Japan’s Annual Nengajo Frenzy

by Benjamin Freeland

Expatriates in Japan who, due to either monetary or employment constraints, are unable to go home for the holiday season can take solace in the fact that they get to experience the country at its festive best in the form of the o-shogatsu (New Year) season. As with most Asian countries, New Year is without rival among Japanese holidays, and in a manner reminiscent of Christmas in the Western world, Japanese New Year is characterized by a mix of solemnity (the obligatory shrine visit) and gleeful abandon (the muchanticipated otoshidama money for children and the traditional New Year’s games), with similar importance accorded to traditional New Year’s food, decorations and seasonal greetings in the form nengajo (New Year’s cards). This last tradition is perhaps the most intriguing of Japan’s many New Year’s rituals, due both to its enormous scale (over four billion cards are exchanged annually) and the manner in which it neatly captures the country’s devotion to punctuality and protocol and its uncanny capacity for blending the ancient with the ultramodern. For foreigners wishing to embrace the spirit of o-shogatsu, nengajo are a great starting point.

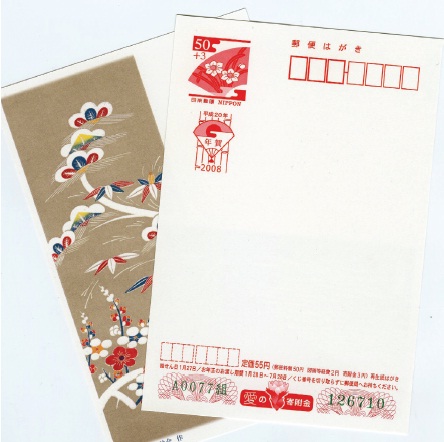

Exchanging New Year’s well wishes in card form has been customary in Japan for centuries, and the modern nengajo dates back to the inauguration of the national postal system in Japan in 1873. In this pre-mass communication era, the custom not only served as a way of wishing loved ones a happy new year but also served as a means for people to inform distant relatives and friends that they were alive and well, and as such, it is still considered poor taste for people who have lost family members during the year to exchange joyful nengajo. Today’s nengajo postal system dates back to around 1899 and grew rapidly in popularity, and in 1949 post offices began issuing the now-popular otoshidama-tsuki nenga hagaki featuring lottery numbers, for which winning numbers are chosen every January 15 and prizes (typically home electronics and package tours) can be claimed at post offices thereafter. While the advent of the internet has led to the popularization of e-nengajo, the traditional exchange of New Year’s cards in Japan is as popular as ever, thanks in large part to the remarkable efficiency of the country’s postal service, which guarantees the delivery of some four billion cards on Jan. 1 on the dot, routinely hiring part-time students in order to fulfill its onerous annual pledge.

While Japan’s myriad rituals and formalities can seem daunting at the best of times, nengajo exchange is a relatively straightforward affair, and serves as a refreshingly easy way for newcomers to ingratiate themselves to new Japanese friends, colleagues, employers or in-laws. While many prefer to design their own nengajo, those with innumerable friends and relatives and limited time will invariably opt to order pre-made cards through post office catalogues, for which orders are accepted from mid-October until Dec. 14. Prominently featured on most nengajo is the forthcoming year’s junishi (Chinese zodiac animal), and with the Year of the Rat fast approaching, rat and mouse-themed designs (including ones featuring the country’s favorite rodent pair, Mickey and Minnie) predominate among this year’s ready-to-order nengajo. Pre-made card sets range from batches of ten to 200 and start at ¥2,850 for black and whites and ¥3,850 for color. For those preferring to design their own, plain white cards generally sell for ¥50 a card at stationary stores, post offices and convenience stores. Hand-designed cards typically feature family photographs (including photos of weddings and/or new babies) and are frequently embellished with print-club photos, stickers and hand-drawn illustrations. Post offices provide specially marked mailboxes between Dec. 15 and 25 for nengajo, guaranteeing their on-the-dot delivery on Jan. 1. As with pretty much all Japanese traditions, there are certain protocols to observe in relation to nengajo. Customary nengajo greetings include the standard New Year’s greeting “あけましておめでとうございます” (Akemashite omedetou gozaimasu) as well as the more formal variant “謹賀新年” (Kinga shinnen) or the more flowery “新春のお喜び申し上げます” (Shinshun no oyorokobi o moshiagemasu), which translates to “Wishing you happiness for the coming spring.” As it is considered disrespectful to the recently deceased for their immediate family to distribute nengajo, post offices provide simple, unadorned cards to send to would-be well-wishers, informing them of the loss and advising them not to send joyful cards out of respect for the deceased. Should you inadvertently send a nengajo to the family of a recently deceased person, it is customary to first apologize and then, after Jan. 7, send a winter greeting card in which one expresses their sympathy, making sure to avoid using the kanji “賀” (ga, which means “celebration”). Should you receive a nengajo from a person whom you neglected to send one, it is considered appropriate to send a belated salutation on Jan. 6, bearing the formal greeting “寒中お見舞い申し上げます” (Kanchu omimai moshiagemasu), which roughly translates to “Take care in the winter weather.” As with most Japanese traditions, however, foreigners are generally not expected to be familiar with all these intricacies, and any sort of observance of this tradition on their part is likely to be met with surprise and delight.

On the surface, Japan’s annual year-end card exchange frenzy can appear a rather daunting affair. However, with a little forethought and a dash of artistic flair, the nengajo phenomenon is a thoroughly delightful and accessible Japanese tradition, and one that serves as a wonderful opportunity to galvanize friendships and professional ties in Japan for the year to come.