When I look back at Tokyo 2020 — hard to believe it was a full calendar year ago — I’m consistently drawn to the Olympig. A piece of drawing-board conception so tone deaf, not to mention mean, it’s not something one forgets in a hurry. Just to recap, the creative director of the Olympics opening ceremony, Hiroshi Sasaki, suggested comedian Naomi Watanabe, known for pioneering the pochikawaii (“chubby and cute”) movement, abseil from the heavens dressed as a pig: hence, Olympig.

Even a child having this thought would know it’s one they should probably keep quiet about. The fact that it was voiced without sarcasm and came off the back of Tokyo Olympic Committee Chief Yoshiro Mori’s high-profile dismissal — after he let it slip at a press conference that he thought women babbled too much in meetings (ought they not to be refilling the tea?) — is a PR debacle you couldn’t have written.

Rose Vittayaset

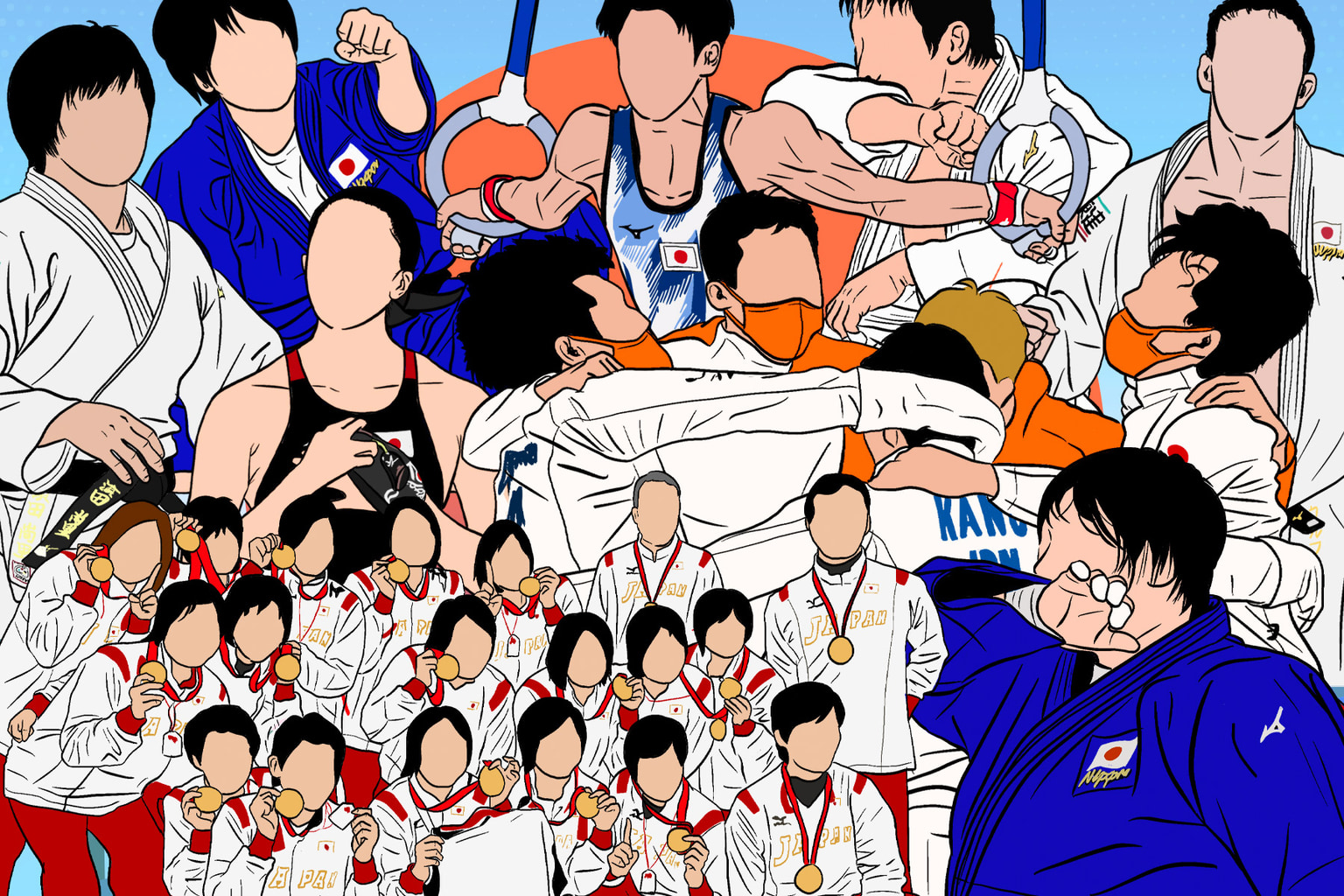

This might not be the most enduring aspect of Tokyo 2020 for everyone. There were, of course, the hundreds of victorious athletes, Team Japan’s record-breaking feats, the few spectators who managed to attend events outside of Tokyo, the Belarusian sprinter, Krystsina Tsimanouskaya, who had to seek exile in Poland after being kidnapped by her coaching staff, or the judoka who escaped the Olympic bubble to meet a mate while concealed in Team Georgia tracksuits. But the mind doth as the mind will.

