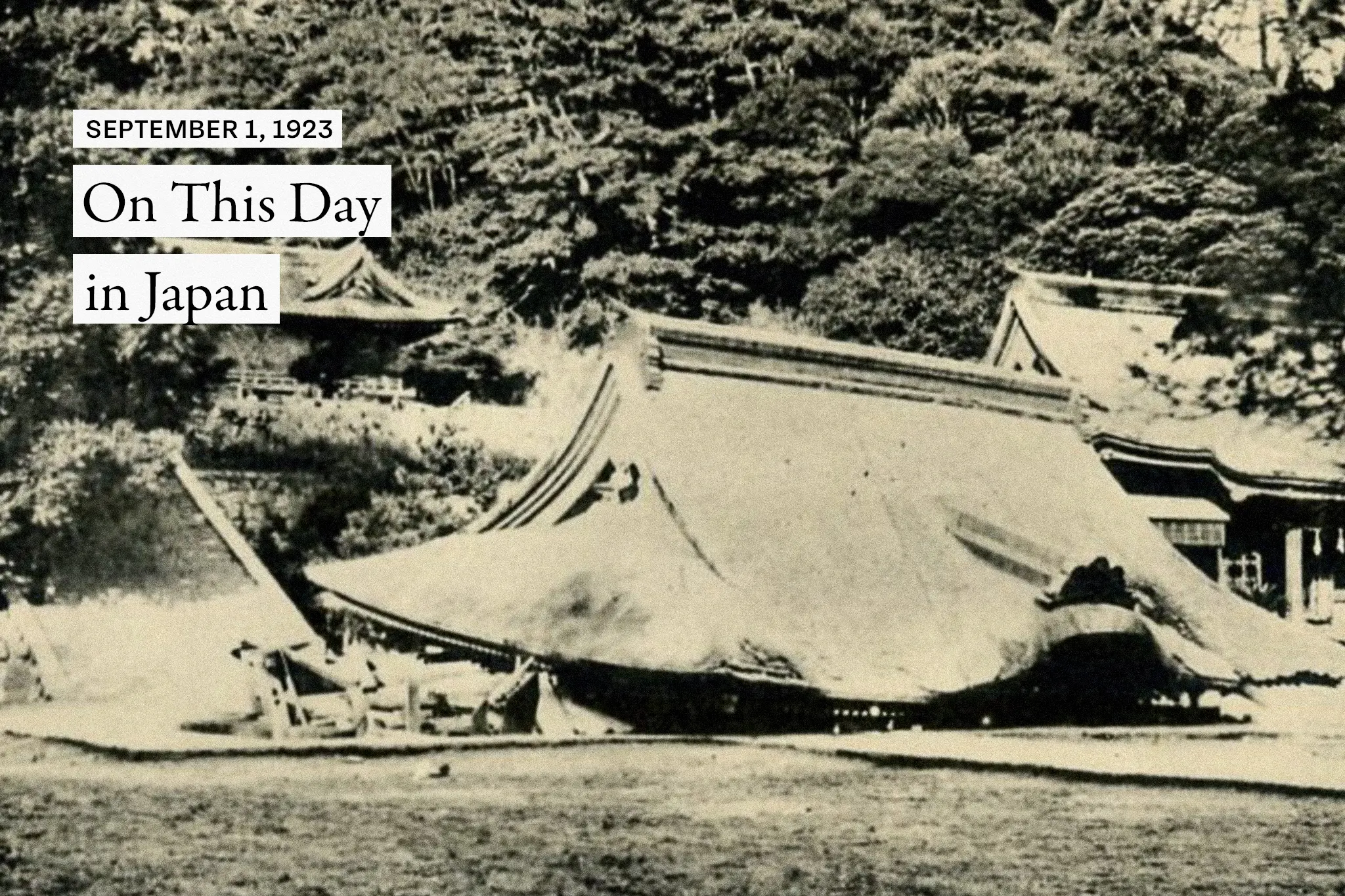

On this day 100 years ago, one of the most destructive natural disasters in recorded history occurred in Japan. The Great Kanto earthquake, which measured 7.9 on the Richter scale, struck Tokyo, Yokohama and surrounding regions just before noon on September 1, 1923.

Over the next three days, there were reportedly almost 2,000 aftershocks. The initial tremor was a few seconds long before being followed by a series of quakes that lasted somewhere between four and 10 minutes, according to varied accounts by survivors. As many people were cooking at the time, fires spread quickly, with some developing into firestorms.

The greatest loss of life occurred on the open ground of the Rikugun Honjo Hifukusho, once called the Army Clothing Depot. Between 38,000 and 44,000 working-class Tokyo residents took shelter there following the quake, but at approximately 4pm in the afternoon, they were surrounded by flames.

A 300-foot “fire tornado” engulfed the area. Only 300 of the people that gathered survived. In total, more than 100,000 people lost their lives due to the Great Kanto earthquake. Some estimates have the figure close to the 150,000-mark. Around 90% of those victims were killed by fire.

