A name is never just a name. It’s a claim, a narrative, a declaration of power.

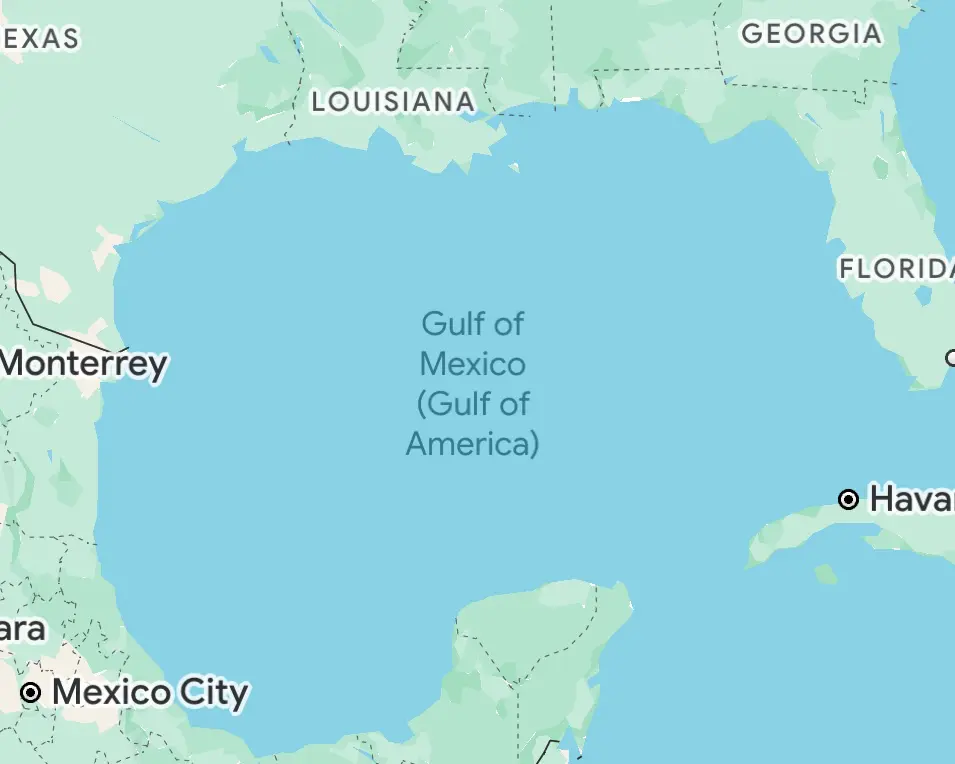

In a move that has ignited international debate, President Donald Trump has issued an executive order renaming the Gulf of Mexico the “Gulf of America” — at least within US federal documents and maps. A purely symbolic move? Maybe. But symbols matter.

Google Maps has confirmed it will implement the change for US users while keeping the original name for international audiences.

This, though, isn’t the first time cartography has been rewritten due to politics.

The ‘Gulf of Mexico’ vs. ‘Gulf of America’ Dispute

Borders shift. Empires collapse. Names get rewritten. The Gulf of Mexico — now Trump’s so-called Gulf of America — has been a geopolitical fault line for centuries. The US shares its coastline with Mexico and Cuba, two nations with which it has long had complicated relationships.

The gulf itself is a lifeline, an economic artery critical to trade, oil production and military strategy. It was through these waters that Spanish conquistadors arrived, that European empires clashed, that America’s own expansionist ambitions took root. The Monroe Doctrine, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the BP oil spill — history drifts in these tides.

And now, the name changes.

Renaming the gulf may not redraw maritime borders, but it feeds into a larger narrative of American dominance. It’s a flex. A rebranding exercise for a presidency built on nationalist spectacle. Mexico — America’s southern neighbor, often the rhetorical punching bag of the Trump administration — was quick to push back, with President Claudia Sheinbaum sending a letter to Google contesting the name change and reminding the tech giant that a country’s sovereignty extends but 12 nautical miles from its coastline. Beyond that zone, she noted, is international waters, which only international organizations have the authority to rename. Sheinbaum also took a jab at Trump’s rebranding, reviving a 1607 map labeling parts of North America as “Mexican America” and jokingly suggesting Google display it in searches.

Meanwhile, across the Pacific, another naming dispute continues to brew.

The ‘Sea of Japan’ vs. ‘East Sea’ Dispute

For nearly a century, the name of the marginal sea separating Japan and the Korean Peninsula has been a geopolitical flashpoint. The dispute is more than semantics — it reflects deeper tensions between Japan and South Korea, shaped by historical grievances and national identity.

The term “Sea of Japan” gained international recognition in the 19th century, coinciding with Japan’s rise as a regional power during the Meiji era (1868–1912). By 1929, the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) had officially recorded “Japan Sea” in its Limits of Oceans and Seas, reinforcing the use of the Japan-centric term in global cartography. South Korea, however, argues that this name was determined during Japan’s colonial rule over Korea, a period when Korea lacked diplomatic agency to challenge such designations. In its assertion that “East Sea” deserves recognition, the South Korean government points to historical records, claiming that references to the “East Sea” (or “Sea of Korea”) date back to the 17th and 18th centuries on European maps and even earlier in Korean records.

Since the 1990s, South Korea has sought international recognition of “East Sea,” or at least dual labeling, presenting its case at UN and IHO conferences. In 1992, Seoul formally raised the issue at the UN Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names. Japan, however, insists that “Sea of Japan” was widely used long before colonial rule and maintains that the IHO’s early designation reflected established global cartographic practices.

The diplomatic battle has spilled over into state lobbying and domestic politics. South Korea has lobbied map publishers and tech companies, including Google, to adopt “East Sea” alongside “Sea of Japan” in South Korean territories, while Japanese officials have lobbied against changes in international forums.

In an attempt to defuse tensions, the IHO in 2020 adopted a neutral approach: a “numerical system” to designate the sea instead of a name. The shift, finalized during a virtual IHO session, was celebrated by South Korea as a partial victory, though Japan downplayed the significance of the decision, emphasizing that “Sea of Japan” remains in official printed editions.

Google Maps has taken a diplomatic approach: labeling the sea as “East Sea” within South Korea while maintaining “Sea of Japan” internationally. In some countries like Poland and New Zealand, users have reported seeing both names displayed simultaneously.

Maps as Political Weapons

Cartography has never been neutral. Place names tell stories, and those stories are written by the victors.

Denali vs. Mount McKinley. Burma vs. Myanmar. The Falklands vs. Las Malvinas. The Persian Gulf vs. the Arabian Gulf. Each name carries baggage — colonial histories, nationalist pride, geopolitical ambition.

A name won’t change geography, but it can change perception. In politics, that’s often enough.