IAN PRIESTLEY wonders if Japanese film could be heading for a renaissance

THE GOLDEN age of Japanese cinema was undoubtedly the ’50s, where directors such as Yasujiro Ozu, Akira Kurosawa and Kenji Mizoguchi made films which were not only watched by a large proportion of the local population, but also influenced film makers the world over. The three, with their slower, painterly approach to film making, helped make cinema the art form that it is considered today.

Each decade since has spawned directors now synonymous with their time. The ’60s and early ’70s saw the rise of Nagisa Oshima and Shohei Imamura, so-called new wave directors sponsored by the influential Art Theater Guild (ATG). In the ’80s, although generally considered a time of stagnation after the demise of the ATG and the unwillingness of the big production companies to take risks, Juzo Itami became the critically acclaimed director of his day, with films such as the world’s first “Ramen western”, Tampopo (1986). Itami liked to question the conventional wisdoms of the time — his classic The Gentle Art of Japanese Extortion (1992), inverted the normal portrayal of the yakusa as the latter day samurai. Instead, he portrayed them as bumbling oafs, which ruffled feathers so much that the director was attacked and scarred for life.

A number of new directors have emerged in a

range of genres from horror, to anime and art

house. This has inspired people to talk of a rebirth

in Japanese filmmaking.

Although the early ’90s continued the less than inspiring trend of sticking to the tried and tested, since the mid ’90s a number of new directors have emerged in a range of genres from horror, to anime and art house. This has inspired people to talk of a re-birth in Japanese filmmaking.

Certainly, the heavy Japanese presence at international film festivals such as Cannes and Venice seems to be an indicator of robust health and the, recently established, English language website midnighteye.com devoted to Japanese film, is testament to international interest. The site, as well as providing reviews and interviews, gives details of subtitled releases both in Japan and abroad.

A big difference, however, between now and the ‘50s, is that the critically acclaimed directors of the day were also big draws at the box office. Nowadays, a fair percentage of those films receiving acclaim and attention at international film festivals are not exactly money makers — although there are, of course, always exceptions.

Putting the great global export that is anime aside (which would require — at least — a whole other article) there are several Japanese directors that stand out.

The mid-to late-‘90s saw a number of new directors involved in lower budget, independent productions. Kore-eda was one of them. Afterlife (1998) and Nobody Knows (2004) show how imagination can circumvent the need for big productions. Afterlife recreates a limbo world in a disused factory where the recently deceased are encouraged to choose one moment of their lives to keep forever. Kore-eda’s films are shot like documentaries, and Afterlife was part unscripted and based on interviews, seemingly bridging fact and fiction.

Shinji Aoyama’s Eureka (2000) likewise uses imagination and craft in its sepia take on a road movie with a difference, as the survivors of a brutal hijacking journey through Japan and rediscover a reason to live.

While Aoyama and Kore-eda might fit with relative ease into the art house category, Takashi Miike defies description. His films range from the horror (and I mean horror) of Audition (1999) to the “musical” — The Happiness of the Katakuris (2001). Imagine the Rocky Horror Picture Show set in a Japanese ryokan, and throw a zombie in for good measure.

The ubiquitous Takeshi Kitano is, of course, one of those notable exceptions: a director who can make critically acclaimed art house films which also do well at the boxoffice. His cop/gangster films such as Sonatine (1993) contain an almost surrealistic amount of violence. Takeshi’s portrait of the loner going out in a blaze of glory is one of those Japanese traditions in the arts, like love suicides, which have always gone down well with local audiences. In recent years, Kitano has widened his range with films like Dolls, (2002), which interweaves three love stories, and more recently, his acclaimed version of the samurai classic Zatoichi (2003).

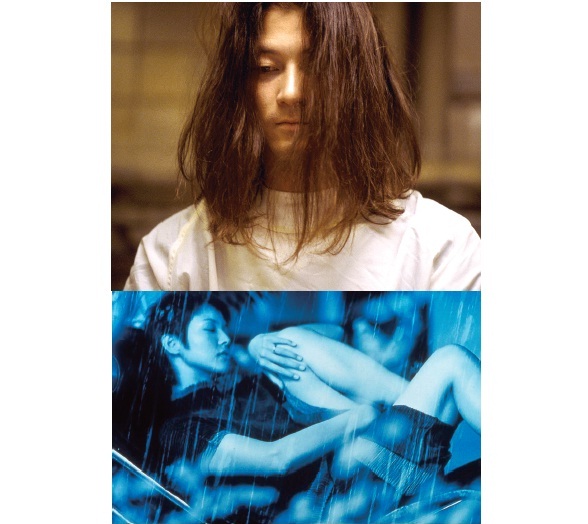

Like Takeshi Kitano, Shinya Tsukamoto is a director you just can’t pin down. He first made audiences sit up and stare in 1989 with Tetsuo: Iron Man. Shot in black and white, the film mixes animation and acting as the human body and a machine become intertwined. He remains on the cutting edge, too — his recent move into more erotic terrain, the Robert Mapplethorpe inspired A Snake of June, drew acclaim at the 2002 Venice film festival.

After anime, the genre most associated with Japanese filmmaking is probably horror — thanks to the export of Hideo Nakata’s Ringu. And, with the success of Takashi Shimizu’s The Grudge (based on the original Japanese film Ju-on: The Grudge, also made by Shimizu) at U.S. box offices last year, it’s a genre that looks like its going to just keep on growing.

Further information: midnighteye.com. For movies with subtitles, try www.amazon.com.