Tokyo Calendar Date has been heralded as Japan’s most exclusive dating app.

Created by Tokyo Calendar, an upscale, urban lifestyle publication, the app targets the so-called elite through a stringent screening process akin to Raya, the infamous global dating app for celebrities and influencers. Male members are typically high-income earners, while female members are chosen based on their appearance and social status.

To ensure authenticity, the app requires users to verify their identities with official documents such as driver’s licenses or passports. There are also additional verifications like proof of income and single status certification.

Max Matsuura, the founder and chairperson of entertainment giant Avex Inc., recently announced that he had been accepted. Models like Anna Umemiya also reportedly use it as well. I even spotted well known YouTubers like Kota Fujimoto, or Fuji, as he is more commonly known, from EvisJap using the platform.

But how does it work? And does it live up to the hype? I used Tokyo Calendar Date for a week to find out.

A Rigorous Screening Process

To get onto the Tokyo Calendar Date app, you must pass a two-stage screening process conducted by both existing members and the app’s administration. Here’s a breakdown of each stage:

- Member Review: Current members review your profile, which includes a single profile photo, age and occupation. They decide whether to accept or reject your application. The profile photo is critical, and you can update your profile during the review to boost your chances. The review session lasts 24 hours, but the acceptance criteria is undisclosed.

- Administration Review: After clearing the member review, the administration steps in to check your income, occupation, age and appearance to ensure alignment with the app’s standards. The duration of this review varies, with some results being immediate and others taking up to 24 hours.

I registered on Sunday morning, and after waiting with bated breath for 24 hours, I was approved on Monday.

Credit: Tokyo Calendar

Criteria and Users: Who Makes the Cut?

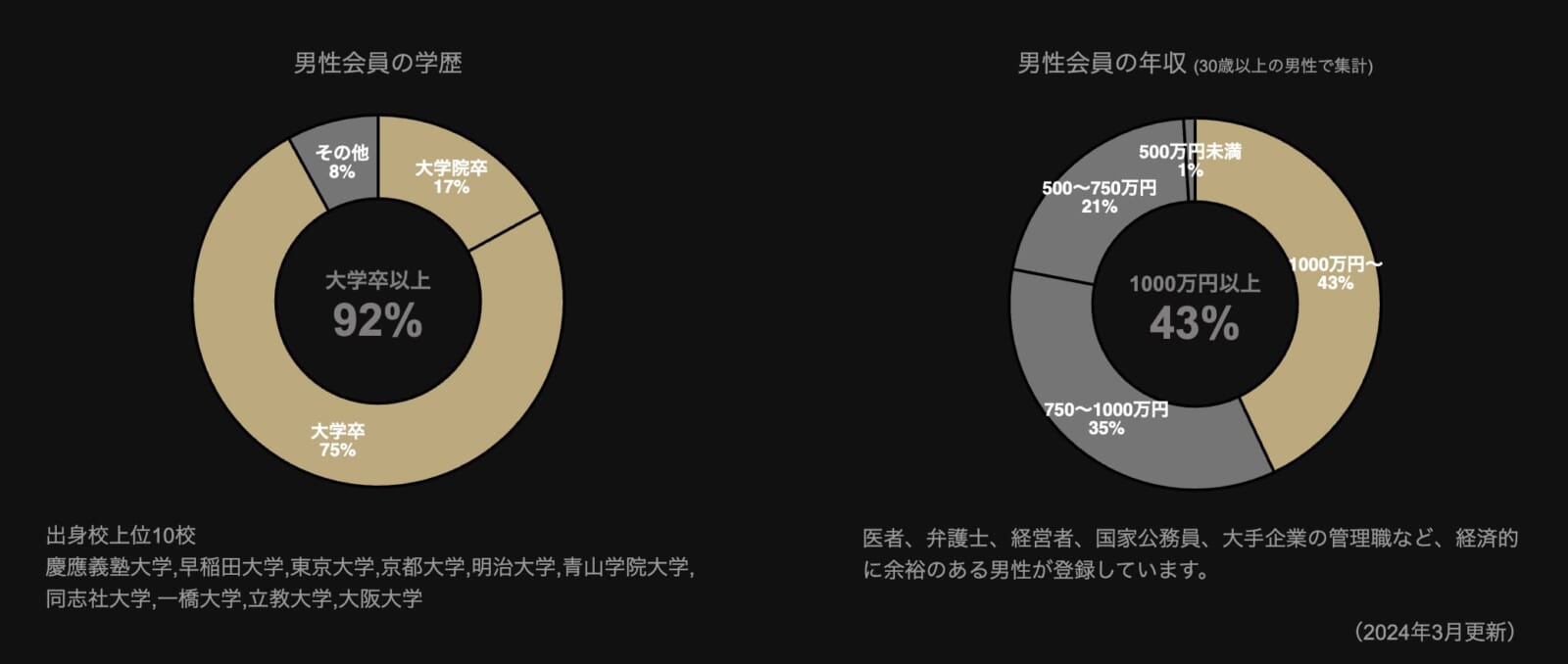

While the exact screening criteria remains a mystery, things can be inferred from the app’s concept and member data. For men, income and educational background appear to be key factors. According to official app data, 92% of male members hold at least a university degree, and nearly half of the men over 30 earn over ¥10,000,000 annually. For context, the percentage of people who have an annual salary of over ¥10,000,000 amounts to just 4.9% of the Japanese population, according to a 2022 report by Mitsubishi UFJ. Men can verify their income by submitting documents such as tax returns, earning a badge on their profile as proof.

