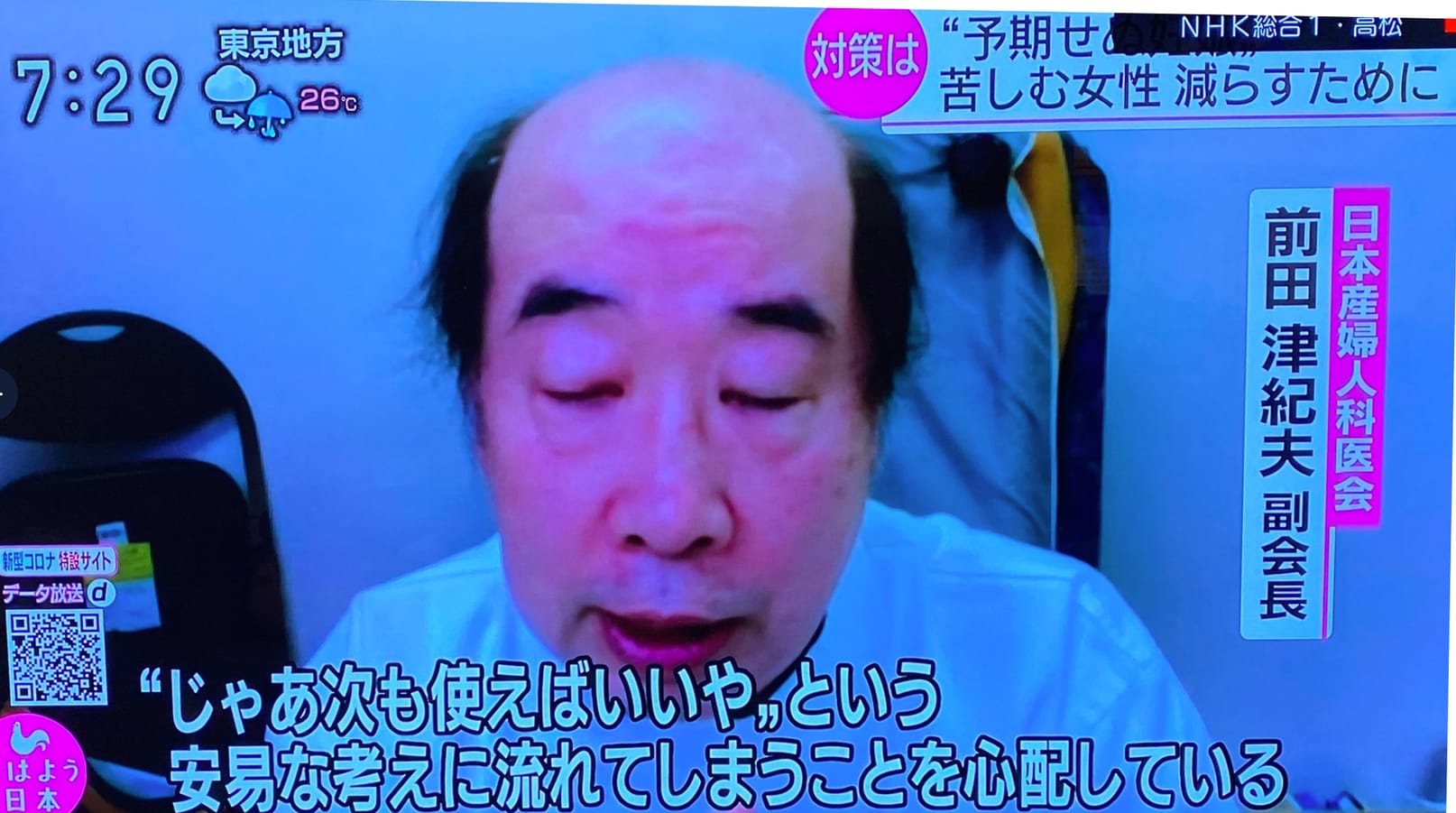

On the morning of July 29th, the vice president of the Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (JAOG) vocalized his doubts about making the Emergency Contraceptive Pill (EC, aka the morning after pill) more accessible for women in Japan on NHK’s “Ohayo Nippon” by stating, “If we make the morning after pill more accessible, I’m worried that young women will think, ‘Oh, I can just use it again next time’ and not take it seriously.”