It is also somewhat relevant, as Tokyo 2020, long before Covid was a twinkle in Wuhan’s eye, was set on portraying Japan as one of the world’s greatest post-industrial superpowers; ready to impress upon its international peers a high standard of living, a new global and inclusive outlook fronted by the “Cool Japan” brand, and a reprisal of the economic boom years which followed its first Olympic Games in 1964.

This is what you may call the “Olympic legacy.” But the Olympig fiasco and a host of other gaffes presaged that perhaps a sporting event was ill-equipped to ameliorate systemic issues in Japanese society.

Rose Vittayaset

What’s In a Legacy?

Sebastian Coe, President of World Athletics and IOC Tokyo 2020 Coordination Committee member, once said that legacy is nine-tenths of what hosting the Olympics is all about.

According to the International Olympic Committee (IOC), “Olympic legacy is the result of a vision. It encompasses all the tangible and intangible long-term benefits initiated or accelerated by the hosting of the Olympic Games/sports events for people, cities/territories and the Olympic Movement.”

This is indicative of the vapid PR speak we became accustomed to over the year leading up to the postponed Games. The IOC presented itself as a benevolent fairy godmother traveling the world and bestowing upon those who need it most the “Olympic Spirit.”

Never mind the lucrative sponsorship deals, the billion-dollar TV rights package, the IOC’s adamance that host cities shoulder all costs as per contractual obligations (causing future host city contracts to be revised), scandals around vote-rigging and under-the-table payouts from sponsors to Tokyo Olympic Committee members, and the ever-evangelizing IOC chief, Thomas Bach, who earns $244,000 per annum for his volunteering efforts.

