From the questionable conditions of Joe Exotic’s “zoo” to American politicians’ viral accusations against China, hot topics in the age of coronavirus have turned the public eye towards animal cruelty. Covid-19 is thought to have originated in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, a so-called wet market containing open-air stalls of produce, seafood and meat.

Often, these trading centers are good places to get fresh and affordable staple foods, but a few wet markets, including the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, sell live wild animals and their meat. As coronavirus outbreaks were first surging across China and the globe, the Huanan market, where the virus is believed to have jumped from animals to humans, was temporarily closed (it still remains this way) and Beijing banned the trade and consumption of wild animals for food.

Beijing has not banned the trade of exotic pets, and buying exotic pets is no way an isolated activity. Japan is also a prominent participant of the global industry.

Exotic Pet Fair © TRAFFIC

Japan’s Exotic Animal Trade

Indeed, these animals are smuggled into Japan from all over the world. Once they pass the border, they can be sold legally and often make their way as pets into unknowing households, which has facilitated the rise of smuggling rings grabbing for the huge proceeds.

“Crossing the Red Line provides a comprehensive analysis of the country’s smuggling activities and its legal enforcement (or lack thereof)”

Following the wave of international media reports on the illicit trade, TRAFFIC – an NGO that deals with biodiversity conservation and sustainable development – has published Crossing the Red Line: Japan’s Exotic Pet Trade, with the support of the World Wide Fund for Nature Japan (WWFJ). Previous studies have already reported the sale of certain smuggled species in Japan, including otters and reptiles, but Crossing the Red Line provides a comprehensive analysis of the country’s smuggling activities and its legal enforcement (or lack thereof).