This isn’t the first time in history that Japan’s medical professionals have delayed women’s access to oral contraceptives. They didn’t become legal in the country until 1999, decades after already available, and only after the legalization of viagra. The vice president’s comments were made in resistance to the ongoing movement to create pharmaceutical, over the counter access for emergency contraception pills in Japan. The EC pill is currently only available after making an appointment at a clinic, consulting with a doctor, getting a prescription and paying upwards of ¥10,000.

The vice president’s comments shocked and angered women across Japan.

A screenshot of the NHK program in which the vice-president of the Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (JAOG) Mr. Maeda, raised his concerns over a potential misuse of the morning after-pill if made easily available.

Shortly after the show was broadcasted, women in Japan took to social media to express their frustration with the remarks given by a representative who is supposed to function as a pioneer for women’s wellbeing. Hashtags like nandenaino (#なんでないの, Why don’t we have it? ), kinkyuhininyakuwoyakkyokude (#緊急避妊薬を薬局で, EC at the pharmacy) and after pill (#アフターピル, the morning after pill) began trending on Twitter.

Aya, 26, creator of Ko Archives, a platform designed to connect and celebrate Japanese women’s visibility, shares how she felt when she first read the news on Twitter. “I was horrified. I think his statement was totally unacceptable for someone of his position. This is supposed to be a medical professional — someone who is considered an expert. So even if he says something that’s just speculation, people might take it as fact. And I think that’s really dangerous. This was something I’d expect a conservative politician to say, not a medical professional.”

“The Emergency Contraceptive pill is currently only available after making an appointment at a clinic, consulting with a doctor, getting a prescription and paying upwards of ¥10,000.”

Akiko, 43, mother of two, an office worker in Tokyo, says decidedly, “He can’t understand women’s health because he is not a woman.”

Chika, 28, an office worker in Tokyo, says, “My first response was, ‘Why is he only targeting women?’ It sounds like this issue is blaming women. The choice women/men decide to make when they have sex is not a one-sided decision. Also, sometimes there are some circumstances where [women] are forced to [have sex] without using a condom.”

Keiko, 41, a mother of four, said of the vice president’s comments that “it’s an old fashioned way of thinking.”

Akiko, an office worker in Tokyo, says, “I think the remarks from the Vice President of JAOG were very negligent. It seems that he wants to punish women who have sex and don’t want pregnancies by not giving [easy access to pill].”

“It’s not like eating candy,” says Margherita, 24, a hospitality worker from Italy currently living in Tokyo.

In a bid to address those voices officially, two organizations, #nandenaino (Why don’t we have it) started by Kazuko Fukuda and NPO Pilcon founded by Asuka Someya, began speaking up. On July 21st, they submitted a Citizens Initiative letter to the Minister of Health, Labor and Welfare requesting over-the-counter access to EC and a safer system that better meets women’s needs. The request emphasizes the heightened demand for EC due to the pandemic, where Covid-19 restrictions and anxieties have further impeded women’s access to sexual healthcare in a time when it’s most needed.

Out of reach: An emergency pill that isn’t readily available for emergencies

Far from the vice president’s expressed concerns about “haphazard use” is the reality of this medicine’s purpose. The Emergency Contraceptive pill, akin to its name, was designed for precisely just that: emergencies. The pill prevents the sperm and egg from meeting by delaying ovulation and stopping fertilization from even beginning to occur. Naturally, this makes the pill most effective when taken almost immediately after intercourse, or in the case of Norlevo (the only brand Japan has in stock), within a window of 72 hours. When made available, the pill can prevent unwanted pregnancies for women who have had sex without adequate protection, and women who have been sexually assaulted.

“For many women in Japan, the high prices of emergency contraceptives, the absence of many hospitals on weekends and at night and the obstruction of obstetrics and gynecology hinders their visits,” says Asuka Someya, chairperson of Pilcon. “I think the issue is that conservative men with power neglect the importance of SRHR (sexual reproductive health and rights),” says Someya. “In Japan, sexual matters have long been a taboo and has not been discussed or emphasized in public. As the WHO advocates, contraception is essential, and in the Covid-19 pandemic, it is a natural right for all women to have access to contraception.”

“Those who don’t have access to the EC pill are forced to endure the possibility of becoming pregnant and giving birth or choosing to have an abortion”

Those who do not have access to the emergency contraceptive pill are forced to endure the possibility of becoming pregnant and giving birth or choosing to have an abortion, which in Japan can cost anywhere between ¥80,000 to ¥550,000 include your male partner’s signature on a permission form. Victims of sexual assault can receive financial support for EC, but only 3.7% of victims go to the police due to Japan’s limited definition of rape and an environment that runs rampant with victim-blaming as seen in the case of Shiori Ito.

