I’m sure you’ve heard the target figure: 60 million annual inbound tourists by 2030. Officials have been parroting it for years, and for years observers have questioned whether the target is wise, how the government arrived upon it and how exactly it intends to manage it.

It would be false to say the current administration isn’t aware of the bottlenecks caused by Japan’s tourism boom. It’s well-known that first-timers tend to keep close to the Golden Route, and that small but popular destinations like Hakone, Kamakura, Ine, Yakushima and Naoshima frequently operate at maximum capacity. But knowing a problem exists and forming a coherent strategy to address it are not the same thing.

In 2021, when I interviewed Tadashi Kaneko, who was vice president of the Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO) at the time, he stressed the importance of spreading visitors (and their wealth) across all regions of Japan. It was a message, he said, that had been relayed to the organization’s partner airlines, travel agencies and overseas offices.

I wonder whether this was just lip service or if the message was lost somewhere along the chain of command, because on the face of it, no one has really listened. Here we are in 2024, winter visitors have already hit close to pre-pandemic levels, and as another spring tourism crush is about to descend on the archipelago, we’re hearing tales as old as time.

The Problems With Japan’s Tourism Policy

Tokyo hotel room prices are ballooning. People are wedged, cheek by jowl, along the old walking streets of Nakamise-dori and Sannenzaka. The geisha paparazzi are back in Kyoto, reminding us that humans can indeed be brainless creatures. Locals are being priced out of ski resorts as tourists scramble to experience the fabled “Japow.”

The most popular rural destinations don’t have enough accommodation options to meet the demand, while some hotels are turning away customers as they battle against a crippling labor shortage. These are not the signs of a country that rethought its tourism policy during what was effectively a three-year inbound drought.

And here’s the thing: it was obvious Japan was going to rebound as soon as the borders opened. I’ve had people in the tourism industry tell me they received booking inquiries minutes after the announcement, as though prospective travelers had been waiting at their laptops with their cursors hovering over the “submit” button.

A Lack of Balance

Japan’s popularity has only increased with the recent deluge of online travel news. Readers of Condé Nast Traveler, still one of the world’s most influential travel magazines, rated Japan as the “Best Country in the World” to visit in 2023. The US and Japan, meanwhile, officially declared 2024 as a “Tourism Year” between the two nations.

The fact that Mark Zuckerberg ate at a Japanese McDonald’s and that Taylor Swift had to leave Tokyo to be at an American football match the next day appeared to be newsworthy stories in and of themselves. As far as I can tell, simply including the word “Japan” in a headline makes it eminently more clickable.

But the way in which Japan is often presented — the utter lack of balance — matters too. Vloggers and influencers run around Tokyo recording life in Japan with their 4K-resolution cameras. They suggest “off-beat” itineraries that remain firmly attached to the well-trodden path, regale us with their identical lists of essential tips and the best food to try in Osaka, and romanticize Kyoto like they were the first people to discover it. No wonder tourists follow each other like lemmings around a small chunk of the country.

The idea that Japan needs a more sensible — more sustainable — tourism policy is not new. In 2018, the Japanese government launched its first survey on overtourism in response to increased litter on city streets, commuter congestion, illegal parking and noise levels in rental apartments.

