by Liane Wakabyashi

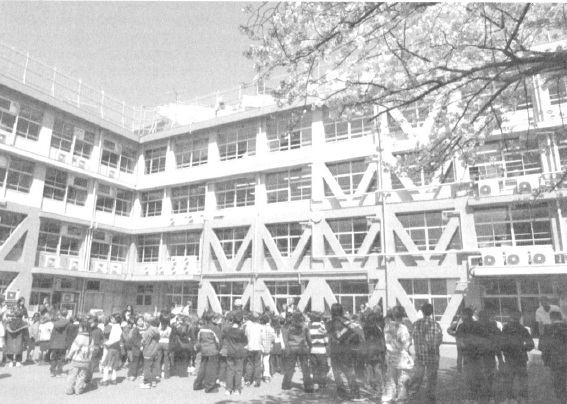

Tokyo International School’s founding director Patrick Newell has in seven short years built upon an awesome vision and commitment to children’s education in Tokyo. After a succession of converted office buildings, first a nursery school, then a primary school, TIS has this month realized a dream of obtaining the former Nankai Elementary School in Mita Ward, a stunningly spacious 1,200 tsubo campus 500 meters down the road from TIS’s former facility.

Newell believes “things come from synchronicity.” But longtime friend and TIS administrator Mayumi Murata says Newell is “really positive.”

She continues: “It’s his way of thinking that’s behind TIS’s growth in such a short time. But if it was only coming from a business perspective, it wouldn’t be the same. Patrick’s heart is really into education.”

TIS is one of several education-related businesses run by Newell and his wife Ikuko Newell-Tsuboya, or Bea, as she likes to go by. Children’s House, a pre-school classroom of 12 children begun by the Newells in September 1994, was renamed TIS in 1997 when the school expanded to become an international elementary school for bi-cultural children such as the Newells’ two daughters, Maya (11) and Kana(10).

Today the TIS population has grown to 250 students, representing children from 35 countries. Rapid growth required that TIS make frequent moves. Since 2000, the campus has been in Mita, near the expatriate residential community and what the Newells discovered to be an empty elementary school literally in their backyard.

It was a four-story property with an outdoor swimming pool, running track and secluded off-road entryways. Step by step, TIS positioned itself to prove it would be a model tenant. For the two years prior to winning approval for full occupancy, TIS was able to lease the all-wood gymnasium for its classes. TIS had struck up relationships with five other Japanese elementary schools, doing art projects, sports activities and language exchanges.

Collaboration with the local Minato Ward branch of UNESCO is now in its second year, with the annual TIS charity concert raising funds for UNESCO.

When the destiny of Nankai Elementary School was handed to TIS, a major renovation project was undertaken, with Minato Ward ensuring the school is in line with the latest earthquake-proof codes.

Newell brings a sensitivity to aesthetics unheard of in Kyoiku Inkai (Japanese Board of Education) circles and has gone about his renovations with delicacy, diplomacy and a fair amount of humor.

The drab beige elementary school facade has been repainted in shades of blue, yellow and orange. The white metal entry gate has been reconstructed in solid wood, “to give a warm, secure feeling that also has a sense of Japanese tranquility.”

“I can’t wait to see their (the board members’) faces when they finally enter this building.” Newell smiles with a charming, boyish grin.

Inside, the school is now thoroughly Western, with state-of-the-art technology — three mobile wireless computer labs containing 70 laptops and 40 desktops, a spacious library containing thousands of volumes and a frontal view of a 25-meter swimming pool.

The rows of shoeboxes in the entrance hall have been removed to make room for another of Newell’s concepts: a European-style living room, with comfortable sofas and a cafe for TIS parents and staff to enjoy. According to Newell, the colorful salmon, blue, rose and yellow hallways on each floor are “designed to alternately calm and energize” children of all ages.

The decor of the toilets will be based around themes of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. For those more philosophical moments, quotations placed on the steps leading to each floor and around the school by TIS parent Aileen Emerling will give children — and teachers, parents and administrators — pause to think.

In the six years Darren Laverick has known Newell, the former TIS first grade teacher and now school principal says he is continually amazed by the strength of Newell’s vision and his drive to see it through.

“Patrick is recognized as an education specialist worldwide. He is involved in participating in accreditation teams at other international schools around the world, writing a dissertation for a Masters in International Education and acting as an educational advisor.

“It’s not difficult to be inspired by him,” adds Laverick. “His knowledge of education and research on how we learn is so vast, he is able to discuss deep issues with real understanding. He also has a very practical side and has even been prepared to step in and help set up furniture in classrooms or substitute-teach. He really cares and is always willing to put himself out.”