“I feel they don’t understand how serious and how hard [it is] for a woman to face the fear of unintended pregnancy,” says Fukuda from #nandenaino. “And it’s really sad that such people who really, really don’t understand the core feelings of women are in such a top place of managing women’s health in Japanese society.”

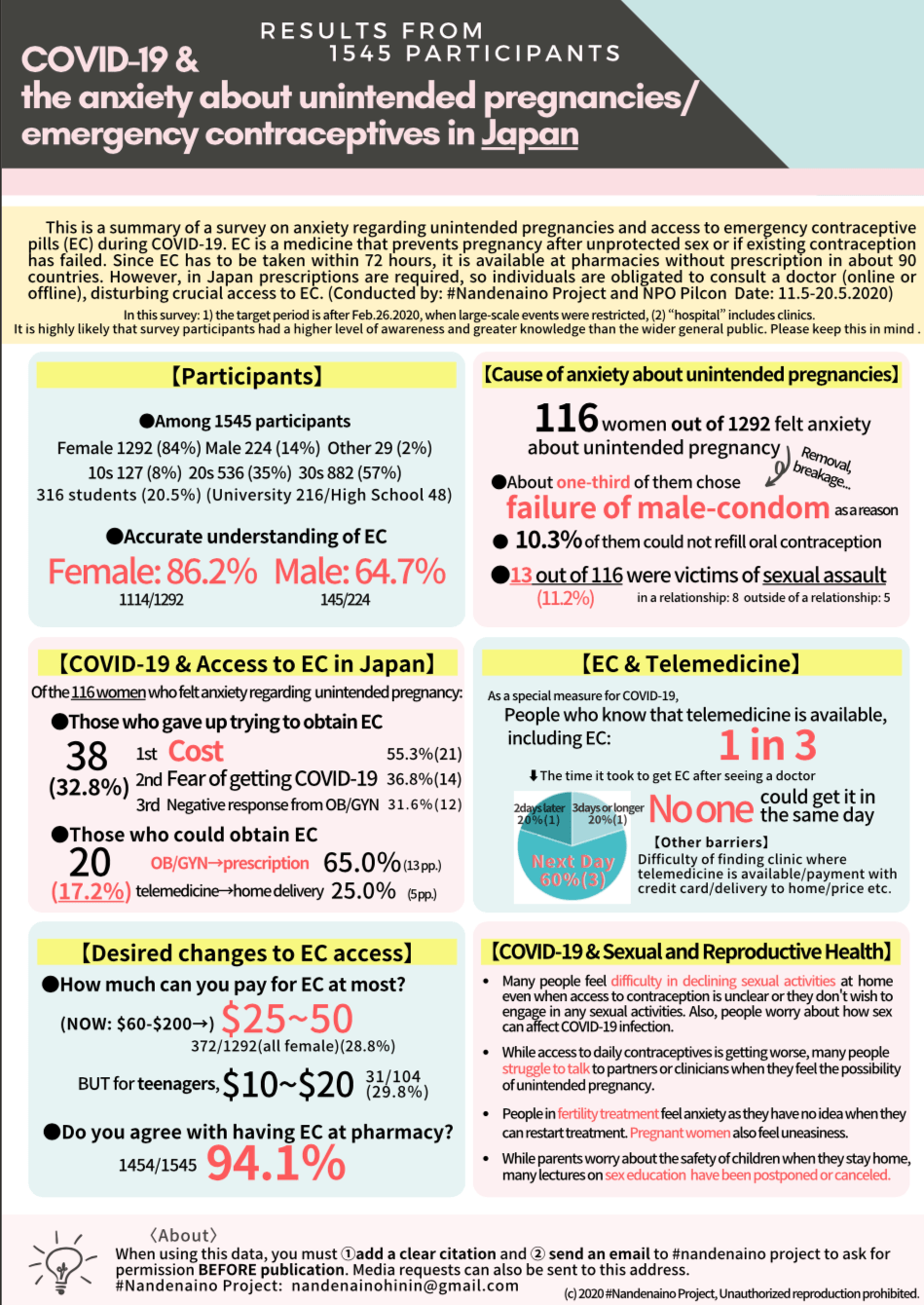

In a recent survey conducted in May of 2020 by Pilcon and #nandenaino, 94.1% of women agreed that the emergency contraceptive should be made available at pharmacies. The main reason women gave up trying to get oral contraception was the expense. The second reason was the fear of getting Covid-19. Someya says the third primary reason for giving up is the fear of getting an adverse reaction from the gynecologist.

