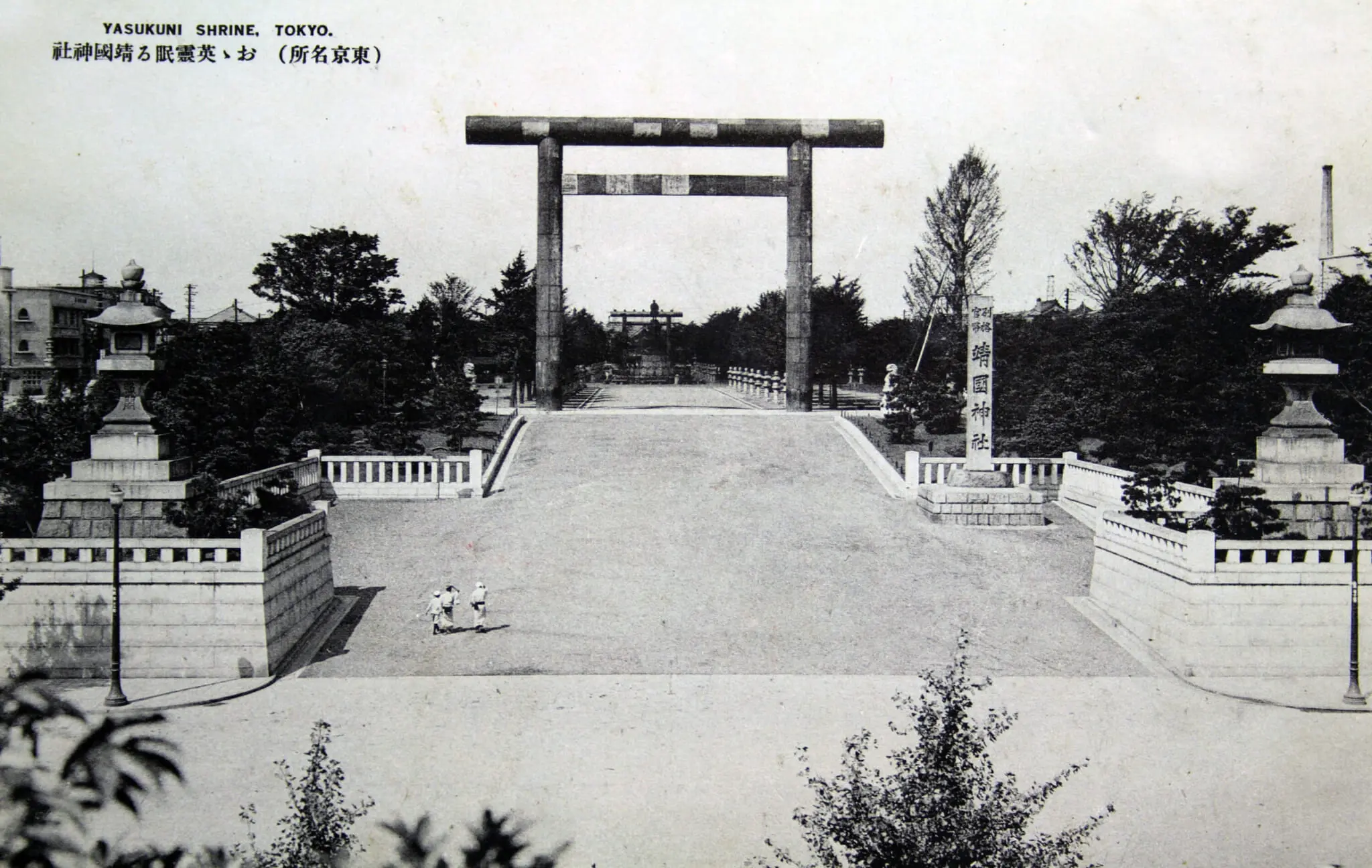

Last week, the kanji character for “death” was found carved into two spots on a stone wall outside Yasukuni Shrine. An elementary school student walking home in Chiyoda ward noticed the markings and alerted a nearby police officer. Investigators revealed that the graffiti had been scratched into the stone using a sharp object. Shrine staff promptly removed the carvings, but the symbolic weight of the act lingers, highlighting ongoing tensions surrounding the controversial shrine.

It’s not the first time this year that Yasukuni has been targeted. In May, the word “toilet” was spray-painted in red on a stone pillar bearing the shrine’s name. The incident was recorded and uploaded. Police subsequently put out an arrest warrant for the Chinese national in the video. Two other Chinese nationals were also placed on wanted lists.

In August, graffiti featuring Chinese characters and Latin alphabet letters, including the word “toilet” in Chinese, was discovered on the same stone pillar. The most recent incident was in a different location, but the target was the same. Japanese authorities have launched an investigation. Property damage, including acts of vandalism at sacred sites, carries a maximum penalty of three years in prison or a fine of ¥300,000.

The Divisive Legacy of Yasukuni Shrine

The graffiti at Yasukuni Shrine cannot be divorced from the larger geopolitical context that has made this site a polarizing symbol within Japan’s cultural and political landscape. Established in 1869 to honor Japan’s war dead, it contains 2.4 million names of people killed in battle, including 1,066 convicted war criminals, 14 of whom were charged with Class A crimes. As a result, it has been transformed into a site of diplomatic friction, particularly with China and South Korea, where memories of Japan’s wartime aggression remain raw.

Every August 15 — the anniversary of Japan’s surrender in World War II — Yasukuni Shrine becomes a focal point of international scrutiny. Visits by Japanese politicians to pay their respects to the war dead often provoke criticism from neighboring countries. This year, the visit of former Defense Minister Minoru Kihara drew condemnation from China, with the country’s foreign ministry stating, “The actions of some Japanese dignitaries regarding Yasukuni Shrine once again reflect the wrong attitude of the Japanese side toward the issue of history.”

Looking Ahead

Sacred sites like Yasukuni Shrine and Meiji Shrine (also recently defaced, though the act was not politically motivated) are not canvases for political protests or platforms for personal outrage; they are integral parts of the nation’s cultural identity and deserve to be treated with dignity. Acts of defacement not only violate the sanctity of these spaces but also undermine the legitimacy of any message they attempt to convey.

Yet, while the responsibility for respect lies firmly with visitors, Japan too must confront the deeper truths these incidents reveal. The defacement of Yasukuni Shrine is a stark reminder of the tensions that simmer beneath the surface of Japan’s cultural and historical landscape.

The country’s sacred sites, particularly Yasukuni Shrine, embody both reverence and controversy. For some, they are spaces of national pride and mourning; for others, they are enduring symbols of unacknowledged imperialist atrocities. These sites should never serve as battlegrounds for protest, yet their contested nature reflects a deeper truth: history, when left unaddressed, seeps into the present in unsettling ways.

The carvings have been erased, but the underlying tensions remain etched in stone. Both visitors and Japan itself must recognize that respecting heritage means more than preservation; it demands accountability, understanding, and the courage to face the past with clarity and integrity.