TIS serves mostly foreign expat families of short duration (the average stay of its students is three years) who require that the TIS curriculum transfers fully to any English-speaking setting in the world. TIS is in the process of adopting the International Baccalaureate Primary Years Program (IBPYP) which, according to Vice Principal Lance Kelly, is the fastest growing international school curriculum in the world.

“The beauty of the IBPYP is that it isn’t locked into a national curriculum. TIS’s mission statement — ‘To nurture confident, open-minded, independently thinking inquirers for global responsibility’ — could have been plucked right from IBPYP, but in fact these were Patrick’s words. So when IBPYP came along, it was a natural marriage.”

IBPYP schools use a methodology called inquiry-based learning. The school year is broken down into six units of inquiry, lasting six to eight weeks. Each unit is connected to a central idea or question, which becomes the starting point for children to go off to explore and demonstrate their understanding in a wide range of ways.

“In kindergarten, at least a couple of hours is devoted to reading activities and some form of writing every day,” explains Kindergarten teacher Kim Jones. “Our current unit of inquiry is ‘ From Field to Table,’ in which all learning relates to how food is produced. Learning is reinforced by the ‘Word Wall’ — posters containing reading strategies and components of a story, the library shelves and a cross-age buddy system with fifth graders.

“In broadest terms this methodology is known as differentiated teaching,” explains Kelly. “Teachers work out what they want the children to learn, then give different assessment tasks to show if the objectives have been met.”

Emerling praises TIS’s child-centered focus. “The kids are encouraged to think about ‘how to think,’ instead of just rote memorization of spit-back facts with no relevance outside the math quiz or social studies questions.”

Until recently, TIS teachers used small rooms and space to the best of their abilities. Everything is now more spread out at the new campus, and with it come novelties Japanese children take as their birthright. Students will enjoy large windows, wide halls, spacious classrooms, science labs, art and music rooms, a gymnasium and playgrounds.

Although it may take some adjustment to learn to navigate long corridors and staircases connecting facilities they never had before, such as the rooftop playground and the gymnasium for example, no one is complaining.

The two entrances to the new campus are approached by private pathways which will provide a zone of safety and comfort for the TIS community. At the same time, Newell sees his new campus as a bridge to collaborating with the Japanese community.

“I have really enjoyed designing our new campus. Almost every day I have been on the construction site collaborating with various companies, choosing materials and designing ‘feelings’ in different areas of the building to create an environment conducive to learning which projects a positive feeling.”

Ikuko “Bea” Newell-Tsuboya

“Patrick is the ideas man, he has the dreams — I support on the practical side,” explains Ikuko Newell-Tsuboya.

However, Tsuboya-Newell’s forte is indispensable to the success of TIS. She’s a persistent negotiator and has been a key player in the TIS move to the former Nankai Elementary School premises. The Newells, with their right-hand man, business manager Shiga Otsu, approached government officials, reviewed contracts and handled the financial side.

“In this society, it’s stressful if you’re trying to do something that hasn’t been done before. It’s tough,” she says.

When they finally won the approval of the local and national government bodies they had courted for three years, Tsuboya-Newell called a key government official to thank him for all the help he gave.

The official retorted: “I realized you are shitsukoi — you were never going to give up!”

“If it wasn’t for Bea and Otsu’s continuous belief and dedication towards creating the best environment for the TIS children, our move would have been nearly impossible,” her husband adds.

Tsuboya-Newell has been involved in education since 1985, when she opened her first English school called English Studio, and she went on to write a book on educating parents, Eigo no Dekiru Kodomo wo Sodateru, on how to teach English to their children, published in Japanese by Kodansha.

As for the future, Tsuboya-Newell is turning her attention to overcoming what she sees as the next hurdle: getting gakko hojinkaku (official school) status. For that, a school needs its own land to establish a permanent address. “It may happen that we stay a long time at the new address. My job is to help ensure we will have a back-up plan.”

Testimonial of a parent

Aileen Emerling, mother of two boys, Thomas and Ryan who attend TIS, says: “We are in our fifth year at TIS. I volunteer each week in my son’s Grade 2 classroom where they are currently learning about dinosaurs. The learning comes in lots of different forms, from building models, understanding sizes and graphs, to learning history, sharing the information with the class and writing reports.

“So within that unit of inquiry, all of the core disciplines of learning are touched upon. For the teachers to design and use these kinds of units, lots of work and thought goes on behind the scenes.

“When you see how the kids are working during those units, you see the math and science coming alive to them in a way that has value and meaning. And I believe that, when you give children a project that has value to them, they will put themselves into it more readily.”When you see how the kids are working during those units, you see the math and science coming alive to them in a way that has value and meaning. And I believe that, when you give children a project that has value to them, they will put themselves into it more readily.

External Link:

Tokyo International School

Updated On July 17, 2013