Image courtesy of #nandenaino and Kazuko Fukuda

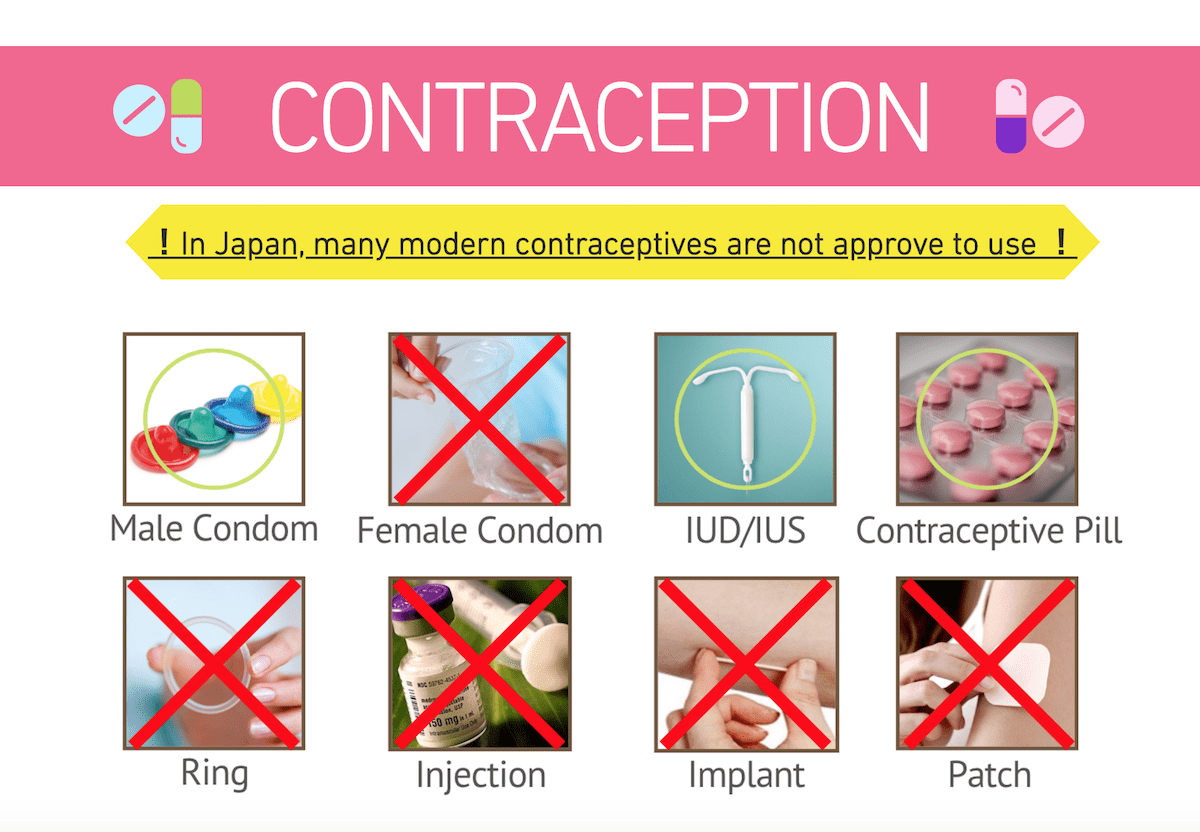

Limited sexual health education and lack of contraceptive options

Japan ranks 121st in gender equality out of 155 countries. As a country rather infamous for its overtly sexualized sensibilities, there lingers an insidious irony in the lack of sexual health education and protection. According to research at Pilcon and #nandenaino, 82% of people having sex in Japan use condoms as their primary method of contraception, and just 4% of women use other contraception options such as the pill or an IUD. Other forms of contraception are not available in Japan and many doctors are unfamiliar with them. Condoms, which have a failure rate of about 20%, can break or be misused, and yet there still remains resistance from medical professionals, evading accessibility to an emergency pill that they’re paradoxically creating a higher need for.

Noriko, 45, a mother living in Tokyo, relates that she learned about reproduction through a rather shocked childhood friend at ten years old. “I was never taught about sexual interaction, I think it depends on the generation. [I read] there was a program to teach sexual education in Japan, but the conservative politicians turned it down.” Noriko says she hopes Japan improves sexual education policies. “I think both girls and boys need appropriate sex ed [in order] to respect our bodies. Especially boys.”

