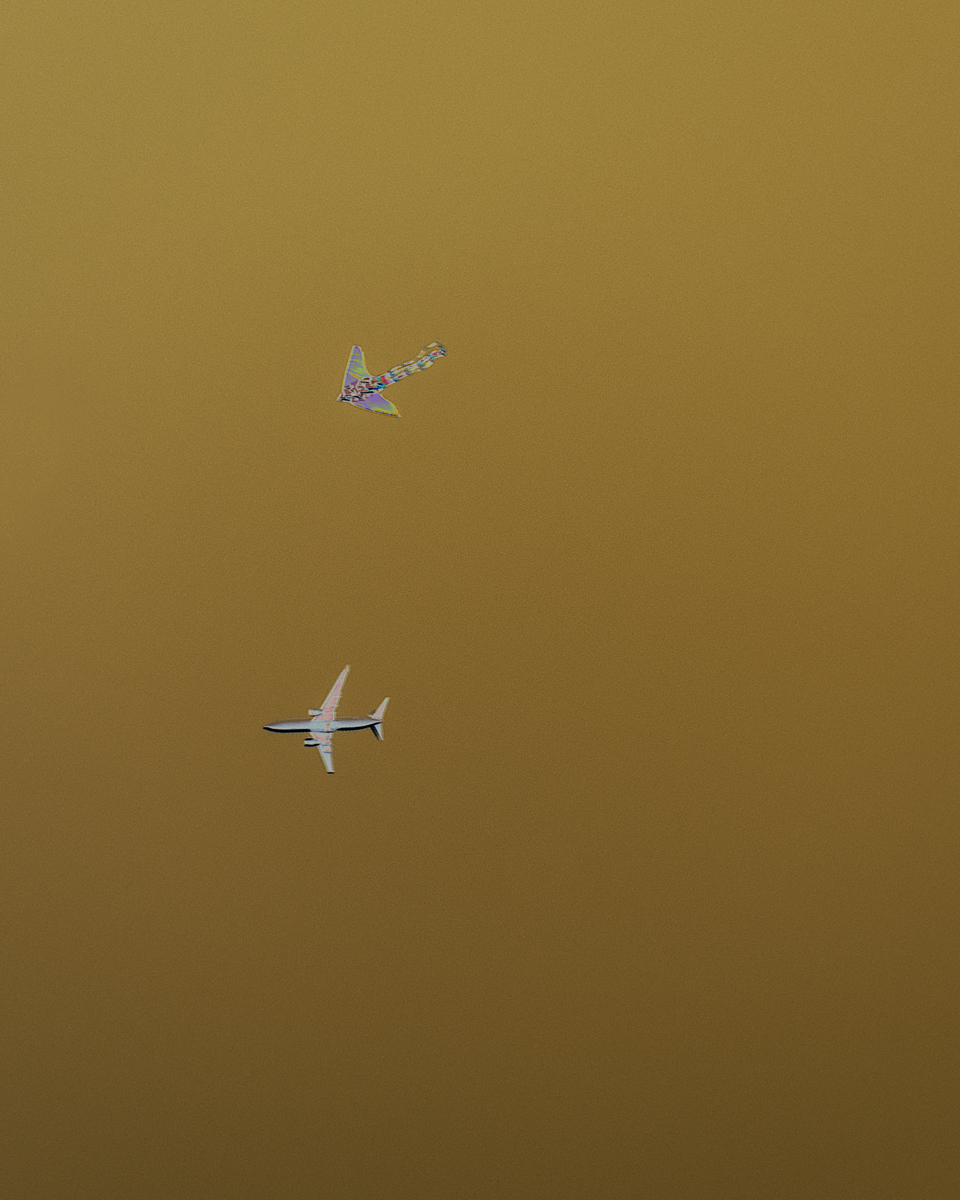

Humble, with a preoccupation with the male form, his work can be categorized as fine art but also realism, an instantaneous frame of contemporary life in the Japanese capital. Axelvall has been dealing with cancer over the last few years and his struggles and bravery have had a huge effect on his work. His latest exhibition, Looking Up, showing at Shinjuku’s Ken Nakahashi gallery until June 12, is a temporary shift away from people and bodies towards an abstract and philosophical look at the sky and the possibilities of travel, both in a physical and metaphorical sense. I spoke with Axelvall over Zoom as he had just returned to Sweden after he attended the exhibition opening reception in Tokyo.

Your new exhibition and book Looking Up can be considered a departure for you in terms of subject matter. Can you explain more about this?

It was during the pandemic lockdown and there was little interaction. It wasn’t even on the radar to find people to photograph. The model agencies and everything else was closed. How did you meet people for a year and a half? It was very much a pandemic project. I was kind of lonely. We didn’t meet each other, friends couldn’t see each other.

And the airplanes were there. What the fuck should I do? I’m not going to any openings, any bars, or socializing whatsoever, so it was sort of like, this is available (planes) so this is what I’m going to do.

But on another level, you always want to expand what you do as an artist. You get bored and don’t want to get stuck in the same world. I’m sure there are followers of mine, collectors who would like me to do the same thing over and over. It goes for all artists. If they see something they really like it’s hard to change. Other photographers have found it difficult to do new things. Unless you’re someone like Picasso.

Departure? I’m not sure that’s right. I’m not done with people. I’m coming right back to that subject in the next exhibition I’m doing with a painter called Yukimasa Ida. The show is in December at the Maki Gallery in Tennozu Island. It’s actually the biggest gallery in Japan. It’s huge and exciting. So perhaps me focusing on the sky and planes could be called an expansion rather than a departure.

What does the airplane signify to you? In your introduction essay to your book, you seemed to have been irritated by them at first.

The planes frustrated me at first. I was shocked at them flying so low right over the city every day. Somewhere in my consciousness it brought back 9.11. Because I was in New York and saw the towers fall down. I didn’t go into it in the exhibition notes because it was the pandemic and I had cancer. But now it also signifies the war in Ukraine in some ways. It’s like news images. And I guess they (photos) signify the possibilities I was missing out on. So, there was frustration.

And when the cancer struck the images became almost heavenly. That’s why the planes in the photos are so small sometimes. In the book there are some images which are very architectural, obviously shot in Tokyo and intrusive. It’s right there on top of you. It’s quite transcending. It became a symbol. A modern angel perhaps?

You have been fighting cancer, successfully, over the last few years. How has this journey affected your work as a photographer?

Because I had cancer, it gave me something to do other than popping pills. This project was something I could actually handle. Due to the pandemic and the state I was in I couldn’t interact with many people. My immune system was fucked and I had no energy. I couldn’t even pick up my phone to book a shooting. I couldn’t go out. I was hospitalized. This was available from my balcony, it was available from my hospital ward. Some of the pictures I took straight from my 14th-floor window in the hospital. Others were taken from the roof of my house and the balcony of my house. I guess you take what you can get.