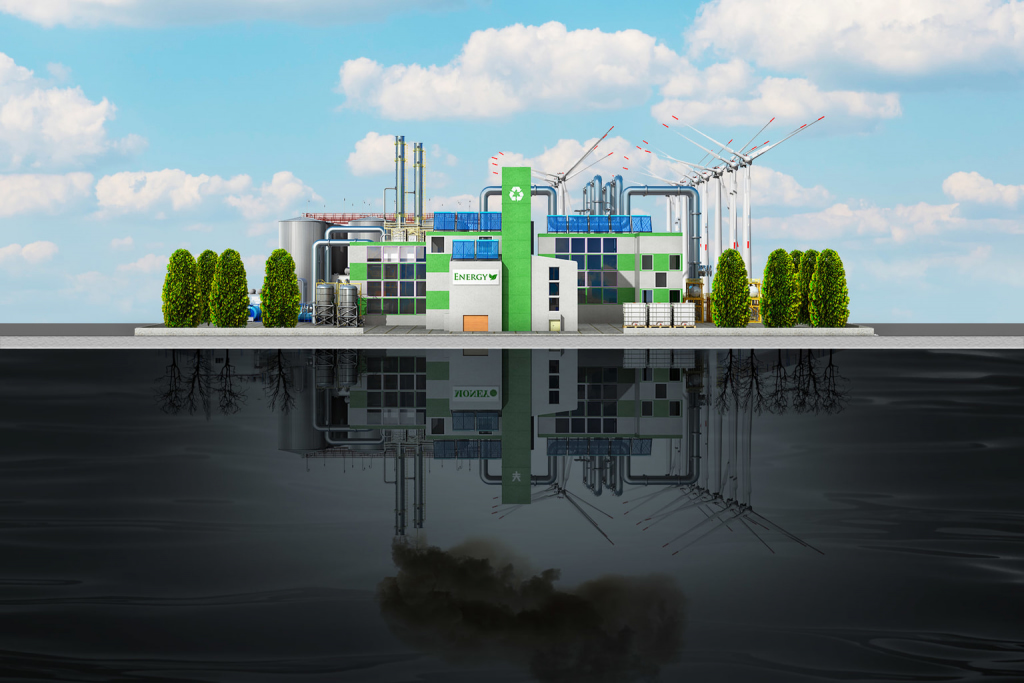

Environmental discourse is never far from a deluge of catchy buzzwords. Company mission statements, product packages and branding campaigns are plugged with words like “sustainable,” “eco,” “forest-friendly,” “recycled,” “net-zero” and “green-certified.” But if you dig under the surface of these smiling, climate-conscious facades, the reality is often more telling. “Greenwashing”, or making unsubstantiated green claims, has become the foil of global climate action. And there’s plenty of greenwashing in Japan too.

Think of some recent high-profile initiatives rolled out in the name of the environment: Starbucks’ climate commitments and the no-plastic-straw campaign, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s pledge for Japan to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050 and JAL and ANA’s much-heralded shifts towards aviation biofuel.

On the one hand, these initiatives sound like positive steps towards a greener, more sustainable future. On the other – perhaps more cynical – hand, they are nice little PR stunts obfuscating larger truths. Or in a word, they’re case-in-point definitions of greenwashing.

Negligible Little Eco Actions

Starbucks may be offering us those soggy cardboard straws now, but its production line is linked to deforestation practices in South America (which are expected to worsen as global coffee demand grows). Japan’s net-zero rhetoric also sounds neat. Yet, it has shown continued support for coal – the biggest contributor to rising global temperatures. It has also invested in 72 individual single-use plastic producing companies in 2020 alone. The major national airlines are promoting the usage of a fossil fuel alternative, while most of their respective fleets are belching carbon into the atmosphere.

In the interest of objectivity, changing to sustainable and environmentally friendly practices is not an overnight fix. Major change often requires a shift in philosophy and a new modus operandi across the board. But humanity has acted with extreme haste in barbecuing its sole celestial habitat — we must act with yet greater haste to undo the damage. Greenwashing simply won’t cut it anymore.