Similarly, Yoko, a college professor in her 40’s, shares the single sexual health orientation experience she had in elementary school. “I watched a video about periods with male students when I was about 10 years old. A male teacher showed us the video and he explained nothing because he didn’t have any experiences [with that].”

Image courtesy of #nandenaino Project

Yukiko, 36, a clinician, describes her experience in equally underwhelming terms, lamenting the lack of information she was given both in school and as an adult. “Condoms are the main resource for contraceptives for me too. I was not familiar with getting the doctors’ pills because we can buy condoms at the stores easily. It’s all about accessibility.”

Margherita, 24, from Italy, was disappointed after her first visit to a clinic in Japan. “The whole gynecologist world [in Japan] is very ‘old.’ I was using the nuvaring and I had to switch back to the pill because [the nuvaring] doesn’t exist in Japan and you can’t get a prescription. I printed some things off the internet before going to the clinic and basically, I had to explain to the doctor what it was and how it works.” Other international residents in Japan attest that some clinics didn’t provide the option of using an IUD until recently.

An environment that fosters taboo and shame

Perhaps one of the most pervasive factors eroding women’s health and safety is the constructed social stigma and shame of having sex. “Lots of Japanese men still desire sexual purity [in] women. It’s the time to change such an old stereotype thought,” says Akiko. With comments like the vice president of JAOG being made on national television, it’s easy to comprehend the extent of the harm done by the backward assumptions placed on womens’ shoulders and the negative impact it has on health and safety.

“[It’s] the culture of shame (Haji). Being informed and educated about anything sexual, or being open about those things, somehow, makes you look ‘slutty.’ And that, traditionally, makes you undesirable as a long term partner, or a wife.” Says Ayumi Melody, a musician and English teacher from the UK and Japan. Having had to take the pill twice in her early twenties while living in England, Ayumi reflects on a “hard and messy time.” “Not everyone can think rationally and clearly all the time, not everyone feels comfortable going to the doctors for these things. Adding a more accessible option will never harm anyone, it will only help us. So I feel on a very personal level that this is an extremely important issue.”

Megan, 26, shares a personal story where she had to take the morning after pill while living abroad in Japan. A friend accompanied her to the clinic and translated some doctor requests that she didn’t expect. “We got into a room and I had to undress and have him look up my vagina. In retrospect, it was a violating procedure and clearly intended to act as a barrier and discourage women from seeking out emergency contraceptives. In the doctor’s many questions, he always referred to the fact that I was worried about the condom breaking as ‘my mistake’.”

Upon returning home that Christmas, Megan bought the morning after pill to bring back to Japan just in case. “I never had to use it. But it was a comfort to me that if something should happen again, I was prepared and wouldn’t have to go through the same ordeal. I know that for the vast majority of women in Japan, this is not possible.”

In one of her closing statements, Someya reiterates the importance of facts and medical needs when battling ideology in Japan. “[It should be viewed] from the perspective of public health and evidence, rather than moral theory.”

A movement that drives forward despite pushbacks

In 2017, although 320 out of 380 public comments showed “positive responses” toward making EC available at pharmacies, the motion to do so was shut down by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, citing “hazardous use” as one of their main concerns. But the fact remains that the public, especially its women compatriots, are eager for change.

Most recently, the Parliamentary Vice-Minister for Health, Labor and Welfare positively received the Citizens Initiative request submitted by Pilcon and #nandenaino this summer, but a specific deadline to respond has not yet been mentioned. Educators like Someya and Fukuda are actively continuing the dialogue with OB-GYN groups in Japan, and fighting for their human health rights.

Fukuda reflects on the sheer amount of positive comments and support they’ve received since beginning the petition in September of 2018. She remembers one recent critique regarding the name of her project “nandenaino.” Why are you using a negative phrase? It criticizes others. Why don’t you use a positive one, like “attaraiina” (It would be nice if we had that). “I understood what they were saying,” says Fukuda, “but I believe that what I demand is not something better to have; it’s something essential.” There’s momentum and understanding in her voice when she says. “It’s something necessary, not additional.”

This article was born after several interviews with women in Japan: leaders at the front of the political hearings to make emergency contraceptives more accessible, those with personal experiences of the Japanese sexual health care system, and those who are actively observing and learning from the sidelines. Some names have been changed or omitted for privacy reasons. All interviews have been condensed and edited for clarity.