Story by Katie Cork, Photos by Dov Friedmann

Hirotake Yano used to have an old Toyota Celica, but he recently changed this for a smaller car. He drives himself to his office in an unimpressive two-story building. There is no receptionist. The conference room is usually filled with boxes and samples from the warehouse or from visiting salesmen.

His office, tucked away in a corner, does not have a large window with a view. You would never guess from looking at him that Hirotake Yano is the founder and owner of Daiso Industries Co., Ltd., and the building is the headquarters of an organization that last year turned over ¥202 billion ($1.69 billion), and has around 2,000 stores across Japan.

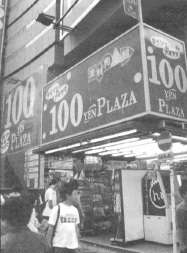

For Daiso Industries is the company behind the “100 Yen Daiso” Plazas. From humble beginnings, selling out of the back of a truck driven by his wife, Yano has survived the economic downturn of the last decade to become one of Japan’s success stories of the 1990s and beyond. Unlike 99-cent stores in the U.S. or £1 shops in the UK, which are generally found in poorer neighborhoods, ¥100 stores sit side-by-side with expensive department stores and trendy boutiques that sell melons for ¥13,000 each and designer label clothes for considerably more. The company continues to expand at a rate averaging 30 new stores a month.

Daiso, which means ‘big warehouse,’ is based in Hiroshima, Yano’s home city. While he insists that he is just “an ordinary man,” the company he founded is far from ordinary. There is no business plan, no budget, no company meetings and no quarterly results. He doesn’t know how many outlets there will be by the end of the year. If increasing the number of stores strengthens the company then he will continue to open more, he says.

It has certainly strengthened the company over the past six years. Turnover has increased nearly ten times since 1995, and Daiso stores now stock more than 40,000 lines.

For an organization that is growing as fast as Daiso, a lack of planning would appear to be dangerous, but Yano’s philosophy has always been to live from day to day. “I wait for my destiny to lead wherever I go,” he says.

Hirotake Yano was born Koro Kurihara in 1943. He comes from a large family of five brothers and three sisters. He changed his name when he married Katsuyo Yano because “Yano sounds better than Kurihara in a business transaction.” His live-for-the-moment attitude comes from the experiences he has had in the past, particularly the bankruptcy of his father-in-law’s fishery, which Yano took over at the age of 26.

“I have failed many times” he says, “and I thought that whatever I tried, nothing was going to succeed. During the inflation era, I thought many times about quitting. It seemed absurd to sell things at a fixed price. But I kept going because I thought there was nothing else I could do.”

Fleeing Hiroshima and bankruptcy, Yano headed for Tokyo with his wife and young son. While he always thought he would be a salesman (“I’m not as smart as my two brothers who are doctors”), his first stint selling encyclopedias ended after just three months when he realized that he was no good at it.

A job in a garbage recycling company proved more profitable, and he was able to pay some of his debts. Moving back to Hiroshima at the request of his father, Yano drifted from one job to the next until he met a mobile merchandiser and started working for him. In 1972, at the age of 29, he established his first store named Yano Store, displaying his goods on a wooden stand.

In 1977 he changed the company name to Daiso Industries and introduced the universal price of ¥100. Why? For no more strategic reason than that having to tag so many different products with different prices was becoming too time-consuming for Yano and his wife, so they decided to make things easier. Why ¥100?

“The ¥100 coin is the minimum limit that the economy and corporate activities can be maintained at,” he says. In 1990 he launched the current chainstore business 100 Yen Daiso.

Despite the lack of planning, Daiso Industries has achieved a level of success that most companies would envy. On a recent trip to the United States, Yano visited similar companies, the so-called 99-cents stores. He was amazed to find that the turnover of the largest of these was less than a quarter of Daiso’s. “In Japan, where prices are supposed to be very high,” he says, “in general we are able to sell products lower in price than Wal-Mart and this fact really pleases me.”

When the company first started, it faced a problem of perception—because of the low price, the products must be of poor quality. Yano set his maximum purchase cost at ¥70, but found that by increasing this cost to ¥80 he could buy superior quality products that sold better and improved the company’s reputation among its customers. Today, with so many product lines, only Daiso’s buyers know exactly how much each product costs.

Quality is now very important. Yano is anxious to stress that his stores do not sell low-quality products. He would like to aim more for the luxury end of the market. As the size of orders increases, the wholesale price drops so that he is able to maintain and increase profit, while buying better quality items.

Even if the perception is that the quality is not as good as elsewhere, at ¥100 most things are seen as good value—especially when a similar product is on sale down the road for five or six times the price. This year Daiso 100 Yen Plazas is introducing a series of 60 maps that retail at ¥800 in other shops. Having said that, last year I loaded my flashlight with batteries from a ¥100 Plaza, only to have them die after an hour of climbing up Mount Fuji. Clothing is another area where quality does not generally come cheap.

Products come from all over the world. A quick rummage through Shibuya’s ¥100 Plaza reveals ceramics from Italy, glasses from the UK, France and Korea, jars from Austria, bamboo baskets from Vietnam and many, many items from China. There are Japanese-English dictionaries, tea towels, teapots, make-up, toiletries, envelopes, pens, fake flowers, fake eyelashes, watches, ashtrays, storage trays, bins and buckets—usually two or three types of the same product to choose from.

Figures are huge. If each store sells 10 wine glasses a day, for example, the total sold each day across Japan is 20,000. This makes a monthly sale of 600,000 units. Daiso imports more through Kobe customs than any single company has ever imported, and orders 30 times as many products from one supplier than the American retailing giant Wal-Mart.

Yano says it’s more than just value he is offering to his customers. “It’s the value and the fun that customers can find in ¥100. They get mental satisfaction from their shopping experience,” he explains.

A quick poll of shoppers shows this to be true. “It’s fun to shop here,” is a frequent comment. My friend Francesca— who considers shopping to be one of life’s pleasures—loves to browse through a ¥100 store to find surprise bargains as much as she enjoys visiting department stores. Nicky says she sees the “cutest things” when she shops there, and usually ends up buying much more than she originally intended.

Impulse shopping is very important and Yano sees getting people to buy on impulse as the strength of the company. “Take glassware,” he says. “Other stores allocate a certain amount of store space for glassware. The customer goes in to buy glassware, compares prices and products and then makes a selection. Daiso customers come in and look at glassware but know that each product costs ¥100. So once they have bought the glasses they came in for, they may start looking around at other things.”

If the company’s future in Japan is not mapped out for Daiso Industries, overseas expansion is already under way. New shops will be opening in Singapore and Taiwan this year, and a joint venture with Ascom in South Korea has already seen 92 stores being opened.

The plan is to move slowly into the overseas market, rather than expand quickly. Yano believes that Daiso is its biggest enemy and he manages the company in a perpetual state of fear. He is scared of becoming greedy, which he says is the cause of so many Japanese companies’ economic difficulties, and tries to keep his principles simple: stay humble, work hard and diligently.

“Business is like climbing a mountain,” he says. “The lesson of climbing a mountain is that there are always struggles and hard times. When you reach the top you get a sense of gratitude towards the mountain.”

And make sure you take plenty of batteries.

External Link: Daiso Japan

Main Image: sebra / Shutterstock.com