Hell on Earth

“It was not long before the place turned into a veritable sea of fire, and one of the most horrible and shocking events ever recorded in the annals of human tragedy followed; hell was indeed let loose on earth.” (The Bureau of Social Affairs, Home Office, Japan).

The force of the quake was so great, it moved Kamakura’s 121-ton Great Buddha statue more than 50 centimeters, despite it being over 60 kilometers from the epicenter in the northwestern part of Sagami Bay. A powerful typhoon also hit the Kanto region around the same time. Winds reached close to 100 kilometers per hour, spreading flames at a terrifying speed.

The earthquake and the heavy rain that followed triggered landslides in the hilly coastal areas of Kanagawa Prefecture and the Boso region of Chiba Prefecture, burying or sweeping away homes and killing hundreds. Huge numbers also died due to the tsunami that struck off Sagami Bay and reached heights of up to 12 meters in Atami.

The tragedy destroyed hundreds of thousands of homes, reportedly rendering around 2 million people homeless, though numbers vary. It also proved devastating from an economic perspective as it destroyed close to 7,000 factories and 121 of Tokyo’s 138 bank head offices. With many hospitals and schools annihilated, Japan’s capital lay in ruins. As did several nearby regions, particularly Yokohama.

The Kanto Massacre

In the panic, wild rumors soon began to spread, including false narratives about escaped Korean prisoners looting, setting fires to houses and poisoning rivers. Zainichi — ethnic Koreans with permanent Japanese residency — were subsequently targeted by baying mobs.

“Partial martial law has already been declared in Tokyo and we request that you increase secret surveillance in all areas and take firm measures in dealing with the activities of Koreans,” was the message from Fumio Goto, the Chief of the Bureau of Police Affairs within the Home Ministry.

Chinese people were also targeted. Vigilantes allegedly tested passersby on how Japanese they were by asking them to recite the country’s national anthem, name all the stops on the Yamanote Line or recall the list of Japanese emperors. Anyone unable to comply or those who mispronounced words were executed.

The Rise of Radical Militarists

They singled out people who looked different. This included the father of famed director Akira Kurosawa because he had a full beard. Writing in his book, Something Like an Autobiography, he said his dad was able to get away after shouting “idiots” in unaccented Japanese.

Several other ethnic Japanese were targeted, including theater director Koreya Senda, who was eventually rescued by someone who recognized him. Two boys from a local deaf school weren’t so fortunate. They allegedly had their throats slit after failing to respond to questioning.

While the government reported that a few hundred, mostly Koreans, were killed in the first few weeks of September, independent reports estimated the number to be approximately 6,000. In his book Yokohama Burning, Joshua Hammer argues that this episode drove the democratic nation of Japan into the hands of radical militarists and ultimately forged the destructive path to World War II.

A Bold Yet Prophetic Prediction

The Great Kanto earthquake and its aftermath was one of the darkest periods in Japanese history, traumatizing and shocking citizens. One person who wouldn’t have been surprised by the tremors, though, was Akitsune Imamura, a seismologist at the University of Tokyo who represented a new generation of scientists that had been trained by Western experts.

In a paper written in 1905, he predicted that a major earthquake would hit the Kanto region within half a century, killing more than 100,000 people. He was subsequently discredited by his senior colleague Fusakichi Omori and accused of scaremongering. After the 1923 quake, however, his popularity grew rapidly.

The Japanese government consequently invested huge amounts in earthquake prediction research. In 1925, the Earthquake Research Institute (ERI) was founded at the University of Tokyo to promote scientific research on topics related to seismology and volcanology and to adopt disaster mitigation measures.

The Aftermath

In terms of reconstruction, the Greater Tokyo area required a gargantuan effort. Some, though, saw it as an opportunity to create a new, modern city. “Now is our best chance to completely remodel and reconstruct Tokyo,” Home Minister Shinpei Goto told his predecessor Rintaro Mizuno. His optimism soon waned, however, due to internal squabbles about how to best spend the money as projected costs far exceeded the national budget.

The scaled-back reconstruction bill was even lower than conservative planners had hoped. Despite this, Tokyo did manage to modernize in the years that followed, building a new network of roads, trains and public services. Significant developments included the first subway line between Asakusa and Ueno, which opened in 1928, and the completion of Haneda Airport three years later.

Today, Tokyo is known for being one of the most advanced cities on the planet. It’s also better prepared for a major earthquake than anywhere else. In refuge parks, for instance, there are charging stations, benches that double up as cooking stoves, manhole covers that turn into emergency toilets and storehouses with enough food for whole districts to survive for 72 hours after a disaster.

Citizens are also well versed in what to do in a catastrophe. Every year on September 1 — the anniversary of the Great Kanto earthquake — millions take part in emergency drills as part of Disaster Prevention Day. It’s needed as an 8 to 9 magnitude megaquake is expected to occur along the Nankai Trough within the next half century. Figures are updated annually, but according to the most recent estimates, there’s a 30% possibility of a quake centered on the trough hitting in the next 10 years and around 90% within 40 years.

More From This Series

Check out other articles from our On This Day in Japan series: