Shintaro Ishihara, Tokyo’s governor, is known as an outspoken, aggressive politician. Some fear him and many despise him for his controversial stance on matters such as immigration and he is never far from the headlines: whether it be for his involvement in ongoing territorial disputes in the region – particularly his plan to buy the Senkaku Islands – his political policies or his association with Tokyo’s Olympic bid.

Ishihara’s reputation can often divide generations but has taken three elections in his stride since election in 1999 and, whatever people think of him, he is arguably the most important man in what we can all agree is one of the world’s best cities.

On the eve of the IMF and World Bank meetings in Tokyo, Ishihara spoke openly to Weekender about his frustrations with government corruption and the regulation of pornography, his plans for a city he’s proud of and why he doesn’t want Tokyo to become New York.

Literary Beginnings

“When I was young, I wrote a lot of fun novels, basically to earn a living to feed my family,” Ishihara says, after making his entrance from the side door of his office, giving a wide armed “Hello!” and taking off his jacket. “They were interesting, you know, so they were pretty much immediately made into films.”

Ishihara won the prestigious Akutagawa award for his writing at the age of just 23 – before his graduation – and has lived through arguably both Japan’s best and worst times. His 1989 essay, ‘The Japan that can say No’, which pushed for greater confidence and economic independence from the US, was one of his only works to be translated into English (it was originally planned to be a Japan only publication) and first brought him to the attention of the world.

“That book sold around 600,000 copies,” Ishihara says, “after publishing, about half of all Americans became my enemies. But the other half became my true friends.”

A lot of those Americans are in Tokyo this month, with the IMF and World Bank holding their meetings in Tokyo for the first time since 1964, surely a great opportunity to sell Japan to the world?

“Well, I do think its a favourable matter that such a convention is being held here, it will add vibrance to the city,” Ishihara says, and continues by explaining what he thinks delegates will find here. “Every country has its various problems, but when I think about the good points of Japan, of Tokyo, I think of the good public order. In big cities in developed countries, London, Paris or New York, for instance, a vending machine might be smashed or disappear overnight or be robbed of its cash.” But is the idea of perfect order true? “In Japan, of course there are certain crimes but it is absolutely safe here.”

Ishihara says he has made many efforts to improve the look and feel of Tokyo, some controversial and some successful. When we try to push him on the plan, much criticized by animal rights activists, to reduce the number of nuisance crows in Tokyo, he cuts us short, “We tried to get them all but they just keep coming from Kanagawa.”

Pride in the Past

Ishihara is not shy to talk. He tells us that it was he who forced through new transport links to Narita and made Haneda into the International airport it now is. We put it to him that Tokyo has perhaps become a more attractive, international city over the years. “Which part do you mean?” Ishihara asks, laughing a little when we mention the streets of Marunouchi resembling a wide American or European avenue.

“I don’t want Tokyo to be like New York,” Ishihara says. He does appear to take immense pride in Tokyo. “Sometimes I go on a picnic with ambassadors from European countries, we fly by helicopter. In the south of Tokyo, there are islands: brilliant islands and prosperous oceans. We also have mountains: 2,000-metre class mountains in the Okutama area, for example. After all that I let them enjoy a hot spring bath and we relax and my visitors start truly envying Japan, in which a metropolitan city and nature are so close”

A quirk in the dynamic of our conversation is something others have found in the past: that Ishihara likes to frame his political accomplishments with his literary past. It almost becomes a kind of modesty that we don’t expect when he’s talking up Tokyo. We talk about the achievements of Giscard d’Estaing, the French prime minister in the late 1970s credited with bringing culture to the top of the agenda of politics. He talks with admiration of d’Estaing and Malraux, the French novelist and politician.

“When Malraux came to Japan, I stayed with him,” Ishihara says. One of Malraux’s ideas had apparently been to control the colour of neon lights in the city, “he united them into one of two colours so as to clarify and unite the city. Tokyo is in a bit of a mess in that respect. Ugly, isn’t it?”

“I tried to do the same thing here but people insisted on freedom of expression and so on. I still find it troublesome.”

“I also thought that we should not open pornography up to the public but again, the publishing companies became fussy and insisted that it was an interruption of freedom of expression. I don’t think banning pornography is the only solution but I am asking that it is not set out where children can reach it, in convenience stores, for example.”

Ishihara talks of frustration that he couldn’t make all the major differences he wanted to in national government as one of his motivations to push Tokyo forward.

With a couple of years of Ishihara’s term remaining, how does he feel he can change Tokyo? “I am already tired. I don’t really want to continue working for another two years – I would like to die soon.”

Corruption

Ishihara talks bluntly and does look tired when he explains his frustrations. He’s not joking. “Our Gaikan (outer ring expressway) is not completed yet and we must make it happen. That communist, Minobe (the former governor of Tokyo) put a lot of projects on ice. The LDP was also stupid. They changed the governor but never touched the problems.”

“Some of the ill-natured people of Japan are the national government officials, they are corrupt. The same goes for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has messed up our country in conspiracy with the pharmaceutical industry. They have made medicines that are available abroad not available in Japan. Better steroid hormones, for example, will never be able to enter Japan because the political system is manipulated by money.”

Ishihara wants to move away from money, though. “Holding the IMF (and World Bank) convention is good but, after all, there is more to life than money. When we think about what is important for human beings, nowadays, people just say, ‘money, money, money’. But while we are all talking about money, the abnormal climate is accelerating; the abnormal climate has already become our ordinary climate.”

“The Arctic ice is melting fast … In Hokkaido, it used to be impossible to harvest good rice but today it is almost possible to double crop there. The world is far too slow in its discussion of environmental conservation. A conference every three years which only makes a half-step of progress is not enough.”

Ishihara is a talker and despite his age the fire in his eyes burns bright. We could sit with him for hours but time is pretty much up, and for the first time we feel restricted.

Would he like to write a memoir about his experiences when he finally steps aside? “Well, I have many experiences so I would like to write it,” he says, “but, you know, I will be 80 this month. I’m going to die soon, my body is weak. I doubt I can do it.”

by Matthew Holmes (Interview by Kotaro Toda and Ray Pedersen)

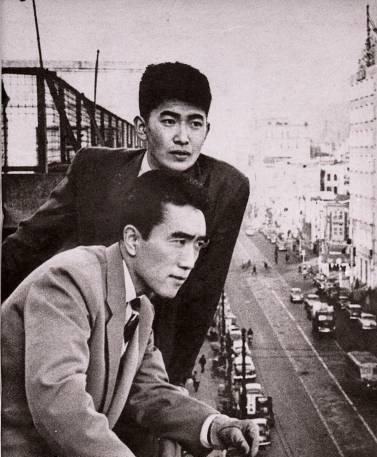

Main image, photo by Norihisa Kushibiki. Inset image: Courtesy The Museum of Modern Japanese Literature