My male friend, also a broke college student like myself, registered with me but was rejected. It is estimated that both women and men have a 30% chance of passing the screening process, though the criteria are different.

For women, the emphasis is on appearance and dispositions that supposedly appeal to high-class men. Income and education are less significant. Many registered women are described as elegant, refined or glamorous. Notably, the profile options include specific categories for models and flight attendants, professions considered highly attractive in Japan.

Although joining the app is free, accessing full features requires a gold membership, priced at ¥6,500 per month for both men and women. Gold members can message all matches, while basic members can only initiate conversation if the other party is a gold member. This setup allows many women to use the app effectively for free, as most male users opt for the paid plan.

Credit: Tokyo Calendar

Interacting with Tokyo’s Finest

After unlocking the secret world of Tokyo Calendar Date, I scrolled down past dozens of meticulously curated portfolios as if I were browsing through a high-end magazine.

Square profile pictures were displayed like a gallery in neat rows of two. At the top of the profile was the person’s profession and age, followed by income and the user’s verification status and then their location.

Names weren’t even shown before you clicked on their profiles. Even then, they were random acronyms, initials or clearly fake names. The bios, however, were Proust-level epics, detailing their illustrious careers, the startups they founded and their absurd spending habits. It felt like I was part of an exclusive networking event where everyone displayed their wealth and status.

Some profiles were entirely anonymous. In the place of a profile picture, it would display a black screen with gold script that read “Verified Celebrity User.” These users, deemed celebrities by the app’s administration, receive a celebrity verification mark after another rigorous screening process.

This feature was added to allow celebrities to match freely without being hindered by their reputations and to quell suspicions of catfishing, according to the app.

I could filter profiles by age, location, height, body type — skinny, slightly skinny, normal, slightly overweight, overweight, muscular, curvy — and views on marriage. Unsurprisingly, there was no option for same-sex browsing.

I wasn’t able to control who could see my profile, though. Within my first 30 minutes on the app, I had racked up 50 likes. My matches included a mix of the city’s high-flyers, including doctors, lawyers, executives and even hosts from Kabukicho.

As a 21-year-old, I matched with guys just slightly older than me to men older than my father. While I did receive messages from 50-year-old men, most of my matches were in their late 20s to 30s.

I quickly matched with a 41-year-old divorcee with a verified salary of over ¥100 million placing him in the top 0.03% in Japan, as of 2022. He offered to buy me a vacation home in Switzerland and relocate to New York for me if I married him.

It quickly became clear, however, that not everyone was there for love. Some users sought mutually beneficial relationships, a euphemism thinly veiling the financial nature of some interactions.

Conversations were sophisticated, peppered with mentions of upscale venues and exclusive events. Yet, the transactional undertones were hard to miss.

One conversation with a 46-year-old venture capitalist went as follows:

“Your skin is so soft and smooth, like a newborn baby. Truly an Asian beauty.”

“Haha… thank you.”

“I have about 3,000 bottles of wine in my wine cellar right now. I live in Minato ward. Would you care to help me finish them?”

Another match, a tech entrepreneur, cut straight to the chase:

“How do you feel about an allowance arrangement?”

I had to politely decline.

There were also some rather unique offers. A celebrity stylist waxed lyrical —an entire page-long paragraph —about my long, luscious hair and proposed cutting it and giving me a makeover.

I was wearing hair extensions.

Credit: Tokyo Calendar

The Verdict?

In Japanese dating culture, Tokyo Calendar Date occupies a unique niche. Is it a sophisticated dating platform or a high-end sugar daddy site? The answer seems to lie somewhere in between.

The most glaring difference from Raya lies in the power dynamics between users. On Raya, partners typically meet as equals. In Tokyo Calendar Date, however, the dynamic is clear: the man makes more money and provides for the woman. It’s a return to the 1950s with a digital twist.

This imbalance is highlighted by a section in the profile that asks who should pay for the first date. The options were: the man pays the bill, the man pays more, split the bill, whoever earns more pays, or talk it over and decide. The concept of the woman paying is conspicuously absent.

This setup mirrors broader sociological trends in Japan, where traditional gender roles remain deeply ingrained. Despite strides towards gender equality, societal pressure still often dictates that women prioritize family over career, while men are expected to be the primary providers. This app capitalizes on those cultural norms, offering a platform where financial stability is equated with desirability.

On one hand, the app provides a platform for like-minded individuals to connect. Most people who use this app are aware of its transactional nature and lean into it, which is just as well. The idea that love and affection can be traded for financial security is a concept that resonates in a world where economic stability is increasingly precarious. For many, apps like Tokyo Calendar Date offer a pragmatic approach to navigating modern love.

On the flip side, this pragmatism isn’t without its costs. Genuine emotional connections begin to take a backseat to financial calculations, turning relationships into transactions. Money does indeed matter in relationships, I won’t deny that, but I’d never assigned a dollar value to someone before even meeting them in person.

By the end of the week, matches were just walking paychecks. Their earnings were front and center, not their names, just as the app intended.

As I logged out of Tokyo Calendar Date for perhaps — or perhaps not — the last time, I pondered the broader implications.

Tokyo Calendar Date reflects societal shifts where the lines between love, money and convenience are increasingly blurred. Whether it’s the future of dating or a passing trend, one thing is certain: it’s a world that is as intriguing as it is unsettling.