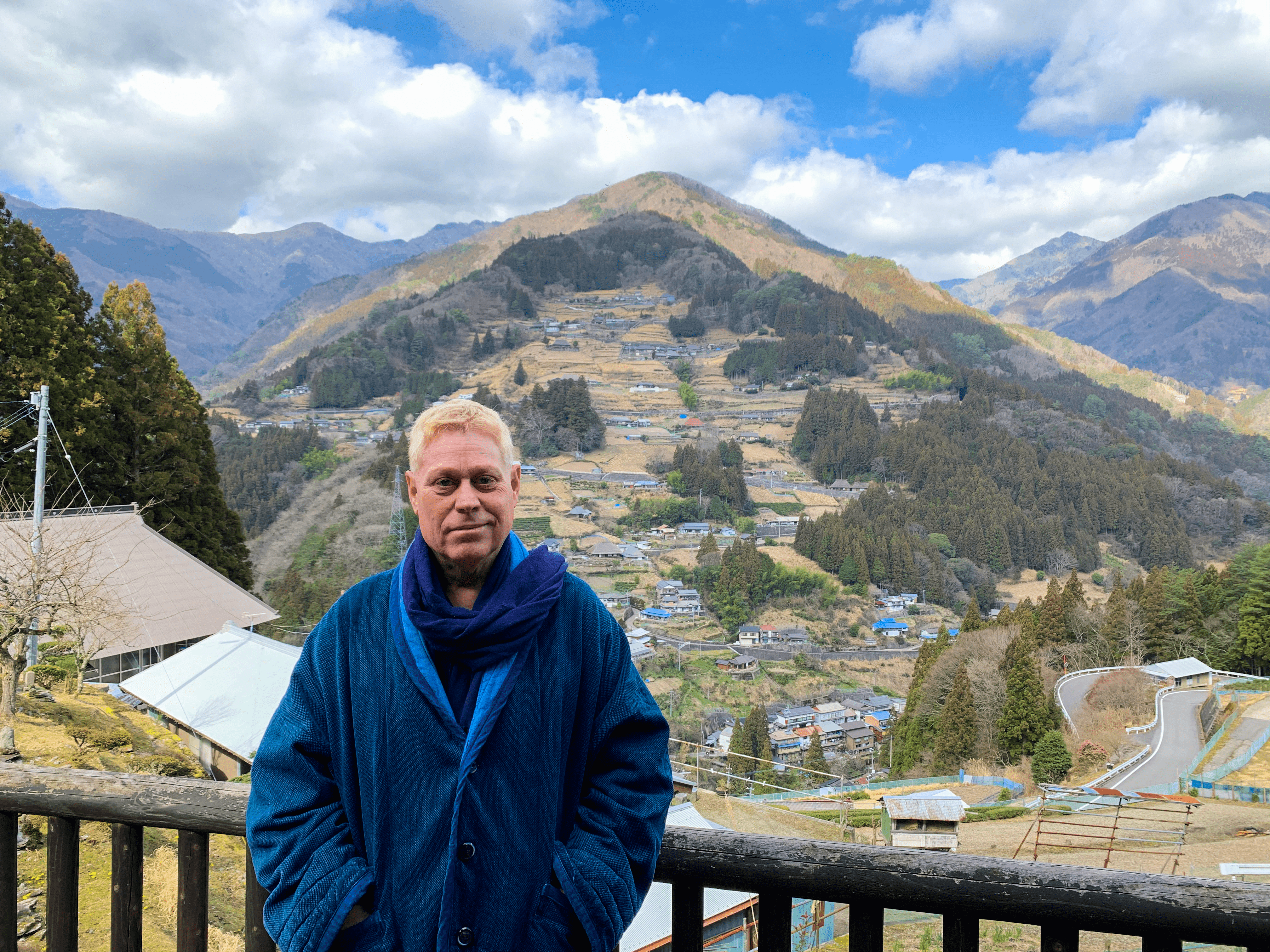

Alex Kerr in Ochiai

The Value of Travel

The following year, longtime Japan resident and author Alex Kerr published (in Japanese) Kanko Bokoku, or “Destroying the Nation Through Tourism,” in which he outlined the consequences of poor tourism management and how an overly egalitarian approach to tourism can detract from the value of experiences.

The second point is worth dwelling on for a moment. What do we really want as travelers? Is the point of travel — of spending significant amounts of money and schlepping halfway across the world — to simply tick a few items off our bucket lists? Even if the intrinsic value of the experience has been completely eroded by crowds and waiting times and endless announcements and signage telling you how to behave? Conversely, if an experience will add genuine value to your life, isn’t it worth paying a little extra?

No one wants to see travel return to the days when it was exclusively the preserve of the wealthy and elite. But asking travelers what the experience is really worth to them, might start deterring the bucket listers. We see it in the Galápagos Islands, Bhutan and Komodo, where pricey tourist charges are commonplace, and in cities across Europe that have hiked up tourist taxes and entrance fees as they brace for the 2024 crush. So why can’t Japan take a similar approach, even if it’s only limited to the most congested areas?

Shibuya

A Conveyor Belt of Visitors

To be fair, local authorities are trialing it at Mount Fuji, hoping to ward off potential Yoshida Trail climbers with the introduction of a compulsory hiking fee. The ¥2,000 total is pretty paltry, especially with the weak yen increasing Western tourists’ purchasing power, but it’s a statement of intent. The number of climbers is to be capped at 4,000 a day, too; a decision that mirrors that of Iriomote, an Okinawan island that now accepts only 1,200 visitors daily. So far, though, such policies are few and far between.

This, though, is not just about cities like Kyoto or famous attractions like Mount Fuji dealing with the conveyor belt of visitors. It’s also about keeping smaller destinations alive. Many rural municipalities, rightly or wrongly, are looking at tourism as the panacea to fix their depopulation-economic woes.

Of course, it would be great if travelers were spread more evenly across the country; if more people explored the rich mythological history of the San’in Coast, realized there were more thatched-roof villages than just Shirakawago, or visited national parks that weren’t Fuji-Hakone-Izu. But it only works if the necessary infrastructure is there to support them, or soon we’ll end up back at square one.

I get that no one wants to be told how to travel. And crafting tourism policy in a high-demand region is an unenviable task. But Japan’s business-as-usual approach is only good for short-term gains and is of no long-term benefit to anyone.