How to Spot Greenwashing

By 2030, the world is on track to drop GHG emissions by 0.5 percent compared to 2010 levels. This is a trifle short, however, of the 45 percent drop necessary to avoid plummeting over the ominous climate tipping point. Moreover, emissions in May 2021 hit 419 parts per million, their highest figure in 63 years of recording data.

This may belie the noticeable shift towards climate awareness at corporate, policy and individual levels. But how do we separate the wheat from the chaff?

According to Damian Carrington in The Guardian, “A good rule of thumb [to spot greenwashing] is whether the proposal actually cuts emissions, by a significant amount, and soon, and whether the proposer is in fact making the climate emergency worse elsewhere.”

Greenwashing in Japan

Tokyo 2020, which is ostensibly aligned with the UN’s 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs), provides a few examples. Among the Games’ Gold Partners (i.e., biggest sponsors) are some of Japan’s wealthiest corporations, including SMBC and Mizuho, whom the No Coal Japan coalition point to as primary greenwashing offenders.

SMBC’s official response to climate change states it will support the “realization of a decarbonized society.” This was reinforced as it became the first major banking group in Japan to rescind funding for new and existing coal-fired power plants in May. SMBC has refused to set net-zero targets which are widely considered an imperative to significantly reduce emissions. However, it is still pumping money into mixed-combustion coal plants leaving it unaligned with the 2015 Paris Agreement protocols.

Last year, Mizuho, another Olympic sponsor and one of the world’s major coal financers, rejected the first climate proposal put to the shareholders of a listed Japanese company. It also partly funded – along with SMBC – deforestation in Malaysia and Indonesia to provide materials for Olympic venues. This undoes much of the goodwill generated by its support for renewable energy projects.

“Save the Planet” Bloviating

Greenwashing, though, isn’t exclusive to Tokyo 2020 benefactors. Uniqlo, one of the world’s largest clothing retailers, signed on to the Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action, yet still operates on a fast-fashion, labor-exploitation model.

Hotels and accommodations across Japan also make various “green” claims, though few have been legitimized by authenticated eco certifications. Only three hotels have squeezed into the standard-setting Bio Hotels group.

For all its “save the climate” bloviating, Japan has done little to lead by example. It recently supported a deal permitting emissions in the shipping industry to rise until 2030. There’s also no nationwide policy to address Japan’s PET bottle consumption. 700 bottles are purchased every second, many of which end up in industrial incineration plants. And though Tokyo recently aligned itself with sea-protection NGO Oceana, commercial whaling is still seen as fair game throughout Japan.

Turning the Tide

It’s fair to say, Japan is not alone. At the recent G7 summit in Cornwall, the UK’s Boris Johnson pledged to reach “jet zero as well as net zero” as he stepped off his airplane from London. Canada’s Justin Trudeau talks a big climate game yet has never shied away from endorsing pro-oil policies. And China’s talk of being a climate leader hardly aligns with the one coal-fired power station it constructs each week.

Having spoken to various climate and sustainability experts over the past year, they all agree on one thing: Ambitious, science-based targets must be set. But unless the targets are enacted upon in a meaningful and transparent way and actually cut emissions equal to or exceeding the parameters set by the Paris Agreement, they essentially count for naught.

Policy and legislation are equally important. A court ruling in May — the first of its kind — ordered Royal Dutch Shell to slash its emissions by 45 percent by 2030. This was hailed as a “cataclysmic day” for oil and gas companies. A recent study in the UK suggested shifting to a four-day work week could reduce emissions by over 20 percent. Applying this model to other post-industrial nations could yield similar results. However, it may struggle to find a foothold in workaholic cities like Tokyo.

The problem is that humanity suffers from a necessity-is-the-mother-of-invention syndrome. We only react to problems when they’ve passed our doorstep and waded into the living room. Only with more accountability, less greenwashing and immediate action can we save ourselves from catastrophe.