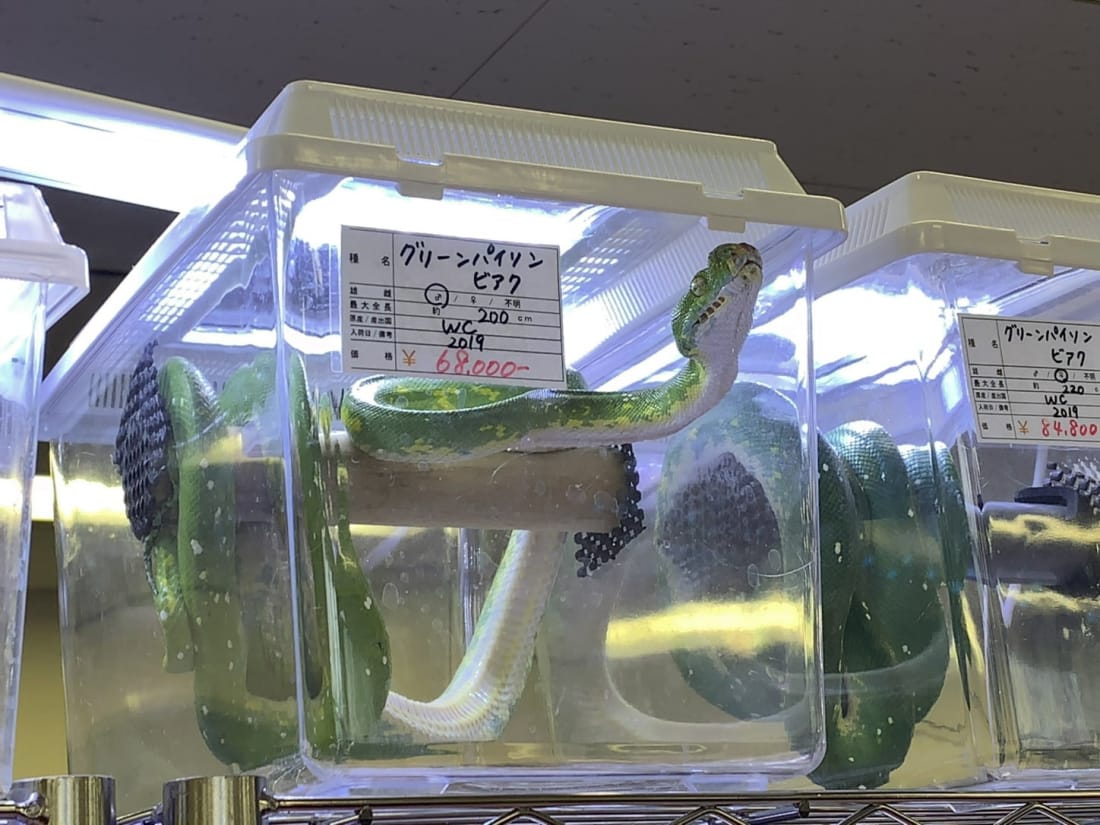

Green Python ©TRAFFIC

The total domestic value of the trade is thought to range from ¥54.1 million to ¥125.6 million (about $500,000 to $1.2 million) – though, like the quantity of illicit imports themselves, global proceeds are likely far greater than what estimates say. Between 2007 and 2018, there were 78 customs interdictions of 1,161 illegal animals in Japan. Since 2007, there have been at least 18 defendants charged in 12 smuggling cases, and the conviction rate is high.

More chilling than these figures, however, is the fact that instances of exotic pet smuggling are rarely detected at Japan’s coast. And to our knowledge, the penalties are light, with relatively short sentences marking all the known cases involving prison time. This contributes to a high recidivism rate for animal smuggling.

Common marmoset ©TRAFFIC

The Spread of Infectious Diseases

Yet, the enormous revenue and its evasive criminal beneficiaries are not the seamiest underbelly of this issue. Japan is a major importer of foxes, owls, turtles, lizards and more. Because they are highly valued, the creatures are continually poached and smuggled and, as a result, risk becoming endangered species.

“Among the exotic animals seized on Japan’s coast, many species are originators of infectious diseases”

Not only does the illegal trade compromise the safety of animal species, but on a global scale it could also threaten entire human populations. Among the exotic animals seized on Japan’s coast, many species are originators of infectious diseases. Japanese law maintains that such creatures cannot be imported into the country, or must be quarantined upon their entrance. Current legislation, however, has failed to inspire much enforcement at the border or quell the nation’s vigorous appetite for slow lorises, marmosets and pythons.

Ryukyu turtle ©TRAFFIC

TRAFFIC found that among the pushers halted by Japanese customs between 2007 and 2018, over half of their animal freight came from Southeast Asia. The rest came mostly from other parts of East Asia. Thailand, mainland China, Hong Kong and Indonesia are the major exporters.

The wildlife markets in exporting countries, often overcrowded, serve as breeding grounds for animal-borne infectious diseases, as well as transit points for potentially disease-ridden animals from the US and Africa. When pets make their way into markets, little stores and homes, they are likely to bring the pathogenic remnants of wet markets with them.

Fruit Bat ©Chris Martin Bahr_WWF

What Can Be Done?

Organizations like TRAFFIC and WWFJ have been stewing over a global solution; the illegal trade routes are so extensive that effective prevention of smuggling (and subsequent disease spread) would require a great deal of cooperation on local and international levels.

Evidently, illegal imports are not being deterred enough. Crossing the Red Line concludes that, in regards to wildlife smuggling, the legal system and law enforcement must be strengthened. Stamping out the more insidious effects, like the bevies of illegal animals in Japan’s legal market, requires entities like citizen groups and the pet industry to get involved.

“The enthusiasm of smuggling networks and the sluggishness of prosecution systems could spell disaster”

In addition to zoonotic disease, this kind of smuggling pervades several international issues. Deforestation increases contact between humans and wildlife, or otherwise drives wildlife to human settlements; global warming has contributed to an increase in the number of animals carrying infectious diseases and led to further habitat changes. With these human activities incurring already dangerous ecological changes, the enthusiasm of smuggling networks and the sluggishness of prosecution systems could spell disaster.

At the moment, the idea of infectious disease prevention may elicit thoughts of self-quarantining, social distancing and ritual mask-wearing, but human and animal health are inextricably linked. The Ebola virus, the Nipah virus and likely the novel coronavirus testify to the dangers of zoonotic disease and the oneness of global health.

Banning crowded wildlife markets is but one step to protecting public health. Avid importers of exotic animals – and the progenitors of environmental disaster – are complicit in disease spread, too. For Japan, scrutinizing customs at the coast could have sweeping consequences.

For more information and recommendations, visit the WWFJ website.

Feature image: Slow loris ©Rob Webster-WWF