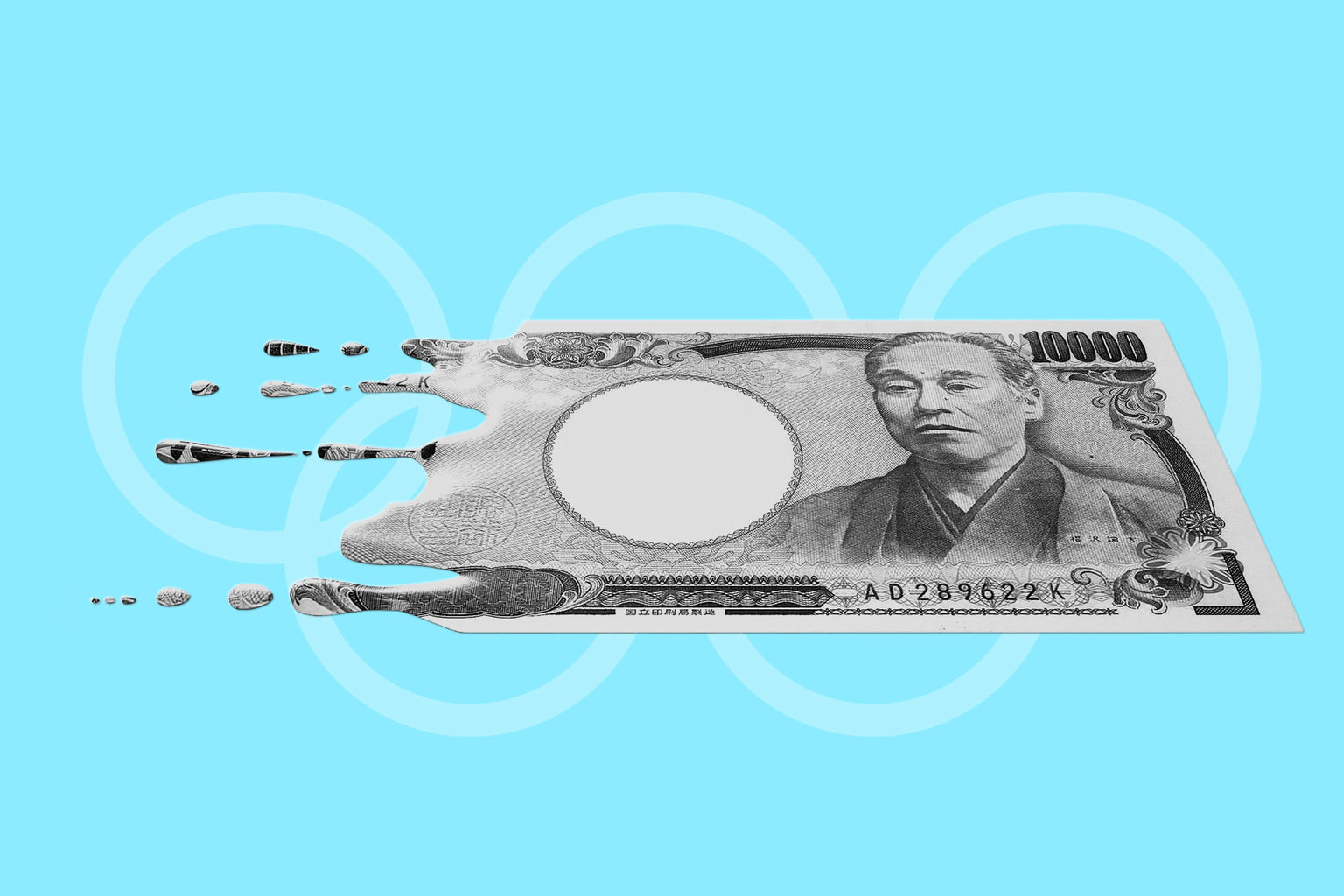

Tokyo was complicit in all this — and paid upwards of $15 billion for the pleasure (making it officially the most expensive summer Games in history) — in pursuit of something Japan has become a master of in the post-war era: soft power.

That’s not to say that profit wasn’t also a motivating factor. When Tokyo bid for the Games in 2013, many of the tenets of Abenomics were folded into the legacy of Tokyo 2020. It was even considered the “fourth arrow” of the late-former PM’s economic policy.

Deflation-prone Japan had predicted a $120 billion-plus economic stimulus and as many as two million jobs created as a result of the Olympics. The postponement and the lack of spectators and international visitors, however, sounded the death knell on such predictions long before the first sprint had been run.

Tourism was, quite rightly, projected to be one of the major economic boosts, with 40 million inbound travelers expected in 2020, alone. But with Japan still closed off to the outside world it’s in danger of losing its relevance in the now-rejuvenated international tourism market. The North Korea-style organized tours, which are the only method for travelers to currently enter Japan, have been a resounding failure. As of late July, Japan — a nation that’s traditionally been tough on asylum seekers — had accepted more refugees than tourists since “reopening.”

In the thrall of the pandemic, Abe’s successor Yoshihide Suga then promised the Games to symbolize humanity’s conquering of the coronavirus. That record Covid cases struck during the Olympics and have now again on its one-year anniversary is a perverse irony, showing the fallen leader — who vacated his post partly because of Japan’s handling of the pandemic during Tokyo 2020 — was as naive as an ill-informed armchair pundit.

The “safe and secure Olympics” moniker felt odd then but feels even odder in retrospect given that the country remains ever masked and is still witnessing over a million new Covid cases weekly. Furthermore, recent research has suggested that a new viral variant was born in the Olympic melting pot with a high likelihood it contributed to further Covid waves in Japan and elsewhere.

Anna Petek

Drowned Out Voices

It’s worth noting that the athletes did put on a thrilling spectacle when they finally arrived. Also, in spite of the setbacks, the Games were organized with Japan’s trademark efficiency — the leaky Covid bubble notwithstanding.

But there are some for whom the struggles cut particularly deep.

Anti-Olympics group Hangorin no Kai, driven by displacement of the homeless and public-housing residents due to Olympics construction projects, were protesting Tokyo 2020 long before such a pastime became a cause célèbre.

For journalistic purposes, I sought out the group to attend one of its protests in the summer of 2021. It was a rather limp affair, truth be told, with as many security in attendance as the few activists howling dissents into the cloying night air. I could see their point, though, asserting that “cleaning up” public land to make way for taxpayer-funded construction projects — including the $1.4-billion Japan National Stadium — was misuse of public finances that could have been better spent.

Hangorin no Kai is representative of anti-Olympics movements across the world, shining a light on the negative knock-on effects typically evaded in official discourse. The benefits of hosting the Olympics have become less apparent, especially in cities that don’t already have the facilities in place. And a year since Tokyo 2020’s completion, the ambitious predictions for its long-term legacy look far from coming to fruition.

Feature image by Anna Petek